The passing of the cult-famous punk singer of SNFU last year inspired a torrent of online tributes from fans, critics and musicians like Billie Joe Armstrong of Green Day, but few of them came from those who first knew him as a teenaged skateboarder from Edmonton.

Words by Jim Algie

Anecdotes from Marc and Brent Belke, Evan C Jones, Guido, et al

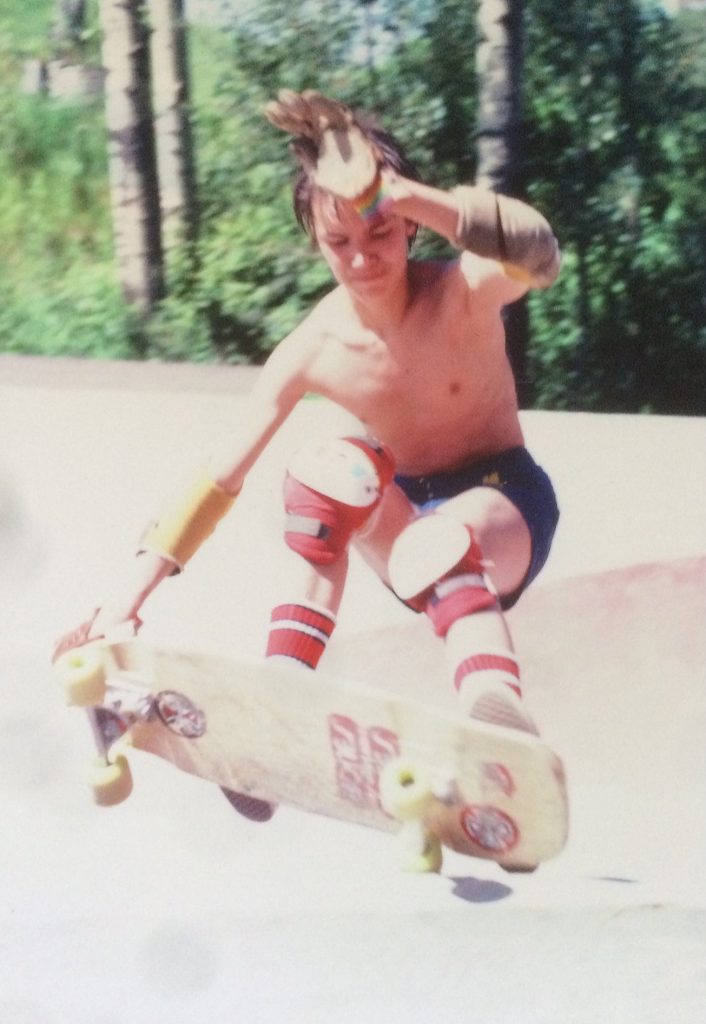

Kenny Chinn was not the best nor the bravest skateboarder in Edmonton of the late 1970s – those honours went to his younger brother Danny – but he was one of the most graceful. Whether he was spinning 360s with his arms crossed over his chest, carving across the walls of empty swimming pools in a crouch, or grinding the axles that skaters call “trucks” across the lips of bowls and ramps, one arm over his head like a rodeo rider atop a bucking bronco, Ken took an artistic rather than athletic approach to the sport.

All those manoeuvres served as the jumping off point for his stage antics as the lead singer of SNFU, which either meant Society’s No Fucking Use or as bassist Jimmy Schmitz claimed, “Silly Name For Us.” The Edmonton (and later Vancouver) group developed an international following over the zigzagging course of an almost 40-year career, breakups and hiatuses aside. Under the pseudonym Mr. Chi Pig, Ken’s most repeated stage move was leaping off the top of the bass drum like a skater without a board catching air off the top of a ramp.

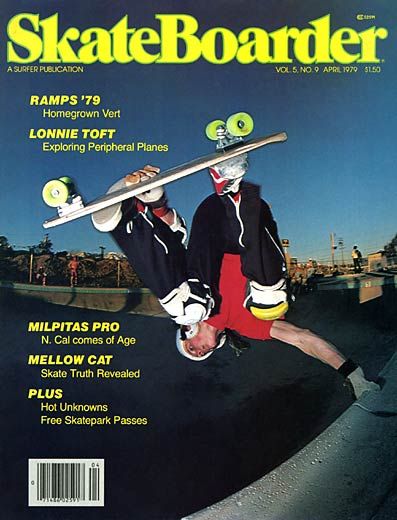

Vintage issue of Skateboarder magazine from 1979

Ken skating the bowls at Lake Eden, Alberta in 1979

We first met at a local half-pipe in front of a sports store when we were 16 and struck up a friendship based on skateboarding and going to Victoria Composite High School, where we looked like two of the scrawniest weirdos around. He had Chinese looks and rubbery facial features. I had glasses and braces. Both of us stuck out like broken arms in casts that none of the other students wanted to sign.

The more popular kids had no need for punk rock. They had friends, football games, chess clubs, cheer squads and science projects to worry about. They had good grades and reputations to maintain. We shared none of their interests or concerns.

It was skateboarding that inspired our interest in punk and new wave, because the heroes we followed every month in “Skateboarder” magazine, like Tony Alva, Steve Olson and Duane Peters, had all gotten spiky haircuts and talked about how much they liked the Ramones, Devo and the Sex Pistols. On a visceral level, the speed and aggression of the music excited the same adrenaline rushes and endorphin highs that the sport induced. It was music that sounded like it was careening out of control and about to crash.

We were such skate-geeks that when Devo played their first Edmonton show at the University of Alberta’s Sub Theatre in 1979, Ken, me and my brother, Richard, rode to the show on our boards, clad in matching black T-shirts that we’d gotten silk screened with the band’s name across the front and wore our helmets while pogoing throughout the gig. (Yes, we were totally that uncool. None of us could even stomach the taste of beer, so we drank apple cider.)

