No two books about prostitution in Asia have created so many imitators and detractors as A Woman of Bangkok and The World of Suzie Wong, or inspired so many appalling memoirs about Bangkok bargirls, writes Jim Algie, in a review originally printed in the Bangkok Post’s Sunday Brunch magazine. The review appeared in 2012 when both of the books were reprinted.

Years before the obscenity trial that allowed Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer to finally be published in America which, along with Playboy magazine and Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, helped to bring sex in from the margins of pornography to the bedrooms of suburbia, two British authors enjoyed scandalous successes by exposing the brothels of Hong Kong and Bangkok bargirls.

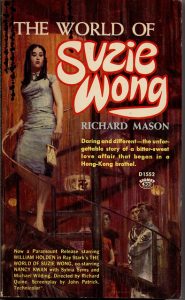

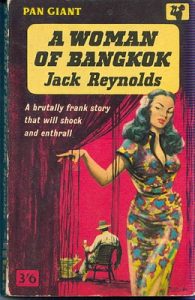

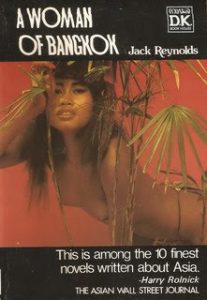

Originally published in the mid-‘50s, Jack Reynolds’ A Woman of Bangkok and Richard Mason’s The World of Suzie Wong have been recently reprinted by Monsoon Books and Penguin, respectively. As pioneering works of sexology and cross-cultural relationships, their influence looms large and their progeny is legion.

The two biggest influences on the hackneyed memoirs about Bangkok bargirls.

Reynolds’ novel laid down the template for all the half-cocked, vanity-press memoirs written by wayward Romeos, which should usually be subtitled “How I Lost My Heart, Sense and Savings to a Scheming Bargirl”. The most startling difference between him and his many emulators is that Reynolds was a real writer. His descriptions of dreary England, the narrator’s stuffy family background with a vicar for a father, and the prudishness of his relationship with Sheila, who deserts him for his brother, leave little doubt as to why Reggie Joyce has come to the Far East. Bored and frustrated, the only excitement in his old life came from risking his neck as a professional motorcycle racer. (That was also Jack Reynolds’ former profession, and his father was a man of the cloth too.)

Anyone who has ever lived or travelled widely outside their homelands is bound to identify with Joyce’s wanderlust.

Poster for the 1960 film version which comes off as a romantic comedy now.

BANGKOK BARGIRLS

In the dance halls of Bangkok’s Ratchadamnoen Road (the last of them demolished in the early 1990s), he meets the beautiful Vilai, better known as the “White Leopard” for the way she stalks her carnal prey and extracts money from them. She fancies herself the queen of the Bangkok bargirls.

The difference between the two anti-heroines’ perceptions of themselves is revealing. While Vilai proudly refers to herself as the “number one bad girl in Bangkok,” Suzie Wong frequently chides herself for being a “dirty little yum-yum girl.” In that light, Suzie is the more likeable and repentant character. She is not literature’s original “hooker with a heart of gold” (that would probably be the devoutly religious Sonia in Dostoievsky’s Crime and Punishment), but her intentions are good and she is a doting mother.

In the book’s most poetic and preposterous scene, after they fall in love the narrator casts Suzie in a saintly light with an angelic hue. The section is rife with the kind of Christian sentiment – the fallen woman resurrected by an honest man – which bears little relevance to Buddhist and Confucian cultures. It also comes off as condescending, because Suzie is a scrappy little survivor. Raped by her uncle in Shanghai while still a teenager, she knew that she could never be a virgin bride for a rich husband. So she came to Hong Kong’s seedy Wanchai district, which can still be pretty seedy in the wrong places and on the wrong side of sobriety, to cash in on her looks. It’s a pragmatic plot riff that still rings true all over Asia.

Reynolds avoids any blow-by-blow descriptions of the White Leopard’s work night; he yearns to penetrate her life in deeper places. The book’s pinnacle is the mid-section, which is entirely written from her point of view, as she sees to her ablutions, scolds her servants, sits down to lunch on the floor, paints herself for work with an artist’s dedication to his palette, and rejoices in her beauty and the men she swindles. All the while the author masterfully evokes the sounds and smells of the Thai capital circa 1955 in sensual prose reminiscent of DH Lawrence (Lady Chatterley’s Lover). Such a comparison also does the author a disservice, however, because Lawrence never wrote about any women who were so far out of his own cultural milieu.

