The recent death of my cat in a freak accident left me feeling both inconsolable yet unable to express the enormity of that loss to myself or anyone else.

Words by Jim Algie

After his passing, I decided not to make an announcement on social media. I’ve taken that route before, and it’s a dead end. I know that people mean well, but all the repetitions of “Sorry for your loss,” “Thoughts and prayers,” “RIP” and other condolences, provide little solace and zero insights into either the nature of mortality or the grieving process.

As a writer and editor by trade, I tend to use books for companionship in times of distress. Last year, after a few old friends passed, I read Joan Didion’s much-lauded memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” which deals in part with the death of her husband and fellow writer, John Gregory Dunne. After he died of a heart attack, she noticed the “unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaningless itself.”

As a writer and editor by trade, I tend to use books for companionship in times of distress. Last year, after a few old friends passed, I read Joan Didion’s much-lauded memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” which deals in part with the death of her husband and fellow writer, John Gregory Dunne. After he died of a heart attack, she noticed the “unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaningless itself.”

I can relate to that. Death drains our usual interests of meaning as surely it bleaches all the colours from our world. It forces us to question our most long-held assumptions and beliefs in work, love and hobbies, to find them wanting or devoid of comfort and meaning.

Our fear of death can also strain personal relationships to the breaking point. On the night when we rushed my cat to the vet in Tucson, Arizona, Rhishja and I were standing by for updates and X-ray results, when I started sniping at her about the high cost of veterinarian care in the United States, which precipitated an argument.

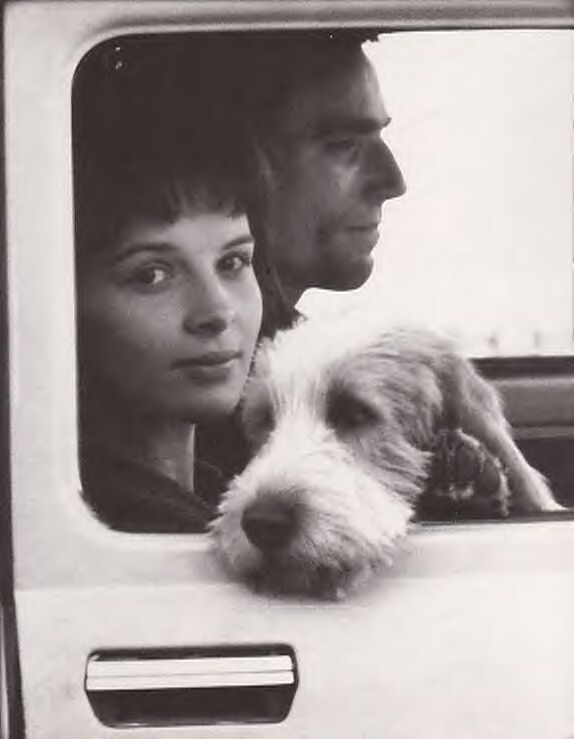

In the wake of his death some four hours later, after the sobs shook us by our spinal cords and the cloudburst of tears dried up, we lay on the bed, holding hands but saying little. A scene from Milan Kundera’s masterpiece, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, came back to comfort and trouble me. Toward the end of the book, when Tereza and Tomas have to put their dog to sleep, they realize that they are mourning different versions of the same animal.

In our case, it was true. Our memories of this feisty feline, who reminded me of the green-eyed protagonist in the “Black Cat” by Edgar Allan Poe, are very different. He played different roles in our lives and we had different nicknames for him. Sharing any of those different reminiscences would have made us even sadder than we already were. In the weeks that followed, we were careful to skirt the subject of his death, as if tiptoeing around the edge of a vast abyss in the middle of the night.

Scene from the excellent film version of Kundera’s novel, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliet Binoche, with the dog that both unites and divides them.

NOTES ON THE PASSING OF PETS

Why does the death of a cat or dog cause people so much grief? In the absence of any scientific studies on the subject, I can only guess that most children’s first experience of mortality comes from the passing of the family dog or cat. All those poignant questions we first asked ourselves as kids – Where did he go? Can I see her again? What did his life and our friendship mean? Why couldn’t I save him? – which caused so much sorrow and soul-searching back then are just as troubling and unanswerable in adulthood.