We were such skate-geeks that when Devo played their first Edmonton show at the University of Alberta’s Sub Theatre in 1979, Ken, me and my brother, Richard, rode to the show on our boards, clad in matching black T-shirts that we’d gotten silk screened with the band’s name across the front and wore our helmets while pogoing throughout the gig. (Yes, we were totally that uncool. None of us could even stomach the taste of beer, so we drank apple cider.)

After school, and during the summer holidays, the three of us worked elbow to elbow as dishwashers in the hell’s kitchen of a five-star restaurant called Blackbeards, where we earned – and encouraged – the enmity of most staff members by blasting punk tunes (DOA, The Clash, Pointed Sticks, Dead Kennedys) on a ghetto-blaster in the kitchen.

In our last year of high school at Vic Comp, Ken and I hosted the only weekly radio show of punk and new wave songs on the school’s Redman Radio station. The backlash against the program was so severe that we had to barricade ourselves inside the radio room and keep the music turned up loud enough to drown out the jocks jeering us through the locked door. “Punk sucks, you faggots.”

We’d sit there, look at each other, laugh and try to play another song that would upset them even more. If we couldn’t get a positive response out of the other students, then negative feedback was just as stimulating, and if we couldn’t be famous as athletes, “brains,” pretty boys or the valedictorian, it was far better to be infamous than to be ignored.

Members of the Redman Radio Club at Vic Comp. Ken Chinn is in the front row, far right. Jim Algie and Michael Charrois are the bespectacled duo in the back. Mike is holding a magazine.

I don’t know how much we learned in high school – Ken only enjoyed the art classes in which he excelled – but we learned a lot about music from doing that radio show: how songs could exorcise all sorts of demons and pent-up frustrations, serve as “asshole repellent” to antagonize the kids we hated and did triple duty as rallying cries to attract other like-minded outcasts who felt the same way we did.

After the mainstreaming of punk music and fashions in the 1990s, when dyed hair, torn jeans and pierced everything, became business as usual instead of freak-show abnormal, it would be hard for millennials to imagine how threatening punk rock, and seeing a guy with green hair or a girl with a nose-ring, were back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Almost every day at school, we got threatened, pushed into lockers, harangued and ridiculed, the same as many other punks did in this redneck oil town. Somebody stuck a lit match down the vent of my locker and burned all my books and notes. A jock, built like a bulldozer, threatened to kick our heads in if we dared to attend the senior prom, which was the ultimate social event of those three years. Even if we had wanted to go we would not have been able to find dates anyway; there was only one punk chick in the entire school, and five other people who were into it out of a student body of a thousand. I know the exact number because I am still friends with all of them on Facebook.

In retrospect, the abuse had many positive side effects. It thickened our skins, gave us plenty of material to write about and provided a few insights into what it’s like to cling to the fringes of society, which Ken utilized in many of his future lyrics about everyone from abused kids to old women with Alzheimer’s disease. Like muscles, people need resistance to grow. High school was our resistance training.

In our last year there, when a female student in Grade 10 was gang-raped by a few of her classmates in a walk-up apartment down the street from the school, we formed our first band and began rehearsing in my mom’s basement. Ken was supposed to be the singer, I sort of played guitar and Richard could almost play drums. Our nameless outfit never played any shows, but we recorded a few originals down there on a Radio Shack cassette deck, like “Apple Jacks,” Ken’s tribute to his favourite breakfast cereal and, as aficionados of horror and cult films, we based another song, “Attack of the Killer Tomatoes,” on a midnight movie we caught at the Princess Theatre on Whyte Ave. Long before he wrote the lyrics to SNFU standards like “Cannibal Café,” Ken’s writings and artworks were firmly fixated on the macabre and grotesque; that was another obsession we shared.

In our last year there, when a female student in Grade 10 was gang-raped by a few of her classmates in a walk-up apartment down the street from the school, we formed our first band and began rehearsing in my mom’s basement. Ken was supposed to be the singer, I sort of played guitar and Richard could almost play drums. Our nameless outfit never played any shows, but we recorded a few originals down there on a Radio Shack cassette deck, like “Apple Jacks,” Ken’s tribute to his favourite breakfast cereal and, as aficionados of horror and cult films, we based another song, “Attack of the Killer Tomatoes,” on a midnight movie we caught at the Princess Theatre on Whyte Ave. Long before he wrote the lyrics to SNFU standards like “Cannibal Café,” Ken’s writings and artworks were firmly fixated on the macabre and grotesque; that was another obsession we shared.

For the most part, he was pretty easy to work with as a collaborator on the radio show and a songwriting partner, except his constant stream of sarcastic remarks, slurs and insults could pollute any atmosphere. There I was trying to play a serious Ramones-style guitar part – and he writes the lyrics about breakfast cereal? It was mockery and Ken loved mocking people. He nicknamed one overweight local musician, “Gus Pufferfish,” he referred to another guy with a receding hairline as having “miles of forehead,” and those are only a few of the more printable insults.

If he wasn’t so consistently hilarious, he would have been the most hostile little prick around. It took a few years to figure out where his anger came from. He never talked too much about his past except when he was drinking. Then a few secrets would seep out about his broken and battered home, his dad’s prison sentence, his 11 or 12 different brothers and sisters or step-siblings, the family’s poverty, all the pride-flattening insults he’d endured about looking Chinese. (Racism was much more overt in the decades before political correctness whitewashed but never fully erased it: “Chinks eat rats” was still a common slur and stereotype in the 1970s.)

At an age when the riptides of testosterone coursing through any young male’s bloodstream can take some violent turns that climax in fights, dangerous stunts, sexual harassment, shootings, drunk driving and wanton acts of vandalism, Ken was dealing with what was a much more taboo subject then. Most of his close male friends realized very early on that he was not straight. That was obvious. One of his favourite gags was to poke us in the balls and then laugh maniacally, screwing up his rubbery features to a comedic extreme and turning his smile into slapstick.

