Many musicians have adopted guerilla poses and advocated armed insurrection – like The Clash and the MC5 – but none of them ever put down their guitars to take up a machine-gun like the Myanmar musician and rocking revolutionary, Mun Awng. In this profile that began in 1998, on the tenth anniversary of the 8/8/88 uprising, revised in 2007 after the “Saffron Revolution” of protesting monks, and has now updated again in 2017, he talks about his career in music, his stint in a rag-tag group of rebel soldiers, and as a pirate radio broadcaster in Norway. With the gradual opening up of Myanmar in recent years, many of his hopes have now been realized yet he remains in limbo.

Story by Jim Algie

Photos courtesy of the Irawaddy Magazine

The Burmese singer, wearing a red headband emblazoned with a golden peacock that symbolizes the outlawed National League of Democracy party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, took the stage in Bangkok to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the 1988 uprising in Burma. Armed now with only an electric guitar and an electrifying voice, instead of the gun he had carried as a rebel soldier, Mun Awng introduced the first tune.

“This song translates in English as ‘Tempest of Blood.’ It’s about the massacre that began on August, 8, 1988, and the lyrics come from a poem written by a student leader named Min Ko Maing. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison back in 1989 and is still in solitary confinement. The poem talks about how the blood shed in the streets will never disappear. When the sun shines, it vaporizes and forms a big red cloud that rains down on the streets, and into the rivers and the seas,” he said, before beginning his solo show.

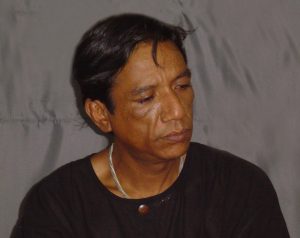

Myanmar musician Mun Awng busking on the streets of Oslo, Norway. Date unknown.

The Burmese students on hand, wearing the same headbands as the singer, shouted out every word of the song while clapping their hands and stomping their feet, as the minor-key verses – echoes of Neil Young – exploded into a rabble-rousing chorus. And you did not need to speak Burmese to understand the emotional overtones of this rallying cry. It was the sound of a people, choked by censorship and beaten down by the military, spitting out their rage over the junta’s killing of some 3,000 protestors on the streets of Rangoon.

Mun Awng, the stage name of Dennis Daws, was one of those protestors. When he saw television footage of the 2007 protests in Burma and the detainment of monks, from his home in Norway, it was almost a déjà vu of 1988, “except there was more shooting then and people look even poorer and thinner now than before. They didn’t use riot police this time I think, but that’s the only difference,” he says over the phone.

Did the monks also participate in the 1988 protests?

“They joined in, but this time they led the people. A lot of people really hoped that the army might compromise and not do any shooting but they expected a lot. I was very skeptical and I never underestimate this military,” he adds.

In 1988, Mun Awng was at the pinnacle of pop stardom in Burma. But his nasty experiences during the bloodbath, like watching a friend get shot in the cheek, the bullet coming out through his throat, and seeing the severed heads of protesters lining a street corner in Rangoon, forced him to change his tune. Shunning the spotlight, he joined a rag-tag army of young dissidents named the All Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF). From a base camp high in the jaggedly mountainous jungle along the Thai-Burmese border, he and his fellow soldiers-of-conscience waged guerrilla warfare against the heavily armed junta. “It was a losing battle,” says the 47-year-old. “We didn’t even have enough to eat.

“When I became a soldier I realized that mentally I could do it but physically it was difficult to live in the jungle, sleeping anywhere, always having to sleep with your gun on your right side, your bullets and equipment on the left side, so you’re always ready for an attack even when you go to the toilet. I didn’t enjoy being a soldier, but I wanted to show my solidarity with the other students,” says Mun Awng, who was born into a Christian family in the northernmost state of Kachin, where his father taught English and Mathematics.

Then, he and his fellow troops thought the junta might be overthrown in a couple of years. Now, he says sadly, some renegades from the ABSDF are still fighting up in the no man’s land of the Thai-Burmese border.

This portrait of Myanmar musician Mun Awng was shot by Moe Kyaw in 2004 in Mae Sot, Thailand

Myanmar Musician and His Battle for Peace

Abandoning the front lines for a recording studio in Bangkok, he laid down the tracks for his fifth, and most political album yet, called Battle for Peace (released in 1992). For the first time, he was not muzzled by the censorship laws that govern every aspect of Burmese society: music, TV, paintings, magazines, and radio.

Even though his first four albums were heavily censored, Mun Awng built up a sizeable following. His most vocal supporters were university students, says the editor of TheIrrawaddy, Southeast Asia’s most hard-hitting magazine about life behind Burma’s “Bamboo Curtain”. Aung Zaw recalls listening to his early albums in tea shops, along with other students, who were similarly impressed by Mun Awng’s melodic depictions of “life, struggle, courage, romance and some philosophy,” he writes in an email.

