As a journalist who covered the first wave of the disaster and went back for many subsequent visits to write about the recovery efforts and the survivors coping with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Jim Algie looked back on the 10th anniversary of the Asian tsunami in 2014.

Like many other people around the world, I first saw the breaking news from CNN flash across the screen above stock market reports and sports scores scrolling past on December 26, 2004. It was Boxing Day, which surely must be named after the bruising and debilitating hangovers that one experiences on the morning following Christmas: the least auspicious time for a natural disaster to strike, catching many travelers unawares as they dozed in bed or walked woozily around buffet tables.

As good luck or sheer accident had it, I was supposed to have been holidaying at Lake Toba in Sumatra. I couldn’t make it but a friend and his wife had gone ahead anyway. The maps on CNN showed the epicenter of this underwater earthquake was just off the coast of northern Sumatra. The tremors of fear worked their way out through my fingers causing many typos while I wrote a brief email to make sure they were okay, then returned to watching the news with the kind of mounting dread that tunnels into your stomach and squats there like a tumor.

Photo tsunami-stricken youth Salahul Bain from the Insight Out Project

For the first few hours after the 10 metre-huge waves spread across the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean bulldozing everything in their path, the news networks repeated the same jerky, video-cam footage shot by tourists of water inundating shorelines and hotel lobbies; upending automobiles; turning streets into swimming pools and swimming pools into aquariums, as people shrieked and ran. At first it seemed small in scale, only a few dozen reported dead and maybe a few hundred injured. But every hour, as reports flooded in from half a dozen different countries (Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Malaysia and the Maldives) the body count surged. Nobody, not even the TV news networks or government agencies, knew what was really going on, nor that this would turn out to be the third largest earthquake ever recorded.

The situation was still shambolic a few days later when I accepted an assignment from a tourism body to visit southern Thailand to assess the damage and write a report that would hopefully reassure overseas visitors, little realizing that the grim ramifications of the task that would come back to haunt me for the next decade.

The first familiar face I saw while walking along Patong’s Beach Road, where the smaller hotels were as empty and gutted as haunted houses, after the waves trapped and drowned dozens of visitors dining at basement buffets, was a stringer for one of the better British newspapers. Her first piece about the aftermath on Phuket had just been published. In paragraph 15 she had written a sentence or two about how a few sex workers had returned to Patong and that the jet-skis were buzzing again. Her editor had entitled the article, “Prostitutes and Jet-Skis Return to Patong.” She shook her head and laughed. “Tabloid journalism at its tackiest. Thousands of people are dead and they’re playing up the titillation factor.”

This was the first act in a theatre of absurdities that the media directed and enacted. Their shoddy coverage, factual errors and lack of ethics still rankles some of the expat residents on Phuket. Sue Ultmann, the director of communications for the Baan Rim Paa Restaurant Group, said, “One of the senior reporters for a major news network was staying in a big hotel with her entourage and she wanted to shoot one of her segments with a pile of rubble in front of the hotel for a backdrop. She was furious that they’d removed the rubble. It’s a shame we didn’t ask her to pay 1,000 baht per person to bring back the rubbish as they could have used the money and I’m sure she would have paid.”

The press quickly muddied every welcome mat up and down the Andaman Coast by running the same photos and same video clips over and over again, by their constant scaremongering about the imminent outbreaks of epidemics (which never happened and they never accounted for), while spreading a number of tall tales like the one about the fish being served at upscale seafood restaurants around the Andaman area which had allegedly fed on corpses. (That apocryphal tale was later traced back to a Thai tabloid.)

Soon enough, Sue said, the word went around the tourism community, “Do not talk to the media.”

When journalists cover natural disasters they apply the same boilerplate and the same five or six angles: scientific, environmental, fiscal, political, celebrities arriving and a few standard-issue, human-interest features, such as following a survivor or relative searching for family members caught in the maelstrom.

Two weeks later most of the media had flown off like vultures to circle the next series of cadavers, leaving the biggest question unasked and unanswered: How do the survivors and the bereaved cope with what has been the biggest natural disaster of our lifetimes, claiming some 250,000 lives and triggering other earthquakes as far away as Alaska?

This photo and the opening shot were taken by Myo Min Naing for the Insight Out Project.

CROPPED FROM THE BIGGER PICTURE

The majority of the big news networks, wire services and international magazines limited their coverage to white Westerners; other ethnicities barely merited a mention. But these sins of omission also catalyzed some serious humanitarian endeavors, like the Insight Out Project: a sounding board for the voiceless and a creative outlet for the children who lost homes and/or family members. Many of these orphans were suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, a treacherous and difficult-to-diagnose malady. (As Sue Ultmann said of the aftermath, “We were in shock but we didn’t know we were in shock.”) Started by the Japanese photojournalist, Masaru Goto, along with his wife Yumi, a graphic designer by trade and an altruist at heart, they began giving free workshops in digital photography and journaling for young people in Banda Aceh, the most obliterated part of the region, and in Phangnga province, Thailand’s most heavily inundated area, where some 6,000 people died.

May May Lae frames the hope and apocalyptic desolation.