While the other guys were bragging about chicks they’d banged or felt up, or making jokes about how vodka is a “bottle of instant panty remover,” Ken’s takes on the subject of sex were always revolting. “Sex is like taking a shit,” he said over beers at the Rose Bowl, our local pizza place and watering hole, “it feels good at first then it starts to stink.” Nobody laughed harder at his own jokes than Ken Chinn.

He was already a touchy enough guy that nobody was going to ask him about his sexual preferences. One night, when we were 19 or 20 and trying to walk into an Edmonton tavern, the bouncer refused us entry because he didn’t like the looks of us. He waved goodbye and tacked on a sarcastic, “Bye.” With only a split-second pause, Ken replied, “No, we’re straight.” (Bye and bi; bi, gay and straight. Get it? Ken loved puns and wordplays.)

Toss in all the high-school abuse we suffered and few singers had the angst and the bona fides he did to become one of the angriest, and often one of the funniest, voices of his hardcore punk generation.

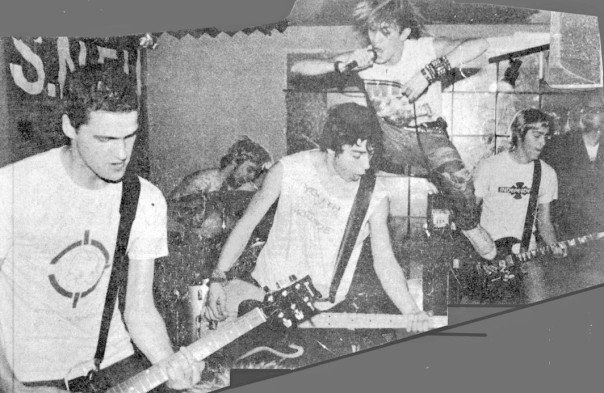

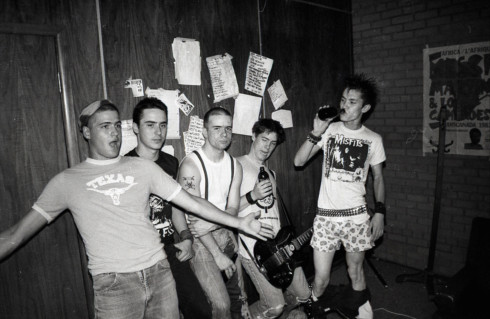

SNFU onstage around the time of their first album release in 1984.

He channelled some of that frustration into his artworks, filled with phallic imagery, and into the lyrics and performance of SNFU’s breakout song, “Womanizer” or “Victims of the Womanizer,” included on the 1984 compilation album Something to Believe In. The first few times I heard the song it was the last line of the chorus that hooked my attention: “He’s all right, he’s okay, prove to the world that he isn’t gay.” At the end of the song he repeats the last part of that line over and over again with increasing ferocity. During live performances he would often flick his wrist in the air in an effeminate caricature of homosexuality while he sang that line. It wasn’t a song about gay pride, though. This was gay shame with a feminist twist. The narrator of the song empathizes with the woman who’s been sexually abused by this creep when she’s passed out in a drunken stupor. In the next verse she commits suicide.

The lyric works on a number of levels; it’s hostile, empathetic and sorrowful; but the horsepower of the song comes from the Belke brothers, Marc and Brent, on guitar, as well as the furious tempo laid down by Evan C Jones on drums and Jimmy on bass.

It didn’t require much detective work to figure out that the “womanizer” in question was a guy we both knew, who shall not be named. From insults tossed around in the bar and in between rides on a skate ramp, Ken had kicked them up a notch to attacking people through his lyrics. He was already enough of a nasty prick as it was. Now that he had a mic and a stage he was getting even nastier. Many of us could relate to that. Anger was all the rage in that musical generation.

In songs like that he staked out some very different lyrical terrain, largely uninhabited by other hardcore singers of that era, except perhaps Minor Threat and the Subhumans in “Slave to My Dick.”

This past October, in Victoria, BC, I tipped a few beers with guitarist Marc Belke, the second-longest-surviving member of the group, who wrote much of the band’s music, for the first time in 30 years. Marc says, “I think Chi thrived on being this unique being. I think he got strength from it. He loved being a punk rocker and we found something in it that we identified with probably for different reasons. For me I think it was because too many people were telling me what to do all the time.” He shrugs and pauses. “Punk became part of our personalities.”

Ken and I first met Marc and Brent Belke, known later as Muc and Bunt, respectively, the twin brothers who became the twin guitar engines in SNFU’s super-charged sound, when we were skateboarding. They were a couple of years younger than us. They had also gotten into punk through Skateboarder magazine. In the 2012 biography by Chris Walter, SNFU: What No One Else Wanted to Say, Marc recounted how I taught him how to play barre chords in my mom’s basement. The jamming area I set up was next to the lawn mower, the freezer and some hedge clippers hanging from a nail on the wall; proof positive how middle-class Canadian punk was.

Ken and I first met Marc and Brent Belke, known later as Muc and Bunt, respectively, the twin brothers who became the twin guitar engines in SNFU’s super-charged sound, when we were skateboarding. They were a couple of years younger than us. They had also gotten into punk through Skateboarder magazine. In the 2012 biography by Chris Walter, SNFU: What No One Else Wanted to Say, Marc recounted how I taught him how to play barre chords in my mom’s basement. The jamming area I set up was next to the lawn mower, the freezer and some hedge clippers hanging from a nail on the wall; proof positive how middle-class Canadian punk was.

The four of us wrote a couple of songs down there, like “Let’s Go to Sportsworld,” a satirical ode to a local roller-skating rink called, stupidly enough,Sportsworld, which is only worth mentioning in passing because it represented the zenith of teenage entertainment in a city the punks dubbed “Dedmonton.”

Boredom, not political revolution or class warfare or any of the higher ideals espoused by members of that punk generation, served as the main catalyst for many of us middle-class kids to join the punk/new wave scene. Tellingly, “Boredom” by the Buzzcocks was the first punk cover that the four of us learned how to play together.

