Editors are the goalkeepers of the publishing world, saving many a writer from making heinous mistakes but most of the time they are overlooked. This ode sings their praises. It’s also a requiem for a veteran editor named Paul Dorsey.

During late October and early November the dead are feted at different festivals like Halloween, All Soul’s Day and, here in Mexico, El Dia de Los Muertos, which melds Catholic and pre-hispanic influences. One of the deceased who has been mourned by many in the Southeast Asian media scene is the veteran journalist Paul Dorsey, who had his life cut short by a heart attack in early September.

When I first met him at The Nation in the mid-1990s we were working on different desks. He was a sub-editor on the front desk. I was a copy-editor in the features section called Focus, where we had a running joke about erecting a statue to “The Unknown Sub-editor,” in the same spirit as the old war monuments to all the soldiers who died and never got their due. The image would depict a nameless, faceless editor slumped in front of a keyboard, his face obscured by the computer monitor, for this is one of the most thankless and depersonalized tasks in journalism or anywhere in the publishing world.

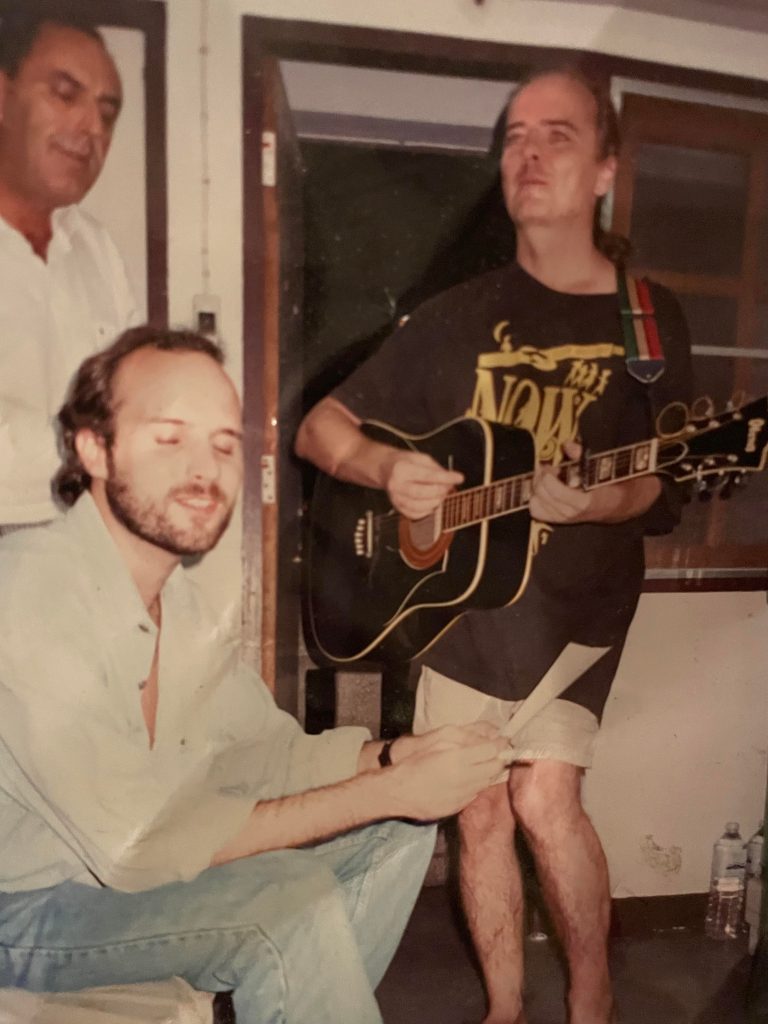

A couple of unsung editors singing the praises of Bob Marley via a cover: Scot Donaldson with the beard and Paul playing guitar. The other man is unidentified.

Sub-editors don’t get bylines. They don’t get much respect or any credit. By and large, they are paid a pittance. Here’s what subs get: grief and shit. Grief from prima-donna journalists who don’t want their precious copy changed, and shit from pedantic readers who want to call them to account for some trivial error. (“I’m writing to inform you that Volkswagen discontinued this car model in 1983 not 1981 as stated in your article.”)

Otherwise, the sub-editor spends his entire career in almost total anonymity; visible only to other journalists who read the masthead to see if they know anyone there who might give them work or buy them a drink. That’s unfair. These goalkeepers of the publishing world have saved every writer who has ever published in print or online from committing the most grievous and embarrassing of errors. Without their dedication to fact-checking and rewriting and upholding the laws of grammar, what you would have is, well, like so much of the internet today: a jungle of gibberish.

Paul Dorsey spent most of his life in those trenches, toiling for daily newspapers in his homeland of Canada, as well as in Bangkok, Hong Kong and Shanghai. No wonder he looked so browbeaten and hang-dog despondent sometimes. No wonder he developed a taste for the alcohol of amnesia.