Some of the banned songs of this Myanmar musician like “Scarecrow” became touchstones for pro-democracy revolutionaries, who sang them at clandestine gatherings on college campuses, often in ladies’ dormitories. “We played all night,” writes Aung Zaw, “and in some cases we would tell the girls in advance so they could prepare food and snacks, cheroots and song requests that the security guards would come and deliver. Sometimes they [the guards] would tell us to go away, or [they would] stay and listen all night.”

At these jam sessions “Scarecrow” was a much-requested song that is still in demand at rallies today. It was written from the perspective of a rank-and-file soldier in the junta. As Aung Zaw translates the lyrics, ““Dead or alive, sacrificing my life for my country/Gold and silver stars on my shoulder/Oh my friend, what honor and rewards I would get/My heart is crying while my mouth was muzzled from telling the truth/A pierce through my eyes which have seen the truth/Oh my friend, I am a scarecrow in human form/Though I am alive, I am no longer living.”

Taken on April 13, 1999 at a concert to celebrate the Burmese New Year, or Thingyan, in Mae Sot, Thailand

In the genre of anti-war songs that usually take aim at the military industrial complex (Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War”), or side with the victims and the underdogs (Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier” or “Tommy Gun” by The Clash), Mun Awng’s tune is one of the few that dares to bridge the battle lines by showing the oppressor how he’s being oppressed.

The junta silenced this campus tradition by closing many of the universities. And some of Mun Awng’s musical contemporaries from that era like his close friend Ye Lwin (the bassist and songwriter for Mizzima Wave) were jailed for their political allegiances during the 2007 crackdown.

Throughout the 90s Mun Awng was one of the few Burmese voices to be heard inside and outside Burma, both as a singer and a pirate radio broadcaster. His 1992 album Battle for Peace was accompanied by a tour of Burmese refugee camps in Thailand. Thousands of his cassettes were given away for free. He also worked in a small studio along the Thai-Burmese frontier recording news programs, radio dramas and songs by himself and other singers, which were mailed to Oslo. In Norway, on a powerful radio station, the programs were beamed back into Burma seven days a week for 30, and then 90, minutes per day. Because the junta rained bombs on any of the studios or pirate radio stations along the border, he was eventually reassigned to Norway, where he became the manager of the Democratic Voice of Burma station.

The shock of landing there, when the country was locked in the crypt of winter, is still fresh in his mind. “It was 35 degrees Celsius when I left Bangkok and minus 14 in Norway. I’d never seen so much ice and snow in my life,” laughs the musician, who, inspired by local pop singers and The Beatles, began playing guitar and singing when he was still a boy.

Uncomfortable with being the boss, and feeling that he was not on the same wave-length as some of his cronies, he resigned after three years on the station, believing that he could do more for his people as a protest singer than as a radio broadcaster or a soldier. “The best thing about music is… there’s no bloodshed,”

Myanmar musician and pro-democracy activist Mun Awng.

he notes.

In Oslo, with an accomplished band of local musicians laying down the bedrock of drums and bass, embellished by strings, keyboards, and saxophones, he recorded Path to Freedom in 1998. Many of the songs on it, he says, were passed down in true blues fashion from one musician to another – campfire music for outposts of Burmese dissidents and refugees.

Then he embarked on another series of gigs at refugee camps, including a nursery, “the best gig I ever had,” he says with a smile in his voice. Once again he gave away thousands of free cassettes, some of which were smuggled into Burma, a risky enterprise considering his name is blacklisted from all forms of media in the country, though some of his albums can still be purchased under the table in shops. This tour of duty culminated with the raucous show in Bangkok to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the pro-democracy revolt in August 1988 that resulted in a death toll of some 3,000 souls.

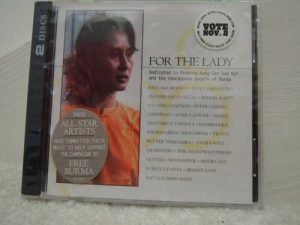

Mun Awng was the only Myanmar musician included on this tribute album to Aung San Suu Kyi, which also featured U2, Coldplay and REM.

TEMPEST OF BLOOD

Six years later, the song he played first that night, “Tempest of Blood,” with lyrics by the still-incarcerated student leader, became the climactic track on a two-disc benefit album called For the Lady: Dedicated to Freeing Aung San Suu Kyi and the Courageous People of Burma the song he played first that night, “Tempest of Blood,” with lyrics by the still-incarcerated student leader, became the climactic track, alongside tunes by U2, Coldplay, REM, Pearl Jam and Ben Harper. Mun Awng is the only Myanmar musician on the album. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says, “being on this album with all these huge stars. It was exciting. I really didn’t think it would happen. We’d already distributed the song for free, so why not put it on the album?” he says, laughing off his sheepishness.

Either on- or off-stage, and even in exile, Mun Awng retains that happy-go-lucky spirit one sees so often in Burmese people and which seems all the more remarkable for the hardships they’ve had to endure since martial law became the rule of thumb in 1962. Even his sister, who is a veterinarian and still lives in Kachin state, makes the usual civil servant’s wage of around US$15 dollars per month.