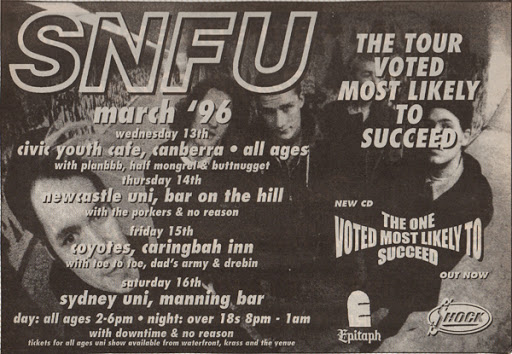

SNFU tour of Australia in 1996

2: On the Rise

With very few exceptions, such as 20,000 Days on Earth, the half-fictional movie about a day in the life of Nick Cave, the classic music documentary format is a three-act play. The first part chronicles the band’s rise to fame. In the case of SNFU, their heyday came in the 1990s. Signed to Epitaph Records in LA, the group recorded three albums for the indie stalwart that sold a combined total of more than 200,000 copies. For a Canadian punk band that was exceptional, but it was pocket change compared to their label mates like Offspring, Rancid and Bad Religion.

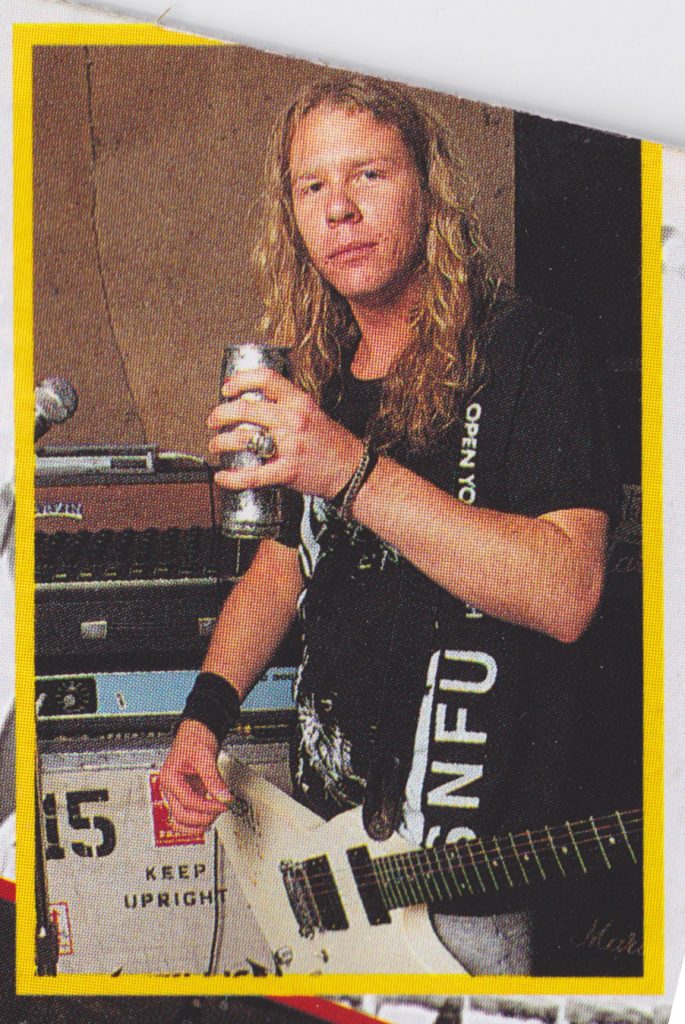

The group’s frenetic live shows won over loads of fans and a number of rock stars like James Hetfield of Metallica, who was photographed wearing an SNFU shirt on one of their albums, as well as a 16-year-old Billie Joe Armstrong from Green Day, who put up an Instagram post after Ken’s death in July 2020 that sums up the outpouring of grief around the world: “Oh man. This breaks my heart. Chi Pig was one of the greatest front people I’ve ever seen. I saw SNFU at Gilman when I was 16. I thought he was going to jump through the ceiling. Super smart. Great lyrics. Amazing album titles. So funny. He had an amazing mask collection. Lead singer for SNFU. What a bummer. Sending love to all the Edmonton and Vancouver punks. What a loss.”

Onstage SNFU was a perpetual motion machine. During any given verse, chorus or guitar solo, one or more of the band members was leaping in the air or up and down. Whoever was on drums, Evan C Jones or Jon Card, seemed to be levitating above his drum stool. When I saw them live, I often keyed in on Brent Belke’s energy. He never affected any kind of punk image. In contrast to the rest of the band, he looked like the normal kid turned school shooter, armed with a guitar instead of a gun.

Onstage SNFU was a perpetual motion machine. During any given verse, chorus or guitar solo, one or more of the band members was leaping in the air or up and down. Whoever was on drums, Evan C Jones or Jon Card, seemed to be levitating above his drum stool. When I saw them live, I often keyed in on Brent Belke’s energy. He never affected any kind of punk image. In contrast to the rest of the band, he looked like the normal kid turned school shooter, armed with a guitar instead of a gun.

In that circus of sound and stagecraft, Chi Pig was both the ringleader and the chief clown. He wore different masks and bonked audience members over the head with an inflatable baseball hat. At one show he threw a dead octopus into the mosh pit-melee. At another he brought a water pistol on stage to squirt fans in the face. Sometimes he’d dress in drag or put on a hand puppet and serenade it. At the gig Billie Joe mentioned in California (the sound and video get better after the first 15 minutes), Chi is wearing a red cowboy shirt and a plaid schoolgirl’s skirt.

As opposed to the macho posturing of Henry Rollins, whose stage moves looked like he was warming up to run a marathon after the gig, or the manic energy of Jello Biafra, who bristled with so much rage it was uncomfortable to watch him, Mr. Chi Pig, with all his funny dances and penchant for singing to the boys in the front row and putting his arms around them, brought some much-needed levity and androgyny into an overly macho genre that often took itself a little, or way, too seriously.

