Looking back at the 40th anniversary of punk in 2016 through interviews with members of the Damned and Buzzcocks, and a rundown of main events, such as the son of the Sex Pistols’ former manager burning some US$7 million of punk memorabilia.

By Jim Algie

To all the detractors and naysayers whose cries of outrage grew into a choir of hostile disapproval in 1976, punk rock was but a passing fad that would only last six months to a year.

Forty years later, two of England’s cornerstones of the genre, the Damned and Buzzcocks, embarked on anniversary tours that are continuing in 2017, a major exhibition of the Ramones’ instruments, T-shirts and posters showed at museums in New York and Los Angeles, while the son of the former Sex Pistols’ manager cremated millions of dollars’ worth of punk memorabilia. The burning was even listed as one of the events slated for Punk London, a yearlong series of exhibitions and film screenings supported by (irony alert) the Mayor’s Office of London.

All these events beg the question: How did such a pariah genre become a respectable bastion of pop culture?

For Captain Sensible, the guitarist of the Damned, it’s all about honesty. “Punk is honest music. No choreography, no million-dollar production jobs, no phony lyrics,” he says over the phone from England.

When the debut albums by the Ramones and the Damned came out in 1976, rock music had strayed so far from its origins of two-minute, three-chord songs by Elvis, Eddie Cochrane and Chuck Berry, that it was languishing in a cloud cuckoo land of fairies and demons riding stairways to heaven and highways to hell. Single songs took up entire sides of albums. Prog-rock bands toured with symphony orchestras, while laser light shows and other theatrical props upstaged many headlining acts at concerts (not gigs, not shows, but rock concerts) held in arenas built for sporting events not bands.

A recent pic of Captain Sensible of the Damned Photo credit: Wikimedia commons

Many of the early punk groups, though notably different in sound and style, were united in their contempt for the bombastic music of these brontosauruses and their overblown shows. “The UK bands all had their own sound, their own take on what punk was about,” says Captain Sensible. “The Stranglers sounded nothing like the Buzzcocks who were in turn quite different to the Clash. We all agreed on one thing though and that was the old dinosaur acts like ELP and Yes were past their sell by date and they could take their 20-minute drum solos and songs about wizards and pixies and fuck right off.”

