After a convicted serial killer dubbed Thailand’s “Jack the Ripper” was released from jail in 2019 only to kill again, Jim Algie looks back at a true crime show from 2013 called “The Masseuse Murders” which chronicles his deadly exploits. The subjects interviewed for the documentary include the Thai policemen who worked on the case, prostitutes who worked with the victims, and the author himself, who provides background details on serial murder and the flesh trade in Thailand.

In early 2005 the body of a masseuse was found in an upscale hotel in Mukdahan, a city overlooking the Mekong River in northeastern Thailand. She had been strangled with her own bra before being drowned in the bathtub.

Over the next few months, the cadavers of more masseuses and karaoke singers turned up in other parts of the country, leading police to suspect that this was only the second case of serial murder in the history of Thailand.

The first such serial killer was See Ouey Sae Nguan, a Chinese immigrant who killed multiple people, mostly children, in Bangkok’s Chinatown and the eastern seaboard around Rayong province in the late 1950s, to feed off the spiritual power and courage said to be residing in their livers. This is an ancient black-magic ritual practiced by the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia, as well as the Japanese during their Chinese campaigns of the 1930s and World War II. In the “Chichijima Incident” in 1944, Japanese soldiers killed eight American airmen and cannibalized four of them. As a soldier in China, it’s possible that See Ouey had seen, or participated in, acts of cannibalism on the battlefield years before he arrived in Thailand.

Until he was given a proper cremation in 2020, his naked corpse, preserved with formalin so it turned cockroach-brown, had been on display at the Songkran Niyomsane Forensic Medical Museum in Bangkok for decades. The ceremony took place after an online petition stoked outrage about how he had been stripped of his dignity and may also have been a scapegoat in several other murders. Racism against Chinese was typical in Thailand back then, which I mentioned in the story I wrote about him in the non-fiction collection Bizarre Thailand (2010) and later in a noirish novella called “The Legendary Nobody” in The Phantom Lover and Other Thrilling Tales of Thailand (2014).

That’s why the Indian directors of a true-crime show called The Masseuse Murders contacted me to be an interview subject.

For the TV show, which originally aired on the Asia Crime Investigation channel, the producers also did a series of interviews with some of the investigating officers, who discuss how the investigation proceeded by catching a couple of lucky breaks. Since the police procedural does not exist as a genre in Thailand, either in crime reporting or crime fiction, because the police are a law unto themselves, these interviews provide some rare insights into their investigative processes.

The 50-minute show chronicles the killing spree of a conman erroneously dubbed “Thailand’s Jack the Ripper.”

BEHIND THE CRIME SCENES

In between the restaged murder scenes are clips of police file footage that show the crimes scenes, next to CCTV footage of the killer entering and exiting various hotels, with enough forensics to keep CSI buffs happy. That said, the “Jack the Ripper” tag he was dubbed with in the Thai press is inaccurate. Somkid strangled or drowned all his victims. He did not butcher them. The only real link to “the Ripper” is that they both targeted ladies of the evening.

In the interview clips, the director asks me some of the usual questions about Thailand on subjects like prostitution and more unusual topics, like the traits associated with serial killers, such as pathological lying (think John Wayne Gacy), the constant swapping of identities (think Ted Bundy), and the megalomaniacal delusion that they can never be caught (think Jeffrey Dahmer) which inspires more and more reckless acts that leads to their arrests.

Those parts are okay. After appearing in TV shows or documentaries I usually wish that I could edit my speaking bits later so they sound more clever or insightful. The art of the sound-byte is often lost on authors who are used to explaining their points over the course of lengthy essays or book chapters.

The aftermath of a hotel murder in northeast Thailand, recreated in the show.

For me, the real highlights of The Masseuse Murders are the interviews with the different women talking about their deceased friends. In Mukdahan, a colleague of the slain karaoke singer, Warunee Pimpabutr, talks about the difficult life she had led and yet remained such a cheerful and upbeat person,, while the owner of the bar, Imchit Paklau, talks about how Warunee, just 25 at the time of her death and the only person in her family with a job, worked there to help support her parents and five siblings. In the boondocks of the northeast, which breeds most of the country’s factory workers, taxi drivers and sex workers, her younger siblings had to walk several kilometers to school every morning. At the time of her death, she was saving money to buy a motorcycle for them so they could drive to and from school.

Far from being portrayed as passive victims, these women are framed as fighters and survivors. During a police reenactment of one murder, the serial killer Somkid Pompuang was attacked by a female colleague of the slain woman. With steel in her eyes and ice in her voice, Imchit says in the show that Somkid got the death sentence that he deserved.

It’s easy to glorify, or to moralize about the sex trade in Thailand, but the reality is more banal. “I spend so much time with these girls that I know nobody is here by choice. They do it for their parents and siblings. So please be sympathetic,” says Imchit.

Writer and director Mayurica Biswas took that advice to heart.

The complete true crime show about Thailand’s second serial killer is up on Youtube.

DEBASING THEIR VICTIMS

Friend pays tribute to a wife, a daughter, a sibling and victim of this serial killer.

Serial killers are notorious for debasing their victims in some way, either physically or emotionally, or through sexual acts like sodomy intended to make these marginalized characters feel superior to those they rape and slay. So many of them, like the Green River Killer in Seattle or Vancouver’s Robert Pickton, target prostitutes because they are more vulnerable to predation.