3. ROCKY ROAD TO THE BOTTOM

The second act of the typical music documentary covers the band or musician’s downfall. After their third and final album for Epitaph, SNFU floundered. Brent Belke and drummer Dave Rees left the group and Ken found himself at loose ends. Perhaps that was the catalyst for his descent into a maelstrom of meth addiction. Even by the abysmal standards of many musicians plummet from fame and grace, his downfall was wretched. He lost his apartment. He lost his teeth and, by all reports, he lost much of his mind.

For all the photos I saw and rumours I heard, it was hard to know the extent of the damage. I don’t think Ken ever had an email address or a cellphone. I never saw him on antisocial media. He didn’t seem to have a fixed address anymore or a regular job. It was nearly impossible to get in touch with him.

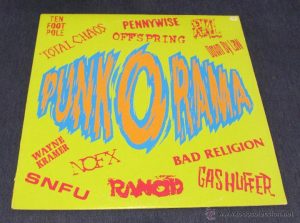

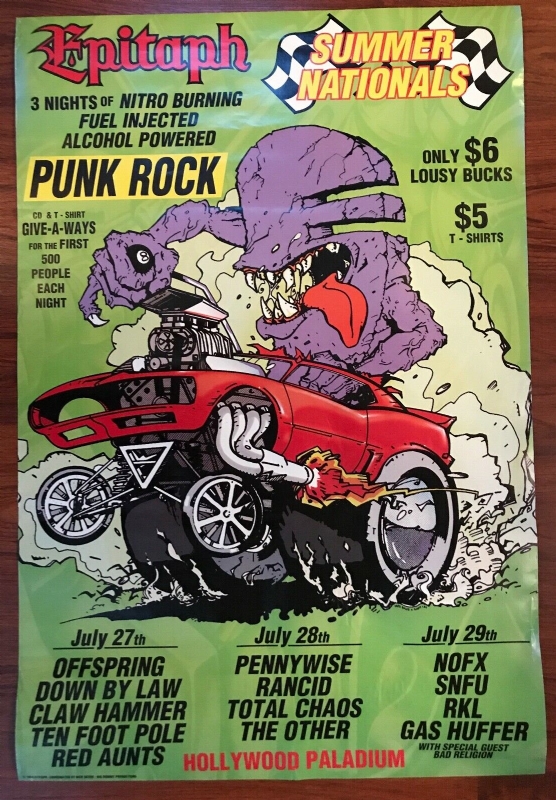

SNFU appeared on several of the compilation albums released by Epitaph in this series.

Whenever I was back in Vancouver I would spend hours walking around downtown looking for him. Mutual friends mentioned some of the bars he haunted, but he was a phantom who kept popping up in my thoughts but never appeared anywhere in the real world.

And the rumours about him, like how he’d come down with schizophrenia, kept getting weirder.

I didn’t have any advice to offer him. Wrestling with personal demons is not a team sport; it’s a marathon that you have to run alone. At the same time, I figured it might do him some good to see a friend he knew before the music days, or whatever it was, tripped his self-destruct switch.

But Ken had many reasons to be unhappy. After he “came out” in Vancouver in the 1990s once SNFU relocated there, I don’t know if he ever found love or even a lasting relationship. From what I’ve heard, I guess he didn’t find either. Now I’m not familiar with the entire discography of lyrics he wrote for SNFU, and his other bands the Wongs and Slaveco, but I don’t recall him ever writing any love songs. Maybe the adoration of his fans was the closest he ever came to finding the love that was denied him in his personal life.

Such a lonesome fate could drive anybody to drugs, drink and self-annihilation.

Of course, boiling down anything as complex as addiction to a few simple causes is too simplistic. The 2009 documentary about him, Open Your Mouth and Say… Mr. Chi Pig, explores the subject with more depth. In the film directed by Sean Patrick Shaul, which features interviews with many punk titans like Jello Biafra and Joe Keithley of DOA, Ken speaks at length about his fragile state of mental health, his drug use and the voices he heard in his head.

Lately, I reconnected with the band’s third-longest-surviving member, Brent Belke, on social media. We bounced a bunch of messages back and forth about how and why left he the band – mostly because the touring grind wore him down – and what happened to Chi. He says that the singer’s downward spiral, which included a nervous breakdown or two, was many years in the making. “These things happen slowly over time and then there’s this realisation that he’s hit rock bottom. It’s alarming for sure,” he writes in a message.

Whatever the myriad causes of Ken’s downfall, and no matter the state of madness he’d apparently sunk into – in a couple of photos I saw he looked like an Asian version of Charles Manson – I kept searching for him in the city’s underbelly.

Three-night music festival in LA starring Rancid, Offspring, Pennywise and SNFU

4. MEMORIES AND BLESSINGS

Over the last six months I’ve had so many different conversations and message exchanges about him that I asked people for their permission to post some of them. At the very least I hope they convey a little of what a deeply contradictory and insanely creative guy he was, as well as how many different people he touched both on and off stage.

In a follow up message to her reminiscences, Tamara Sapach Fulmes mentioned a Jewish expression in reference to a person’s passing, “May his memory be a blessing.” Yes, a blessing for many and a curse for a few others.

(All entries have been minimally edited.)

“I just truly always remember us always being stoned and drunk. On the road in the van we would draw cartoons on the walls and ceiling of Otto’s van (aka Daryl Stenson). I was laying back & was drawing a big eyeball on the ceiling, again quite stoned. I then wrote the “WORM EYE” as Where Am I & then Ken started drawing a very funny cartoon next to it of our roadie Daryl and it was of him with devil horns on his head, and of course right next to my big WORM EYE/Where Am I he wrote above his cartoon “OTTO NO”… That became ‘WORM EYE/OTTO NO SNFU TOUR 1984.” Those words are also the inner scratchings on Side A & Side B on the first album… And No Else Wanted to Play.” We were friends/bandmates/brothers him & I. Yup.”