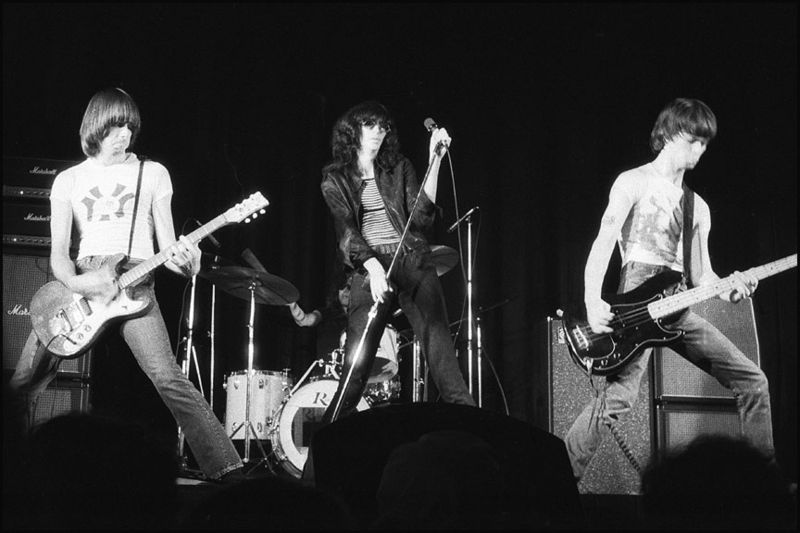

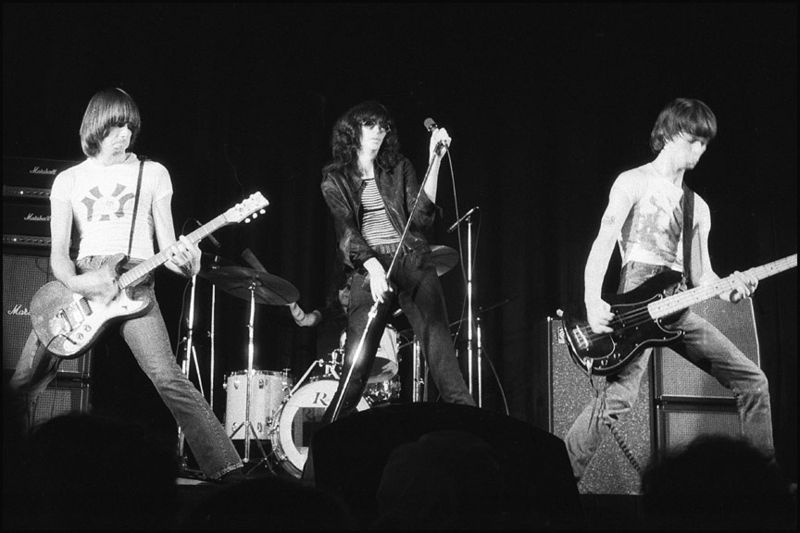

All revolutions have landmark dates and anniversaries when the scattered forces and brewing storms that are charging the air find a weathervane to ground and guide the movement. On July 4, 1976, the 200th anniversary of the signing of the American Declaration of Independence, the Ramones rallied the shock troops of young British punks when they played London for the first time. By many accounts, including the leader of the Clash, Joe Strummer, in his last ever interview, for the Ramones documentary End of the Century, and the group’s manager, Danny Fields, who had previously worked with the Doors, the Stooges and the MC5, this was the show that galvanized the British scene. In the documentary, Strummer fondly recounted how the Ramones formed a human chain to pull the members of the Clash up into their dressing room on the second floor, and how the band was so tight that even the skeptics stood in silence and awe.

The Ramones’ short and sharp stabs of distorted speed-pop cut through the flab of prog-rock like a chainsaw, as they brought rock music down from the clouds and put it back on the streets again with odes to sniffing glue, beating up brats, horror movies and male prostitutes turning tricks on “53rd and 3rd,” played by a bunch of scruffy-looking guys dressed in leather jackets, T-shirts, jeans and sneakers, who looked more like a street gang than a rock band, so that one piece of punk-lore (perhaps apocryphal) has it that the owner of CBGB, Hilly Krystal, quickly offered them their first gig after they asked about playing there, because he’d first thought they had shown up to rob the place.

Captain Sensible was also at the Roundhouse in London on that momentous night in 1976, along with the future vanguard of British punk. He describes the gig as “a spectacular fusing of wall of noise, garage and pop music. And Joey was a lovely bloke.”

The show came only a month after the infamous Sex Pistols’ gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester, where future members of Joy Division, the Smiths, the Buzzcocks and the Fall were in attendance. That show inspired the 2006 book by David Nolan called I Swear I Was There: The Gig that Changed the World, and would be restaged in the films 24 Hour Party People and Control, the biopic of the late Joy Division singer Ian Curtis.

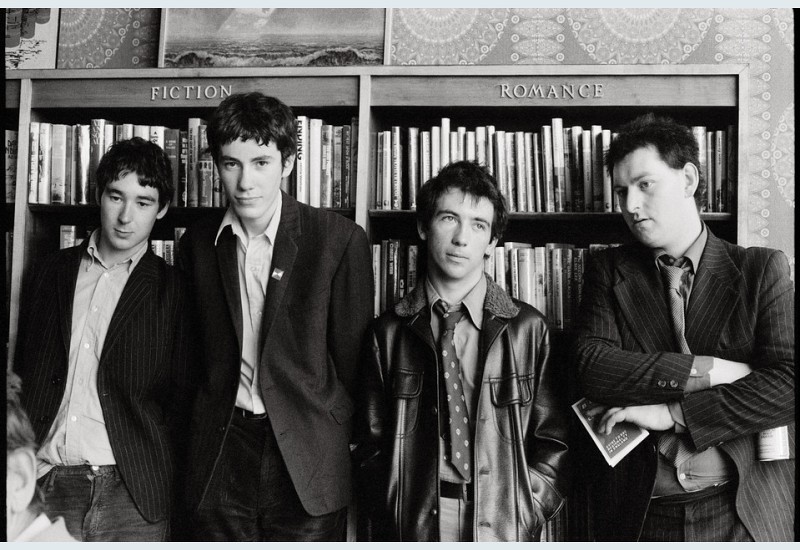

From a retro photo ex during Punk London last year. Photo from early 1980s by Fred Burstein.