Some of these images are more effective than those taken by the hard news photographers, since they focus on starker and more personalized subjects that also show the ground-level realities faced by the majority of the survivors and PTSD sufferers, who were cropped out of the big mass media picture in favor of rich tourists from wealthier countries. May May Lae’s chiaroscuro of a building’s black skeleton juxtaposed against sunbeams fanning out from dark clouds is almost biblical in its depiction of faith and apocalyptic destruction. That balancing act also illuminates Prinya Varak’s image of a boy silhouetted against a lake and setting sun, whereas Myo Min Naing stares down hope in the midst of desolation by picturing a small tree that has survived the onslaught and is framed by the pillars of a gutted building. Filmmaker and long-term Bangkok expat, Jeanne Hallacy, who is also the executive director of the project, said, “The tsunami did not only wipe out people, homes and livelihoods, it also washed away childhoods.” That is the focal point of Myo Min Naing’s shot of a doll abandoned on a beach.

Many professional photographers also lent their talents and visions to the project, taking their pupils to shoot at atypical settings, like a construction site where migrant laborers from Myanmar live in metal shacks with no running water or electricity and, similar to the two young men from Myanmar sentenced to death for the murder of a pair of British backpackers on Koh Tao, but widely believed to be scapegoats, are dangerously vulnerable to exploitation. As photographer Suthep Kritsanavarin said, “You can’t understand how important it is to be able to speak out unless you have spent your whole life being ignored at the bottom of society.”

What emerged from these photography and journaling sessions was a series of portraits of Southeast Asian youth not glimpsed through the usual lenses of teachers, politicians and aid organization staffers, but through their own eyes, raw and unfiltered. That is a rare and important distinction. At the launch for the 2006 exhibition of the children’s work at the Foreign Correspondent’s Club of Thailand, Jeanne said, “It wasn’t really about the tsunami. It was a window in which these kids showed us what they wanted to say about themselves, their families, their dreams.”

Emboldened by successes like that exhibition, the project has continued on, though they are chronically underfunded and still need donors, staging other workshops for children affected by the violence in southern Thailand and more recently for youth turned into internal refugees thanks to the ongoing fighting in Myanmar’s Kachin state.

Another project that has endured far beyond its inception after the tsunami is the Phuket Has Been Good to Us Foundation. Originally started by Tom McNamara of the Baan Rim Pa Restaurant Group, who passed away from prostate cancer a few years later, the NGO sprang up to take care of what was a

Bodhi Garrett of Andaman Discoveries with his wife and their child

common problem in post-tsunami Thailand: big aid projects that never quite got off the ground. In this case, it was two completely destroyed schools in Kalim and Kamala rebuilt but without any English classes. The foundation stepped in to offer English teachers and classes that give the young, mostly disadvantaged learners a better chance at finding careers in a tourism-based economy and a dormitory for those orphaned by the tsunami or who came from broken homes, so that there are now 130 students, ranging in ages from six to 18, staying there and a thousand students partaking of the classes.

Sue Ultmann, chairwoman of the board of managers, preferred to emphasize the positive repercussions of the catastrophe. “We never had ambulances until then on Phuket and there wasn’t really a blood bank either. Enormous changes have come out of the tsunami. That’s what we like to highlight with the foundation.”

But positive stories hold little appeal for the mainstream media, unless the good Samaritans are celebrities. Yet, when you talk to those who helped to rebuild the region, like Bodhi Garrett, the stories they spin are often of a more constructive and hopeful nature. He put together a not-for-profit organization called the North Andaman Tsunami Relief that morphed into Andaman Discoveries, specializing in responsible and community-based tourism in Phangnga province. “Disaster relief lays down the foundation for community development for both a physical and social infrastructure. There were actually three tsunamis: the wave, then the influx of cash and assistance, and then the withdrawing of that assistance in the first to four years. Our approach was that you need indigenous solutions to indigenous problems. You can’t enforce this outside model of development because it will fail. Tourism was just a tool to empower the villagers because their traditional ways of life, like fishing, were already dying before the tsunami,” said Bodhi.

His company has gone on to notch up some big local and international awards for their devotion to responsible tourism and conserving cultural heritage. To what does Bodhi attribute his success? “I didn’t know how to do this when I started, but I had awesome Thai folks to teach me. My moxie was Western, but the method was Thai.”

Prapatsorn Navara of the Insight Out Project captures one of those images that haunts survivors

CLOSURE ON THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE ASIAN TSUNAMI

After 9/11 and the tsunami, or almost any traumatic event, the word you hear the most often is closure. There is no such thing in the view of Tew Bunnag, author of the short-fiction collection After the Wave. He worked down south on a Human Development Foundation project for Aids patients, last in line for assistance after the calamity. On and off, over two years he worked down there, striking up friendships and amassing material.

The first tale, “Lek and Mrs. Miller,” was commissioned by the BBC’s Radio 4, which wanted to broadcast different works of short fiction from authors in each of the affected countries. It’s a subtle story that builds to a gentle climax when a grieving Englishwoman and a Thai hotel worker come together to comfort each other. The story testifies to Tew’s belief that the “tragedy was a leveller. There were no more barriers, just people joined by their pain and hence by their humanity,” he wrote in an email.