Evan C Jones, original drummer in SNFU

“In 1988 I was in the Canadian Armed Forces stationed in Victoria, BC. SNFU was playing next door to my apartment and Ken was going to crash there while the rest of the band found other spots. Post gig we were chatting and enjoying some frosty beers. Two local young punks started hassling me saying loud enough for Ken to hear ‘that no real punk would be in the army.’ Ken turned around fast and tore right into their souls exclaiming, ‘Guido was a punk long before you two were and part of being punk is doing what you want to do no matter what others think – including other punks.’ Meekly they skittered away. True friendship on display.”

Anthony “Guido” Fulmes

Photo of Metallica singer with SNFU t-shirt

“Ken was a no bullshit kind of guy, which didn’t make this an easy life for him.”

Richard Algie, drummer in the posthumously named Ken Chinn Trio

A drawing by Lyle Shultz that Ken doodled on at the top.

“I consider’s Ken’s Art all one thing, THE Drawings, the performing, the lyrics, His Chi Pig personae. I think that’s what I learned most about Art from him. Having an original Artistic Identity.”

Lyle Schultz, musician and artist

“The first time I met Ken was outside the Spartans Men’s Hall, a rundown community hall across from the 100-year-old Transit Hotel. SNFU showed up and refused to pay the door charge but came in anyway. Ken came out the side door and was complaining he didn’t have a beer. I had two and offered him one. He kicked it out of my hand and walked away towards another group of teenagers sitting outside in a field. He didn’t look back.”

Lisa Swaren, Edmonton musician

“I was just talking politics in Safeway for 30 minutes with that Kenny Chinn. He’s such a polite and articulate young man.”

Pat Algie, my mom

“I first met Ken in our high school’s radio club, where we got to inflict our musical tastes on the student body at lunch time. He teamed up with Jim and those guys called their program, ‘The Bill and Bill Show.’ He played Bill Pomo and Jim played Bill Melater, which was a parody of a popular daytime CJCA radio show. I remember this because of the series of brilliant posters Ken produced and posted around the school. This poster idea was something he did to promote their show. It was an idea me and Jim borrowed to do our later radio show on the university station CJSR called The Pile on the Left Is Whiter.”

Michael Charrois, actor

“1998 and SNFU was in Ottawa for a gig. Guido and I have a nice place and I’m a good cook, so Casa de Fulmes is officially the band house. I get up early in the morning after the gig to make breakfast for everyone and on the floor of my living room is my 12-year-old daughter and Ken, colouring and crafting, giggling away in very conspiratorial tones. It was sweet and innocent and precious and it forever changed my opinion of him. I decided that the way he was onstage was a character he played. But when he was with Tori, I don’t want to sound melodramatic, but I saw a lonely little boy who didn’t get the hugs and cuddles I gave to my own child.”

Tamara Sapach Fulmes

Chi Pig drawing of band-mate Evan C. Jones holding a martini glass.

“I was leaving the Cambie pub in Vancouver after getting quite drunk one day and this guy came running up behind me and tapped me on the shoulder to give me back my phone, which I’d left on the table. He looked like a street person but I only found out later that he was this famous singer named Chi Pig. He didn’t look so great in those days but everybody told me he was still a nice guy.”

Mike Zyke, guitarist in the Doors’ cover band Unknown Soldiers

“In some of the last interviews and podcasts I watched with him he seemed very humble.”

Marc Belke, guitarist in SNFU, singer of the Wheat Chiefs

“The first time I saw SNFU in Montreal in the mid-1980s at Station 10, Chi dropped his mic on the stage and then started doing push ups while he sang into the mic. Never seen a singer do that before.”

Leroy, former frontman of Satan’s Landlord

SNFU in the early days. From left, Bunt, Jimmy, Evan, Muc, Ken in boxer shorts.

“When another Edmonton singer, Darren Taylor of the Carnival Cops, passed away before Ken in 2020 I was trying to think of a more positive anecdote about him to share on social media. One of the first things I remembered was the Cops’ debut gig at Spartans. Nobody knew whether this shy twitchy guy could pull if off as a front man, but he did and the show was great.

“Between groups I was standing outside drinking beer out of plastic cups with Chi, who was rocking a blond Mohawk and a studded black leather biker’s jacket with band names on the back and badges for different punk bands on the lapels. After spending every single day of high school together and washing dishes at night, skateboarding, jamming and going out to gigs on weekends, we didn’t hang out anymore except at gigs and parties.

“One big reason for that fracture was the underground music scene, which divided as many people as it united. Punk promised many things, like curtains for rock stars and levelling the music-biz hierarchy that it never delivered. As soon as the competitive aspects of the business entered the scene, recording deals, selling merch, making money, getting reviews in papers and magazines, winning fans and seducing chicks, the solidarity of the old days splintered into different factions and cliques. Ken and I ended up in different scenes. He was in hardcore. I was in roots rock. That was a big enough chasm, but even bands in the same genre took on this egotistical “We’re not playing before those guys” attitude. Ken, or rather his alter ego Mr. Chi Pig, also became an egomaniac. Now we greeted each other by our stage names, given sardonic twists of lemony humour. He’d say, “Hey Bleak,” and I’d go, “Hi, Mr. Pig.” Instead of friends we’d become musical rivals.

“One big reason for that fracture was the underground music scene, which divided as many people as it united. Punk promised many things, like curtains for rock stars and levelling the music-biz hierarchy that it never delivered. As soon as the competitive aspects of the business entered the scene, recording deals, selling merch, making money, getting reviews in papers and magazines, winning fans and seducing chicks, the solidarity of the old days splintered into different factions and cliques. Ken and I ended up in different scenes. He was in hardcore. I was in roots rock. That was a big enough chasm, but even bands in the same genre took on this egotistical “We’re not playing before those guys” attitude. Ken, or rather his alter ego Mr. Chi Pig, also became an egomaniac. Now we greeted each other by our stage names, given sardonic twists of lemony humour. He’d say, “Hey Bleak,” and I’d go, “Hi, Mr. Pig.” Instead of friends we’d become musical rivals.