At the gig, the Sex Pistols’ manager, Malcolm McLaren, introduced a young musician named Steve Diggle to singer Howard Devoto and guitarist Pete Shelley, who quickly formed Buzzcocks to open for the Pistols when they returned to play again six weeks later. “The next day we had the first rehearsal,” says Diggle over the phone from England, “and we all plugged into the same amp at Howard’s house and did ‘Boredom’ and ‘Orgasm Addict’ and I had this song called ‘Fast Cars’ that we did too.”

All three tunes would become blueprints in the sonic architecture of punk, just as the band’s wedding of doomed romanticism with great pop hooks leaping out of Pete Shelley’s warbling vocals, would exert a gravitational pull over the first punk bands to break out of the underground and burst onto the mainstream charts: Nirvana and Green Day in the early 90s. Both groups have name-checked Buzzcocks as influences.

In fact, when the late Kurt Cobain came to see them play in Boston, he wanted to know how Diggle had gotten that raspy vocal sound on “Harmony in My Head.” “He sat on the tour bus and asked me how many cigarettes I had to smoke to get that sound. He also asked how I’d survived all these years in the music business…” His voice trails off ominously. “Little did I suspect at the time.”

Part of Buzzcocks’ legacy stems from the fact they were the first punk band to put out their own record – the infamous “Spiral Scratch” EP – on their own label. At the time it was more a matter of necessity than a declaration of independence though. “If we went to a record company then they’d laugh us out of the building,” says Diggle with a wry chuckle. “This was some of the most extreme music being made then. So we made 1,000 singles, just to see how we sounded, and as soon as we put it out we had six major labels chasing us.”

As part of the 40th anniversary celebrations of punk in the UK, Buzzcocks appeared at the British Library for a special talk, bolstering Diggle’s claim, “We were punks with library cards.” The singer and main songwriter Pete Shelley, who died of a heart attack in December 2018, when asked what his definition of punk was, said, “”For me it was about being an active participant in your culture rather than being a passive consumer. I’ll have that on my headstone.” Indeed, it would make a great epitaph for the man who penned many indelible classics of that age. For many of us who started forming bands during that era tracks like “Boredom,” “Fast Cars” and “What Do I Get,” were punk starter-kits.

In the last main interview with Pete Shelley, he and Steve Diggle discuss the early days of punk with verve, wit and total frankness.

As the founding fathers of the genre moved from outliers to insiders, as the sound mutated into hardcore and splintered into a dozen different offshoots like cow-punk and punk-funk, as the Sex Pistols and Dead Boys split, the Clash racked up Top 40 hits, the Ramones teamed up with famous producer and homicidal nutcase Phil Spector, and the Damned went Goth, punk foundered.

By the time it reached a mainstream audience in the 1990s the shock value had long lost any cultural voltage and the stage was set for a watered down version, scornfully referred to as “mall punk,” to scale the charts and go into heavy rotation on MTV.

The Buzzcocks in 1977 at the exhibition Punk London held in 2016, with Steve Diggle (far left) and Pete Shelley (second right). Photo by Jill Furmanovsky.

Oh yeah? As a musical force it’s been dead for years.

IS PUNK DEAD?

On the 40th anniversary – perhaps 50th if you include the Velvet Underground and the Stooges – are there still any vital signs of punk left in popular culture or just some reverberations of nostalgia?

Certainly the more faddish elements have been relegated to documentaries of that era: the dog collars, plastic sunglasses, safety pins, and the habit of spitting on bands. Much of the derivative music has not survived outside Youtube and some Facebook fan pages. The original venues like CBGB in New York and the Roxy in London are long gone. Tattoos, piercings, torn jeans and spiky hair are fashion clichés for millenials.

Even some of the anniversary tributes seemed misplaced, like the exhibition, Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk, which ran until February 28, 2017 at the GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles. Hold on a second. The Ramones only received a belated GRAMMY Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011, long after Joey, Johnny and Dee Dee had passed away, because they never had any hits or commercial success. As influential as their first album continues to be – it was reissued in 2016 with a special mono mix that the group originally wanted because they loved the Beatles – it was not certified gold in the US, meaning sales of 500,000 copies, until almost 38 years after its release.