There is an upside to this story, too. The need to rise above that death by giving one’s heart to another creature some day, strikes me as one of the very few instincts that not only survives adolescence intact, but also serves as a GPS for navigating future friendships, which may collapse in time, or the ups and downs of romances that blossom and wither.

For me, the book that best captures this bittersweet dichotomy is “Old Yeller” by Fred Gipson. It’s a children’s book with adult themes and characters that I read as a boy. The fact that a novel from 1956 is still in print today proves that there’s something age-proof about this tale of a rural family in nineteenth-century Texas, who adopt a stray dog they name Old Yeller for his yellow coat and distinctive howl.

In all the tales of people and their pets, is there a sadder scene than after the dog, defending his new family against a rabid wolf, gets bitten and has to be put down? For an ending, tempered with just enough plausibility to seem believable, is there a final chapter more heart-rending than the boy inheriting one of the puppies sired by Old Yeller?

Poster for the movie version which sticks quite closely to the book.

POINTS OF REFERENCE

When we’re lost in grief, stories provide welcome distractions and compass points to find our way back to our normal selves. Yet their power to preserve life is nonexistent.

In truth, I am not really sure how my cat died. When Rhishja heard his agonizing howl she ran into the laundry room to see him sprawled on the floor, his limbs splayed at odd angles, foaming at the mouth.

The X-rays the staff took at the animal hospital and emergency center showed that he had suffered heavy chest trauma and there was some inflammation in his lungs. The vet said it looked as if he’d been in a car accident. How did this agile and surefooted creature fall from his perch onto the floor? He might have had a stroke. That’s one possibility. When cats have strokes they can lose their balance and fall. One cause of feline strokes, I read after his demise, is kidney disease, which turned up as smudges on his X-rays. It’s also possible that he may have suffered from vestibular disease that can cause a loss of balance, too. Many cats recover from that illness in a few weeks but not if they’ve had a terrible fall like he did.

Since we did not have a necropsy done before his cremation, the real catalyst of his death will remain unknown. All I can say for certain is that when he fell it was around 8pm, just before I finished my online tutoring for the night. In preparation for our playtime he would sometimes jump down on the floor and be waiting for me, shrugging off his nap by arching his back and stretching the cramps out of his front legs.

So it’s hard not to feel a little complicit in his death. Guilt, resistant to reason, is one of the most haunting and relentless of emotions. Some of the ghosts in the classic tales of terror by Shirley Jackson and M.R. James are born of such guilt, and some of those specters drive the haunted to madness, or murder, or early graves.

So it’s hard not to feel a little complicit in his death. Guilt, resistant to reason, is one of the most haunting and relentless of emotions. Some of the ghosts in the classic tales of terror by Shirley Jackson and M.R. James are born of such guilt, and some of those specters drive the haunted to madness, or murder, or early graves.

To keep the guilt at bay, I repeat a mantra from the Travis McGee thriller, A Purple Place for Dying, by John D. MacDonald: “Remorse is the ultimate form of self-abuse.”

That might be true, but it doesn’t always help, for the human mind is the most cunning of con artists. It deceives us with false hope, it justifies our most self-serving actions, and it can easily swerve around self-lacerating guilt to arrive at happier outcomes. For the first few weeks after his passing, I wondered, What if it was just a stroke or vestibular disease and he hadn’t fallen? Would he have made a full recovery?

These are examples of what Joan Didion calls “magical thinking” in her memoir. After her husband’s death she refused to give away his clothes and shoes – because what was he going to wear in the future? That’s why I am tempted to classify bereavement as a “state of temporary insanity,” but wary of sounding like a sleazy lawyer, conniving a flimsy defense, in a legal thriller by John Grisham.

He loved to perch on top of my fridge in Bangkok beside the Godzilla statue.

Rhishja takes Yak for a “scoop and loop” at my old house in Bangkok.

THE TUCSON CEMETERY FOR PETS

Lately, I’ve been making regular trips to the Pet Cemetery in Tucson. It’s a beautiful and peaceful place near a 20-mile bike lane I like circumnavigating called “The Loop” that runs alongside a dry riverbed with a northern exposure of mountains as grey, knobby and ancient as the lizards that dwell there.

Simple inscriptions on the gravestones such as, “Our little girl” and “My best buddy,” say so much in so few words. More than a few mourners have given their cats and dogs the family’s last name. One lady was even buried in the same plot with her pets. The longest epitaph I’ve seen there is my personal favourite, because it sounds like the chorus of an old country song: “If tears could build a staircase and memories a lane, I’d walk right up to heaven and bring you home again.”