“As Darren approached us, he looked more nervous and sheepish than ever. Within spitting distance of the razor-tongued Chi, he had had every right to start cringing in advance. SNFU were the reigning heavyweight champs in that musical ring and Chi was already a local hero, the guy you wanted to be friends with to establish your punk cred. Before he could make some wisecrack or snub Darren I stepped in front of him, shook his hand and said, ‘You guys were great.’

“Then Chi surprised me. Without saying a word, he knelt down and pretended to kiss both of Darren’s army boots, which is still the most original, and hilarious, compliment I’ve ever seen one musician pay to another. By the time he stood up, shook his hand and said, “Good show,” Darren’s smile had turned fluorescent enough to attract moths.

“Darren didn’t have a very long career in music and, suffering from all sorts of mental illnesses, he didn’t have a very happy life after that, but winning the public approval of the SNFU front man must have been one of the highlights.

“Except I don’t think it was Mr. Chi Pig who did that. No, that was my old skateboarding buddy, dishwashing partner and radio show co-host, Kenny Chinn, who did that.”

Blake Cheetah

Two sides of the SNFU singer on an early tour and towards the end of his life.

5. THE THIRD BUT NOT FINAL ACT

In the last act of most music documentaries either the musician makes a comeback or they die. The documentary, “Open Your Mouth and Say… Mr. Chi Pig,” takes the former route. At the end of the film, Chi is preparing for a 30th anniversary tour with the group.

But the film ended before the tour began. In truth, and I feel bad writing this, but it wasn’t as much of a comeback as many of us had hoped for. At that point, his voice half-shot, his aerial circus grounded, he was the only original member left in the group.

For the SNFU die-hards it still would have been great to see him up there again. The shows across Canada and Europe got decent turnouts. In Edmonton, over the course of some different tours, he got to reunite with former bandmates like Evan C. Jones and Jimmy Schmitz both in person and onstage.

Chi reunited with drummer Evan C Jones on comeback tour

Still, his big comeback fizzled. Even the group’s final album, Never Trouble Trouble Until Trouble Troubles You, released in 2013, seems like more of a footnote than a cornerstone in the band’s career. When he passed away at the age of 57 in 2020, his body broken and poisoned by too many decades of rock-hard living, he was way older than anybody in the so-called “27 Club” (Hendrix, Morrison, Cobain, Winehouse, et al). So the usual third act doesn’t work in Ken’s story.

On a wet night in Victoria, BC in late October 2020, Marc Belke and I stood on the patio of a craft brewery, holding beers in one hand and umbrellas in the other, while social distancing, as the silver rain fell like hyphens and commas past the orange streetlights.

Between us, we had some 40 years of catching up to do, swapping tales of skateboarding and basement jam sessions. By comparison, our future lives, careers and international travels seemed all the more incredible for the fact they were launched from such middle-class origins in a city like Edmonton, which is a hotspot of pretty much nothing. By extension, the rise of SNFU from a band playing makeshift bingo halls to a global mainstay of skate-punk and hardcore seemed all the more incredible too, and so did the story of Chi Pig. How did a guy singing off-key about breakfast cereal, roller skating and killer tomatoes in my mom’s basement become such an internationally acclaimed singer?

The story arc of his life seemed incredible – almost unimaginable. And that’s one of the main reasons why Marc and I came to a mutual decision over a few beers and much banter that, ultimately, Ken’s story is more triumphant than tragic. Here was a guy who overcame enormous odds and obstacles, who faced down racial and sexual discrimination, who rose above his poor and troubled home, who even conquered his demons for long stretches of time, to become one of the most original and beloved punk singers of his era. In concert with his songwriting partner Marc, and many other talented bandmates who also contributed to the sound and the songs, he helped to create a discography that continues to influence and inspire punk fans and musicians in equal measures.

That’s only half the story, though. We also shared some of our misgivings about his passing, which are common enough in such scenarios. Whenever a friend or family member passes away everyone has their regrets: the missed call that was never returned, the text message that went unanswered, the words never spoken, the fractured relationship never repaired.

In our case, it was the reunion that never happened. All my searches for him were in vain. The last opportunity I had to see Ken in person was finding a poster on a Vancouver telephone pole announcing his birthday party at a local punk bar in October 2018 – some three days after I had booked a flight back to the US.

As it turned out, the very last chance we had to hang out before that came in Montreal in 1990, when his new band The Wongs was coming through town. A mutual friend tried to organize a dinner for us, but I blew it off in retaliation for what I perceived as some overly egotistical behaviour on his part back in Edmonton. Who was the egomaniac then, asshole?

In our youth, little do we realize the long-lasting ramifications of those actions, which seemed so logical and justified then and end up looking so tragically stupid, vain and self-serving later in life.

Catching up with Marc “Muc” Belke in October 2020 in Victoria, BC.

When I was trying to track him down in Vancouver I wasn’t even sure that, if we did meet up again, whether we’d still even be friends or not. In the middle of putting this together, another old musician friend, who had no idea I was writing a tribute to him, sent me the transcript of a radio interview Chi had done with Nardwuar, a famous radio DJ and VJ in Canada, back in 2005 for CITR FM in Vancouver. At the beginning of the interview, Nardwuar told him that he had been playing a track from an old band of mine and Ken said, “Oh rad. The single I imagine?” Instead Nardwuar mentioned a compilation album from Edmonton called It Came From Inner Space that we both appeared on, a song called “Party’s Over by the Malibu Kens.” Chi said, “Oh yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah, I went to high school with the Malibu Ken that wrote that song and who turned out to be Blake Cheetah, who became the bass god for Jerry Jerry and the Sons of Rhythm Orchestra.”

It was cool to hear him still using skateboard slang like “rad,” never mind the rest of it. But I wonder why somebody would send me something like that in the midst of all this? Serendipity or coincidence? Synchronicity or something else? I don’t know. I’d rather not nail any of those doorways shut by insisting on a particular definition.