The mainstreaming and late-blossoming recognition afforded punk pioneers by the musical establishment has been the subject of much scorn. Among the dissenters is Joseph Corré. The son of the late Malcolm McLaren and fashion designer Vivienne Westwood burned some US$7 million worth of punk gear and memorabilia on November 26, the 40th anniversary of the Pistols’ first single, “Anarchy in the UK,” being unleashed.

Best known for cofounding the lingerie line Agent Provocateur, Corré told the Wall Street Journal, “Punk rock doesn’t exist. It’s extinct, and all you have left is some sort of tourist attraction. If you’re going to celebrate it, let’s celebrate it properly and burn it all.”

A Sid Vicious doll also got torched during Corré’s bonfire of punk memorabilia.

Not unlike his father who, during his stint as the New York Dolls’ manager, had them dress in red vinyl and play in front of communist flags on the ill-fated “Better Red Than Dead” tour, Corré is fond of the grand gesture.

But would such an act of arson really firebomb punk’s past and legacy?

For those of us who lived through that era, and played in bands, booked our own shows, created music labels and fanzines, fashioned our own clothes from thrift store castoffs, DJ-ed on campus radio stations, and fended off the constant threats from and attacks by rednecks at a time when a man with dyed hair, or a woman wearing a nose-ring, were radical fashion statements to be sneered and spat at, it was precisely that DIY ethos which was the movement’s mainspring.

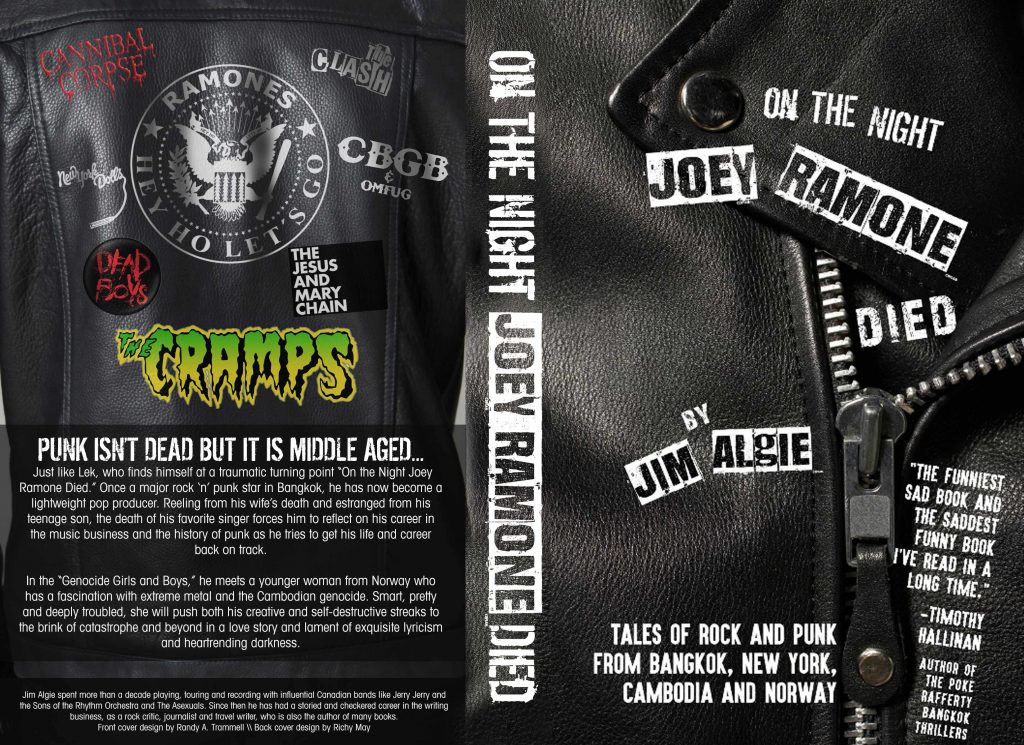

Which is also why, when I was considering putting out my new series of interconnected novellas, On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of Rock and Punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway (Magic Bullet Press, ebook released in 2017) that deal in part with punk history and some of my own experiences playing in bands, I didn’t go back to the bigger publishers I’d worked with before. No, I banded together with a few friends to make the book an all-indie affair.