Sub-editing is a gig that requires a great deal of knowledge about a great many subjects; it also requires the ability to juggle all of them while walking the tightrope of a deadline with no safety net. Paul was one of those all-rounders. His comprehensive knowledge of the arts often astonished me. After I posted a Hank Williams’ song called “Rambling Man” in a music group, the only comment came from him, “Did you know that was the only song he ever recorded in a minor-key?” No, I didn’t. Another time I posted a nineteenth-century oil painting of a cityscape in Glasgow as a Facebook cover photo. The only friend of mine who knew both the painter and the painting was Paul.

Unlike many subs, Dorsey enjoyed a more public life as a book reviewer. His tastes in books were as eclectic as his tastes in all the other arts. Sometimes he chose to review a literary novel by Julian Barnes or a history tome. Often he reviewed books by expat authors in Thailand or Thai writers who had been translated into English.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be rerunning as many of his reviews as we can find in the Bizarre Thailand group on Facebook. Some are still on the Nation website. Many, I fear, are gone forever. Five or six times I told the stubborn prick to get his books-and-music-and-more blog, “Dorseyland,” back online, but you can find it using the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/…/dorsey…/category/about-dorsey/

This was taken not long after Paul arrived in Bangkok in 1992.

In the meantime, if you want to do something to honour his memory and legacy then join the Facebook group he started called, “Thailand Expat Writer’s List,” and do a post now and then. Too often sloth is synonymous with not giving a shit.

The first book review I ever had to copy-edit at The Nation by Paul was a biography of Lou Reed by Victor Bokris. There wasn’t much copy-editing or subbing involved with any of his work. Paul wrote “clean copy.” He started the review with a long description of seeing Lou Reed live in Toronto. Paul detailed all his on-stage stunts, like tying the mic cable around his arm to simulate shooting up during “Heroin.” As a greenhorn, I didn’t know that you could put such personal experiences into an arts review. It’s a narrative stratagem that has served me well. Since then, I’ve used it dozens and dozens of times, but I borrowed it from him. During his lengthy career of 40 years, I’m sure he influenced many other writers and editors.

The first book review I ever had to copy-edit at The Nation by Paul was a biography of Lou Reed by Victor Bokris. There wasn’t much copy-editing or subbing involved with any of his work. Paul wrote “clean copy.” He started the review with a long description of seeing Lou Reed live in Toronto. Paul detailed all his on-stage stunts, like tying the mic cable around his arm to simulate shooting up during “Heroin.” As a greenhorn, I didn’t know that you could put such personal experiences into an arts review. It’s a narrative stratagem that has served me well. Since then, I’ve used it dozens and dozens of times, but I borrowed it from him. During his lengthy career of 40 years, I’m sure he influenced many other writers and editors.

I have heard many say that life is 10 or 20 percent what happens and the rest is how you take or process it. If that’s true, then death is the same deal.

Anyone who worked with Paul back in the 1990s knows that he survived a near-death experience around the end of the millennium, which could have easily gone the other way. After that he got sober for a long time. He moved to Hong Kong and worked for an English daily. At one point he relocated to Shanghai and worked for a paper there. Even after he returned to Bangkok, he and his former paramour – the bottle – remained on frigid terms for years. During that period of abstinence, I asked him once if he was going to quit smoking too. With that slow smile of his, Paul said, “Now that’s just crazy talk,” before lighting a smoke. In his low-key, self-effacing, quintessentially Canadian way, he could be very funny at times.

Dorsey was well aware that his accident had made him into a better person. In the last message I got from him, maybe 10 months or so before his heart gave out on him, he was trying to raise money for another expat journalist who had also been injured in Bangkok.

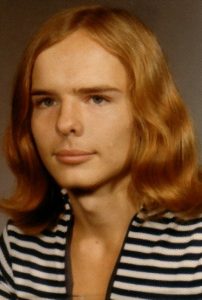

Paul Dorsey in 1971 as a high school student.

His loved ones may console ourselves with the fact that Paul got more than 20 extra years on earth than he might have had otherwise. He also got to enjoy a few years of semi-retirement from subbing after leaving The Nation.

In another silver lining he could not have foreseen or maybe even imagined, our old project is back on the drawing board, though the monument has been scrapped in favour of a portrait. The artist I’ve commissioned is depicting a figure slumped in front of a keyboard, eyes on a monitor. No longer anonymous, the figure bears more than a passing resemblance to Paul Dorsey. If there was any credit-where-credit-is-due justice in the publishing world, “Portrait of an Unsung Editor” would be hanging in every newsroom and publishing house on earth, as a thankful tribute to all the different subs, line editors, copy-editors, and rewrite men and women for their largely uncredited contributions to the written word and to upholding the truth in a world of misinformation and serial liars. That’s a dangerous task these days. As George Orwell wrote, “The further a society drifts from the truth, the more it will hate those who speak it.”

For an admirer of the visual and literary arts like Paul, I think he’d appreciate being reincarnated as both a portrait and a potent metaphor.

A bunch of Paul’s reviews are listed on this website.

Thank you for posting this Jim.

Don’t know why I never saw the post before now.

Anyhow, I had great pleasure meeting Paul a couple of time, the year before he passed.

When talking with him, you instantly felt he had this “know how”.

Such an interesting person.

Very well written Jim, Thnx a lot.

Rgds

Kai