Chi with DJ and VJ Nardwuar the Human Serviette

Marc Belke shared a few of his regrets. “I wish I’d been a better friend to him, but when I left the band in 2005 our friendship had turned toxic. I was doing most of the work for the band and didn’t feel like I was getting any respect or cooperation out of him,” he says.

The group’s two main men did not keep in touch after Marc left, but they did have one final reunion at a punk show in Vancouver some five or six years ago. “I thought it was gonna be awkward ‘cause I heard he’d been talking a lot of shit about me, but it was fine. We just stood there and laughed a lot. He still had the same mannerisms and that great sense of humour. He could be an asshole but he touched a lot of people,” says Muc.

When I mentioned to Marc the anecdote about Chi kicking a beer Lisa offered him out of her hand, though I got some of the details wrong and misremembered that it was before a gig, which it wasn’t, Marc leapt to his defence in a nanosecond. “Hey, the guy was about to go onstage.” Then he smiled and, clearly joking, says, “Lisa should feel honoured that Chi Pig kicked a beer out of her hand.”

Some loyalties among ex-band mates do not die.

Brent Belke never reconciled his differences with the singer. After he left the group in the late 1990s they only bumped into each other at a few punk shows in Vancouver by Bad Religion and NOFX. Just the same, his passing did have an effect on the guitarist, who now makes a living composing music for film and TV. In a message, he writes, “Ken’s death didn’t come as a surprise, but it was strange when it happened. A sad empty feeling popped into my head and distracted me. This went on for days.”

Marc was not surprised to get the phone call either. “I’d been expecting it for years…. and I cried a few times later. We hadn’t been friends for a long time but we were still brothers.”

Ken’s life reached The End last July, but the posthumous chapters in the story of him and SNFU are still being written. In 2021, a five-song EP will be released of tunes the group was working on around the time of their 2004 release, In the Mean Time and In Between Time. Also slated for release this year is the first vinyl edition of the only album by Marc’s side project the Wheat Chiefs. Entitled “Redeemer,” the record also features SNFU members Brent Belke and bassist Rob Johnson, along with Edmonton vet Ed Dobek on drums.

The cover of the new five-song EP by SNFU featuring posthumous performances by Chi Pig.

Artists Lacey Jane and Layla Folkmann are pictured with their mural of Mr. Chi Pig in Vancouver.

Last fall, two Edmonton artists, Lacey Jane and Layla Folkmann, painted a mural of the late singer on the wall outside the Cambie, one of his favourite drinking spots in Vancouver. This year they are hoping to reprise the project in their hometown.

There’s also a regularly updated Facebook group called “All things SNFU and Chi Pig related!” which has some great content like this portrait of him by the artist, Trevor Phillips. Some members of the group think it’s the best portrait of Chi they’ve ever seen.

Trevor Phillips’ beautiful portrait of Chi.

Ken also left his friends and fans with a final farewell in the form of a song called “Cement Mixer (to all my beautiful friends).” True to his macabre wit, he sees himself reincarnated in a cement mixer to become part of the pavement. The slow tempo and acoustic vibe suits his well-rutted voice. It’s a classy and moving swan song.

There have been inklings of a book project that would collect many of Chi’s artworks and gig posters. I’ve also read some online rumours of fans lobbying for a statue of Chi Pig to be put up in Edmonton. Not sure what Ken would have made of that. Knowing him, he’d crack some joke about becoming an open-air toilet for pigeons and seagulls.

The statue would be cool in a weirdly ironic way: the former outcast who became a future pillar of the arts community. If I had any pull with the municipal authorities in Edmonton, I would ask them to erect the black marble and rose quartz statue in a skateboard park. The image would depict Ken balancing on one hand atop an enormous bass drum, his knees and running shoes tucked in over his head with a microphone in his free hand instead of a skateboard. Suspended in the middle of one final aerial and one last gig, he’d be defying gravity and all the forces trying to hold him down, as he did so often in his life and music career.

That’s how I’d like to remember him anyway.

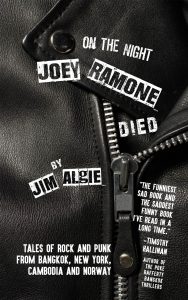

Jim Algie is the author of a number of different books such as “On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of Rock and Punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway,” which features some of his best music writing. The book is available on Amazon.

Great read Jim!

And your Mom’s quote was just the best…

Thanks man, It was a good read.

When I was asked to make Never Trouble I phoned Marc to ask him how he felt about it. Marc wasn’t super happy about it but gave his blessings. The recording was a bit of a mess but it was good to get Ken working again, to give him a leg up after all the trails blazed for all of us. Thanks for this.

Thanks, Steve. Records serve many purposes. Getting him back onstage and in the recording studio would have been great therapy for Ken.

Dearest Jim…

This is quite the most decent closest feeling well written about our Brother Kenny…

I love you for being the Man that you are with my deepest energy to be able to somehow get out this realistic care about our Friend…

I can only say my PEACE & LOVE does SHINE ON for myself, and for ALL OF US CRAZY DIAMONDS That are still here on this Plain…

Love…

ECJ…X~~~~0

When I ran into Kenny a few times visiting Vancouver, once at a NoMeansNo gig and other times at downtown bars, I’d always greet him as “Kenny” since that was the only name I ever really used. Amid a group of locals there I had a few strange looks from people who’d apparently never known him by that name. He explained: “only my friends call me Kenny.” I laughed when he said it but that meant a lot.

A great tribute Jim. It’s a perfect encapsulation of the mean yet hilarious nature experienced by those of us who knew or encountered him. Whether he had one foot on my head while singing about a gravedigger, or treating me to dim sum on a Sunday morning, time spent with Ken was always memorable. A shame you were not able to track him down. I was able to visit him at St. Pauls a few months before he passed, and gave him a photo of one of his classic leaps, taken at Eastwood Hall in ‘87. Like your statue idea, that is also how I will remember him.