Gustav Flaubert: the writer with a grave heart.

I will not be interring my boy here. He’s already buried in my heart, alongside the other cats and dogs, friends and family members, I’ve loved and lost – whom I still love and still find in memories and dreams sometimes. As Gustav Flaubert wrote, “How we keep these dead souls in our hearts. Each one of us carries within himself his necropolis.”

But the author of “Madame Bovary” never knew my cat. Neither did Joan Didion or John D. MacDonald. During this painful juncture, stranded somewhere between the isle of grief and the shores of resignation, I’ve held onto their words and insights like lifelines to keep from sinking into the deep blues. What they have to tell us about the nature of love and loss are universal enough, but the reasons why every such life is irreplaceable are found in the particulars.

I have never read a story or seen a movie where a group of neighbours find a black kitten who has fallen out of a tree and landed on the spire of a Buddhist shrine, piercing his stomach and impaling him. That’s how we found this guy in Bangkok. Quickly we rushed him to the local vet. The vet stitched up the gaping wound in his chest, leaving him with a permanent six-inch scar. Eventually, his fur grew over it and formed a ridge.

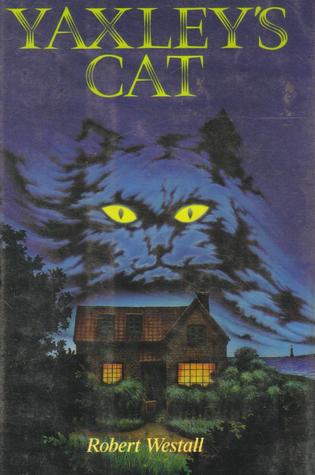

My neighbours’ Thai-British daughters, who were reading a children’s book at the time called “Yaxley’s Cat,” gave him the unusual name “Yaxley.” Thai people tend to pronounce x’s like k’s, so they called him “Yak” for short, which is the name of a giant in the country’s mythology: an appropriate moniker for such a small creature that was fearsomely territorial and regularly scrapped with male cats much bigger than him.

The children’s book that spawned his name.

He had a friendly and kittenish side, too. Until the second last night of his life he would jump up on my chest while I was sprawled on the sofa watching TV after work and lay on top of me for 20 or 30 minutes of petting. His heart drummed against mine. His blood warmed mine. Our eyes locked, and our breaths merged.

I’ve been on many hiking, camping and wildlife-spotting trips. I’ve explored coral reefs, rainforests and river valleys all over the world. But the nights with this half-feral creature perched on my chest like a miniature sphinx are the closest I’ve ever felt to the beating heart, breathing lungs and flowing life force of Mother Nature.

Our pets are the missing links between ourselves and the natural world. They are the go-betweens that remind us of our better natures (to care, to love) and our most savage instincts (to lust, to fight). It’s one of their most remarkable powers, and it’s one of the many things I will miss about that guy.

I have to remind myself not to get too gloomy. The cat and I did have seven great years together that created a cache of memories, photos and videos, which will long outlive him. For a stray kitten from  Bangkok, transplanted to Arizona for the past two years, he had a pretty good life.

Bangkok, transplanted to Arizona for the past two years, he had a pretty good life.

Rhishja, who has worked with dogs for many years, summed up the whole tragedy of this premature mortality by saying, “Compared to people, the lives of our pets are just so short.”

The grieving process is messy and convoluted. It’s a constantly changing weather pattern of clouds and downpours interspersed with periods of calm and sunshine. In “Flaubert’s Parrot,” Julian Barnes writes that one emerges from this period of mourning not like a train coming out of a tunnel but a “seagull coming out of an oil slick. You’re tarred and feathered for life.”

I hope he was exaggerating a little for poetic effect.

I don’t know how the next chapter in our life story will unfold, except that Rhishja and I will have to collaborate on this narrative of recovery and, as Kundera noted, both alone and together.

My cat hunting for squirrels scampering across the branches of mango trees in Bangkok.

The cat climbs his first mesquite tree in Arizona.

The last photo that Rhishja ever took of Yak, sitting beside his favorite playmate, Tupelo: a pair of rambunctious boys.

Memorial wind chime for Yaxley hanging in our backyard in Tucson.

Beautiful and touching. Thank you.