At the time, it seemed like the the star turn of this Myanmar musician on the benefit album could turn out to be his swan song and death knell. Over the next few years, he only performed live at a couple of Burmese fund-raisers in Japan and London. He did not write or record any new material. There was no audience for his brand of agit-pop in Norway. And in the village outside Oslo where he lived with his Burmese wife and their daughter, the singer and guitar-slinger, who also holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Mathematics, was working in a wood-coating factory. “Music is very far away from my life now. I have to pay my daily bills,” he says, laughing again, but this time it sounds brittle. This time there’s a note of resignation in it.

Still, Myanmar’s most famous musical exile remained hopeful that the military regime could not tyrannize Burma forever.

“I do have hope. As far as I know, they [the pro-democracy protestors] are not giving up. I think almost everyone in Burma wants a change. Only a handful of people who are enjoying the riches want the regime to continue. Everyone else is fed up. People love Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and that’s what makes the military afraid of her. She is one hope for Burma. We have many activists working and ready to sacrifice everything, but they are always working behind the scenes, not on the front lines.”

In spite of the junta’s intransigence and the fact they banned Aung San Suu Kyi from participating in the first elections to be held in years, Mun Awng was buoyed up by his faith in the Buddhist law of impermanence.

“In the Burmese way, in Buddhism, anaisa means nothing exists forever. There will be a change. I just hope we are alive when that day comes.”

And when Myanmar did begin to open up again in 2011 and then Aung San Suu Kyi won a landslide victory in the landmark 2015 elections, the stage was set for the return of this legendary Myanmar musician and activist, who had returned to live in northern Thailand.

2017 UPDATE

After almost 20 years since I first saw him play at the FCCT and interviewed him on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of 1988 uprising, and followed up with more interviews via phone and another story after the 2007 Saffron revolution, I’m overjoyed to say that he released a comeback album, Raindrops of Peace, in late 2016, and has finally been allowed back into the country to play shows too, including a solo performance in Rangoon in February 2017, capping one of the most unlikely and incredible comebacks in music history.

Poster for the 2017 solo show in Rangoon by Myanmar musician and rocking revolutionary Mun Awng

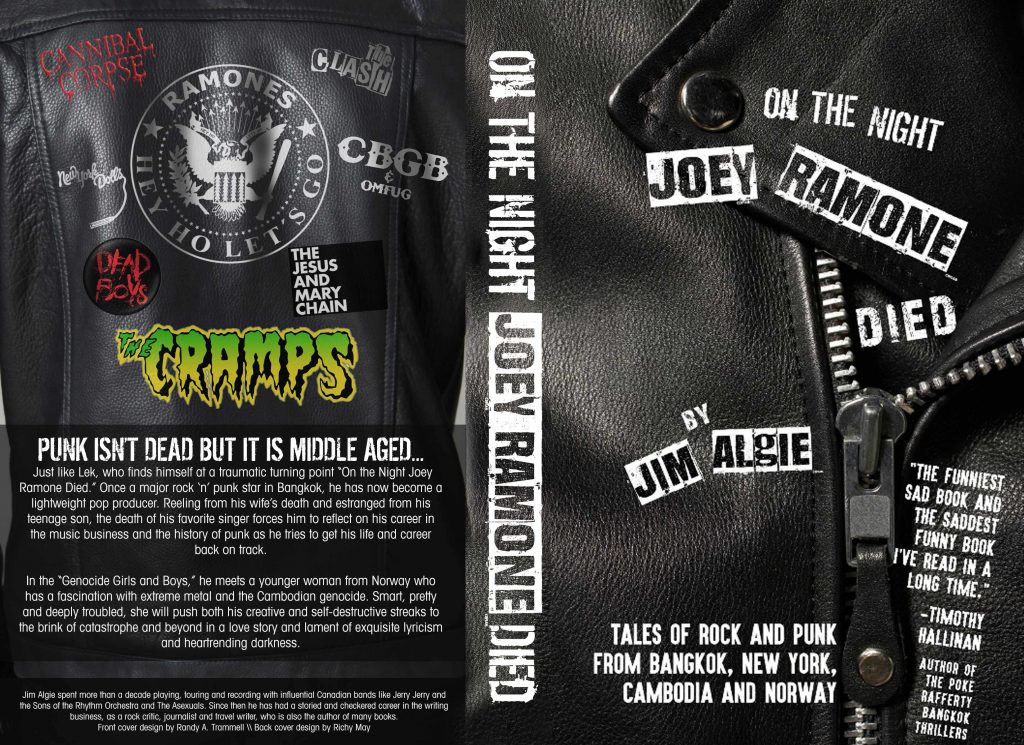

For more rocking tales by Jim Algie give his book, On the Night Joey Ramone Died, a spin. The ebook is available from Amazon for the pittance of US2.99 while the expanded paperback edition, which comes with a 130-page nonfiction bonus section of “Rock Writings and Musical Memoirs,” is now available from Amazon for US$12.99.

The new paperback edition of On the Night Joey Ramone Died released in February 2018 through Amazon.

Recent Comments