The pursuit of power leads killers like Somkid to use their bare hands as fatal weapons. Then they can feel the victim’s pulse throbbing in their throats, savor the fear in their eyes, watch their death throes cease and their bodies go limp.

In the act of killing and raping they have the godlike powers of life and death – powers they have so often been denied in their lives lived on society’s margins, like this chronic scammer pretending to be a talent scout for a big music label, among other guises, whose death sentence was commuted to life in prison back in 2005 for murdering five women.

Best of all, The Masseuse Murders, which bears the fingerprints of a woman’s sure-handed and sympathetic touch, goes a long way to restoring the dignity of the women who died at the hands of this remorseless serial killer and chronic conman.

It’s too bad the prison authorities who let him out of jail in May 2019 for good behaviour, after he had only served 14 years in jail, did not see this movie. If they had, they would not have considered clemency and a 51-year-old lady in Khon Kaen province would not have been murdered later that year by Somkid, who became the subject of a countrywide manhunt.

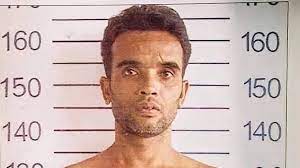

Telltale scar of a serial killer

Acting on a tipoff that Somkid had disguised himself as a monk and was trying to escape into Laos, the boys in brown began checking all the cars and buses waiting to cross the border at Nong Khai. That tip led nowhere, but the next lead was more promising. On a train, a female passenger, who was not identified for security reasons, noticed that the passenger sitting across from them had a scar over his eye that looked like a dead-ringer for the one she’d seen in the mug shot of the serial killer on the wanted poster. The couple changed seats. She relayed her suspicions to her boyfriend, who then took a sneaky photo of Somkid that he sent to the police. At the Pak Chong station they boarded the train to arrest him.

In 2020, he was sentenced to death again. This time he deserves to receive the same amount of mercy he showed to his victims, which is to say none.

I sure look a lot better in pixelated images taken from an age-concealing distance. Photo by Mithran Somasundrum.

POSTSCRIPT 2022: DAY OF THE DEAD IN MEXICO

Stories like these don’t stay in the headlines for very long, but they do come back to haunt us in different ways. Quite honestly, I hadn’t thought of him since updating this story in 2019 after they rearrested the serial strangler. Like Ted Bundy, who escaped from prison in Colorado to go on his most vicious killing spree ever in Florida, these kinds of killers can never be rehabilitated. That’s another thing I discuss in The Masseuse Murders, calling him, in what could be the chorus of a blues song, “born to be bad.” Indeed, in the Thai press, they recounted stories of how Somkid started stealing at the age of eight. A few years later he was expelled from school for stealing a teacher’s bicycle.

For the victims’ families and, to a lesser extent, for those of us who report on them, The End of these stories never comes. On November 1st, the Day of the Dead in Mexico where I live, an old friend’s wife was watching the show on Thai TV. She told Mithran. He took a screenshot and tagged me in a post on Facebook. The nightmare begins anew.

Coincidence or not, it does seem odd that this happened on the exact day when the spirits of the deceased are said to return to earth. Silent and invisible, these wandering souls are supposed to manifest themselves in sudden gusts of wind and Mexicans claim they can extract the “essence” of any offerings, like favourite meals and tipples, left for them on makeshift altars adorned with marigolds, colourful skulls made out of sugar and photos of the deceased. It’s quite similar to some of the Chinese rituals of ancestor worship.

Far from being a solemn festival, as one might expect, the air hums with the electricity of joy and music, as Mexicans demonstrate how their love for family and friends has not died along with them. in the early evening, parades take over the streets in towns and cities all across southern states like Oaxaca, the festival’s spiritual homeland, in a twinning of indigenous and Catholic beliefs. The two main dates of the festival are November 1 and 2, which are All Saint’s Day and All Soul’s Day on the Catholic calendar, when the dead return to the lair of the living. Yet the followers of the latter faith might well be shocked by the marching bands winding through cemeteries beautified with flowers and illuminated by flowers. One man offered me a shot of Mezcal. Another man gave me a beer and showed me the tombs where his mother, father and siblings were buried. Behind the cemetery was a raucous party in progress. A Grim Reaper strode around on stilts. Children dressed as superheroes and skeletons danced and played while their parents took videos of them. A group of college-age guys dressed as white rabbits with eerie lights on their faces waltzed through the crowd waving gigantic carrots. In the south of Mexico, and in places like Tucson, Arizona, which has a huge Latino community, the most common sight are the people who have their faces painted to look like skeletons. The women wear marigolds in their hair. The men often wear suits. Known as calaveras, which can refer to both a skull or an obituary, these celebrants embody the belief that death is the ultimate democracy; all are equal in this final state of decomposition. Since we’ll all die one day, it’s better to enjoy life while we can and have a fiesta to rouse the dead. That’s the Mexican take on these matters of mortality. And I find it rejuvenating. Instead of making death a taboo topic, let’s bring it out in the open to make it less frightening, and celebrate the lives of our loved ones who are no longer alive.

On my own altar, where I have laid out special offerings for family and friends, I welcomed six more spirits this year, namely, the Thai women who endured hard-as-hell lives and suffered painfully premature deaths. One of them was saving up money to buy a motorcycle for her siblings so they wouldn’t have to walk several kilometers to and from school every day.

Ladies, I hope you enjoyed the food and drink. You’re always welcome at my altar.

Recent Comments