The 2012 version of the tome published by Monsoon Books.

For books that trade on their risqué nature, whether it’s Miller, Jong, or Jack Kerouac, it’s a familiar story: what came off as shocking then looks quaint now. But these two novels have aged well because of a divide between how sex is portrayed in the media as the byproduct of a glamorous and healthy lifestyle (a la the ads for designer lingerie, chicklit novels, rom-coms, and shows like Sex in the City), which is the Western perspective, as compared to how these books treat sex as a product in and of itself, which is still the bottom line in much of Asia.

When it comes to the ins and outs of the oldest profession not much has changed. What has changed are the reference points. By the mid-1950’s Freud’s theories had been regurgitated by so many different intellectuals, authors and physicians that they’d become baby food for the masses. Mason chewed them over again and here’s what he spat out. The novel’s most annoyingly stereotypical character, a wealthy American expat, has been instructed to take a lengthy holiday by his psychiatrist, so he can meet new women and escape the clutches of his – yes, you guessed it – overbearing mother. The stodgy Brit, meanwhile, whose mind and libido have been freed by regular dalliances with Suzie has come up with the earth-shattering epiphany that all the world’s woes stem from carnal desires that have been stymied. (Tell that to any slum-dweller anywhere in the world and see how many neo-Freudian converts you can make.)

At the end of Chapter 1, the narrator does pay homage to her perceptiveness, though: “Suzie may not have read Freud, but as a psychological observer she was pretty shrewd.”

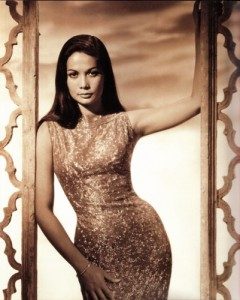

Nancy Kwan is brilliant as the scrappy heroine in the movie version of Suzie Wong, which is also a great travelogue of Hong Kong from a bygone era.

Both authors show due deference to the different cultures they encounter, Reynolds describing Thai classical dance with great panache, Mason detailing Suzie and the narrator’s visit to her fortune-teller without any smirking asides. When one of the other expats moans about how slow and dull Thai dance is – those complaints haven’t changed either, though you will hear them from plenty of Thais too – Reggie Joyce thinks, “And this from a member of the race which invented the jitterbug.”

The main difference between these two first-person narrators is honesty. Are we really to believe that a young, single man can live and paint in a Hong Kong hotel and brothel for months on end without ever succumbing to a single bout of lust? Unbelievably, the artist pines and waits only for Suzie.

Reggie Joyce is more convincing. His apprehension about losing his virginity in a provincial Thai brothel is rendered so palpably it could give readers a skin rash and a nervous tic.

Yet a similar fault line runs through both books. Halfway through them the subplots and minor characters disappear. The suspense goes flaccid. Only two questions remain to be answered: Will the narrators settle down with their respective women and enjoy a sappy ending? Or will these torrid affairs be doused in cold recriminations and end miserably?

Actually, in Joyce’s case, and the many other foreign memoirists who get fleeced repeatedly by floozies in Thailand, there is one other query: How could anyone be so stupid and gullible?

Since good literary novels authored by expatriates in Asia are such a rare commodity, partly because they are so commercially unviable, the reappearance of A Woman of Bangkok and The World of Suzie Wong is a bonanza for readers and historians. No question that Jack Reynolds (who was still writing for The Bangkok Post until his death in 1984) was the superior author, but the novel by Richard Mason (who died in Rome in 1997) remains the more relevant read, Freudian and Christian trappings aside. After all, at the Suzie Wong Go Go Bar on Soi Cowboy, the same kind of racy vignettes that he penned more than 60 years ago are still being reenacted on a nightly basis with Bangkok bargirls.

The 2018 edition of Jim Algie’s latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of Rock and Punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway” features zero bargirls or red-light scenes, because the music world is far too debauched for such tame entertainment. It also contains a new 130-page, nonfiction section of “Rock Writings and Musical Memoirs,” and a cover blurb from the acclaimed author Timothy Hallinan, “The funniest sad book and the saddest funny book I’ve read in a long time.” The book is available as a paperback or ebook from Amazon.com.

Recent Comments