Perhaps the standout tale in his collection, reprinted by River Books in 2015 and featuring black and white photos from the Insight Out Project, is called “Closure.” It stars a gay couple supposed to holiday together in Phangnga province, except Charoon’s jealousy and insecurities prevent him from leaving at the same time as Sueb. Only a year later does Charoon, still grappling with his guilt, visit the resort where his partner stayed before he was killed. “He realized that this need for closure was fictional, a device to round off a story or a film. In reality there was no ending to anything and his grief could not be healed by any formal gesture and that true forgiveness would require much more than scattering ashes in the sea and mouthing a few prayers. He had to make the choice of going on or of drowning.”

The will to live resurfaces when Charoon finally takes a new lover a respectful 18 months after Seub’s death.

Another barrier that stands in the way of closure, for those of us who were there, was the sheer horror of the scenes unfolding at places like Wat Yanyao in Phangnga province, where Dr. Pornthip Rojanasunand and her team worked for 40 days straight to identify some 5,000 cadavers

Dr. Pornthip led a team of volunteers to identify more than 5,000 corpses

laid out in a makeshift graveyard on the temple grounds and covered with dry ice to keep them from decomposing too quickly, so an eerie mist floated over the dead and sometimes you’d see chickens pecking at the eyes of corpses before the monks and forensic workers chased them away. Those scenes are imprinted upon our memories in the indelible ink of tattoos. Over time they have darkened and blurred, but they will never fade away entirely. When the TV news networks do their 10th anniversary stories – read: two-minute clips – this year none of those scenes will be included.

Nor will the fact that after cadavers have been in the water for five or six days it’s hard to tell whether they are Asian or Caucasian, or even male or female. Due to a phenomena that forensic scientists call “skin slippage” facial features are almost completely unrecognizable. So you have to look for tattoos, wedding rings, scars and piercings, or use DNA samples and dental records.

By far the most disturbing incident that I experienced personally came when I was helping a Scandinavian woman looking for her teenage son in the middle of these rows of bodies. We were bending over another blob of blackened, misshapen flesh when the corpse started moaning. Imagining some zombie coming back to life, we ran over to talk to Dr. Pornthip who explained to us that when gases escape from a decomposing body they make the vocal cords vibrate and the dead appear to speak.

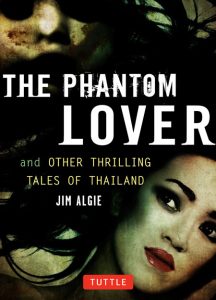

I used that incident more or less word for word in the concluding novella, “Tsunami,” from my short fiction collection released earlier this year, The Phantom Lover and Other Thrilling Tales of Thailand.

You see, I also needed to close a chapter of my life which has now gone on for the past decade. As it turned out, the friends I was supposed to visit Sumatra with were fine. The report I had to write for the tourism body was not; the boss lady forbade me to mention the tsunami even once. That’s a mighty big whitewash. It does tend to weigh on one’s conscience.

So I kept returning to the south, interviewing more survivors, hearing about their ongoing phobias and traumas, writing stories about the anniversaries and the more memorable rituals to honor the dead. On Phuket, for instance, the authorities released more than 5,000 lanterns to give all those lost souls a Thai-Buddhist sendoff as monks chanted on a beach turned phosphorescent by moonlight. In 2014, on the 10th anniversary of the Asian tsunami, there were many other commemorative ceremonies.

“Tsunami,” the closing novella in my short fiction collection, spans more than 40,000 words and took nine years to write and research.

In the final novella, spanning some 42,000 words in my book, the French-Canadian writer concludes that there is no possible way he can do justice to such an enormous tragedy that impacted so many lives in so many different countries, but instead of all the different journalism angles he has seen or used – political or environmental, spiritual or scientific, fiscal or touristic – he decides to jettison them all in favor of a more humane touch while standing around in the deserted Phuket International Airport at midnight where the walls are filled with photocopied posters – “paper ghosts of the missing presumed dead.”

Yves writes: “In the end, it wasn’t all that important what any of the deceased did for a living, what kind of cars they drove or what grades they got in school. Whether they were accountants or policewomen, travel agents or investment bankers, most were easily replaced in their workaday lives, as we all are when our time comes, which could not be said for the pivotal parts they played in any number of domestic scenarios as wives and sons, sisters, lovers, fathers. Their absences would be most sharply felt during family reunions on national holidays, at birthday parties in living rooms and at anniversary dinners in fancy restaurants lit by candles and smiles floating in the darkness, and during the photo sessions following graduation ceremonies when the missing person popped up in everyone’s mind but not inside the frames of any photographs.

“All the dead had been loved and that was their greatest legacy. It was why their lives mattered and why their deaths would be mourned by their loved ones for many years to come.”

This story originally appeared in The Magazine of the Bangkok Post in December 2014. It was updated in 2017.

Launching hot air balloons to honor the dead. Photo by Victor Snepts.

Recent Comments