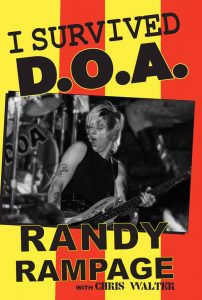

Chris Walter helped the notoriously rowdy bassist of D.O.A write his recent memoir.

Chris Walter is another independent author from Canada who has taken a similar route. The founder of G.F.Y Press has written many novels of what he calls “lowbrow lit for the wild at heart,” as well as biographies of Canadian punk stalwarts SNFU and Personality Crisis. Via email, Chris says, “For me, and I’m sure it’s different for other people, punk is about making my own rules and following my own path. Punk taught me to rely on myself and trust my own instincts. Punk taught us all to think for ourselves. We don’t need laws and rules. If the doors won’t open, kick ‘em down.”

The author, whose first big punk show was seeing the Ramones in 1980, makes some valid points. Through punk we also tried to take control of our own lives back from the powers-that-be, the major labels running the music business and the corporations colonizing the planet. You don’t have to be well versed in Noam Chomsky to see the same anger and frustration running through the Occupy Movement and the rebellion against the 1 percent who control the vast majority of the planet’s wealth.

So Joseph Corré can burn as much memorabilia as he wants. And the critics can rightfully say that punk is dead as a creative force in music, because it has become just another genre like reggae or rockabilly, fenced in and mapped out by strict parameters that are a long way away from Joe Strummer’s famous claim: “Punk’s first rule is that there are no rules.”

That does not change the fact that the indie, DIY spirit, whether in music, film, fashion, art, literature, organic co-ops, or small online shops, which is the movement’s most enduring contribution to unpopular culture, is still very much alive.

Founding members of the Buzzcocks in 2009, Steve Diggle, far left, and Pete Shelley, far right. Photo credit: Ian Rook

As the Buzzcocks prepared for their final bandstands of the anniversary tour in late 2016, singer and guitarist Steve Diggle, who takes heart in the younger audiences they’re attracting nowadays, has also gone back to his indie roots, using a crowd-funding campaign called PledgeMusic, which he calls the “most punk thing in years,” to finance a new solo album, Inner Space Times, exactly like fellow old-school punks the Vibrators are doing. (The new Damned album was also funded through Pledge Music, where you could get a guitar lesson from Captain Sensible via Skype, which is no longer available, but a host of other options and special vinyl editions are still up for grabs.)

After making poor Steve suffer through a long rambling digression about how much the Buzzcocks meant to me and my bandmates as teenagers forming our first groups, how “Boredom” and “What Do I Get?” were some of the first songs we learned how to play, to which he humbly says, “Cheers, mate,” I ask him the most puzzling question of all. How to sum up the last 40 years of his experiences on the front-lines of a movement that went from the grungiest basement clubs to the glitziest corporate boardrooms and halfway back again?

“When we started we were living in the moment, so you didn‘t think beyond the day, never mind four years or 40 weeks. Punk was such a powerful force that split the atom and caused a huge explosion that changed music and it changed consciousness. You could see people coming alive, getting excited and starting to question things. It’s only after 40 years that we’re really seeing the total impact. Nobody thought it would last this long, but it has been an amazing journey.”

The Ramones live in Toronto in 1976. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

This story is included in the revised and expanded 2018 edition of “On the Night Joey Ramone Died,” which includes a 130-page bonus nonfiction section of “Rock Writings and Musical Memoirs” and a front cover blurb from the acclaimed author and hit songwriter, Timothy Hallinan: “The funniest sad book and the saddest funny book I’ve read in a long time.” The ebook goes for 3.99 and a new paperback edition is also available from Amazon for US$12.99.

They just end up on the Grim Reaper’s guest list.

Su-fucking-perb!

Well done, Jim. One of the best articles I have read in years.

Thanks, Thom. Much appreciated.

Many thanks for the positive feedback, Thom.

Not to be a saddo pedant but the author seems to have been around long enough to surely know that it’s just-plain “Buzzcocks” and not “the Buzzcocks”.

The “Fiction Romance” photo is from 1977, not 1978. (Garth is in it, thus carbon-dating it to 1977.)

(Also, typo alert: “[Hilly] thought they had show [sic] up to rob the place.”)

Nice article otherwise.

Thanks for the comments and fact-checks. Consider the mistakes corrected. Nice to hear from a true Buzzcocks-ophile.