Before his name became synonymous with Thai silk, the most famous expat in Thai history was a soldier decorated for bravery. In this excerpt from the new book Americans in Thailand, I try to disentangle all the colorfully embroidered yarns and misunderstandings about silk trader Jim Thompson, a silver-tongued salesman with a marvelous eye for color and covert connections with independence groups warring with authorities for autonomy all across Southeast Asia.

James Harrison Wilson Thompson was named after his maternal grandfather, General Wilson, who rose through the ranks to become a major general at the age of 27 and a friend of General Ulysses Grant. Once the clamor and cannons of the Civil War died down, General Wilson travelled through China for a year to see about putting his engineering skills to the test by building a railway – a journey he chronicled in a book called Travels in the Middle Kingdom which would have served as his grandson’s introduction to Asia. The young boy was also mesmerized by the photos he saw of the Siamese royal later crowned as King Rama VI visiting his family home. (General Wilson had befriended Crown Prince Vajiravudh while attending the coronation of King Edward VII as a military representative of the U.S., while Thompson’s sister and life-long friend, Elinor, also became close to the prince.) In spite of these influences, his biographers have noted that there were few hints in Thompson’s early life which suggested a career in the military or that he would one day become famous as the titan of Thai textiles, although his first career as an architect, smitten with painting and enchanted by the ballets he saw in New York (especially the sets and costumes) gave him both an eye for color and an appreciation for the exotic and extravagant.

At an age when most men are settling into their careers and settling down with wives and children, Thompson, then in his late thirties, grew disillusioned with his work and spinning his wheels in the same social circles, writes one of his most prominent biographers, William Warren, in Jim Thompson: The Unsolved Mystery (reprinted by EDM Books in 2014). Warren reckons that it was his belief that America would soon be involved in the war, and that he needed to do something about it, that helped to catalyze this change. Now a Democrat not a Republican as he had been before, Thompson enlisted as a private in the Delaware National Guard Regiment. The trajectory of his career in the military flew neither high or fast. But a friendship with Second Lieutenant Edwin F. Black, who encouraged him to join the OSS, was the turning point. In Washington he trained at the same camp as The Bangkok Post founder. By Alexander MacDonald’s account, the drills were brutal. “We were taught to lie and steal, kill, maim, spy, deceive, terrify and destroy. It was the Ten Commandments in reverse. There, for example, the class in personal combat, was led by a former police colonel from Shanghai. He taught a gutter type of karate. He demonstrated how to chop with the hand at an adversary’s windpipe, how to grip an arm so that the finger bones could be crushed, how to immobilize a rival by pressing a certain nerve in the neck. ‘And don’t ever hesitate,’ he urged, ‘to go after the balls.’”

At an age when most men are settling into their careers and settling down with wives and children, Thompson, then in his late thirties, grew disillusioned with his work and spinning his wheels in the same social circles, writes one of his most prominent biographers, William Warren, in Jim Thompson: The Unsolved Mystery (reprinted by EDM Books in 2014). Warren reckons that it was his belief that America would soon be involved in the war, and that he needed to do something about it, that helped to catalyze this change. Now a Democrat not a Republican as he had been before, Thompson enlisted as a private in the Delaware National Guard Regiment. The trajectory of his career in the military flew neither high or fast. But a friendship with Second Lieutenant Edwin F. Black, who encouraged him to join the OSS, was the turning point. In Washington he trained at the same camp as The Bangkok Post founder. By Alexander MacDonald’s account, the drills were brutal. “We were taught to lie and steal, kill, maim, spy, deceive, terrify and destroy. It was the Ten Commandments in reverse. There, for example, the class in personal combat, was led by a former police colonel from Shanghai. He taught a gutter type of karate. He demonstrated how to chop with the hand at an adversary’s windpipe, how to grip an arm so that the finger bones could be crushed, how to immobilize a rival by pressing a certain nerve in the neck. ‘And don’t ever hesitate,’ he urged, ‘to go after the balls.’”

DECORATED SOLDIER

During World War II, Thompson was decorated for bravery while serving with the OSS in Europe. Transferred to Asia, he and MacDonald were about to parachute into northern Thailand to help the Free Thai movement when they heard over the radio that Japan had surrendered in August 1945.

Like MacDonald, the future silk trader Jim Thompson also elected to leave the service and stay in Bangkok. That was where he first kindled his passion for Thai arts, crafts and curios, buying a selection of them to take home to his wife, only to find she had left him for a friend of his. Those betrayals only strengthened his resolve to return to Bangkok. First he tried to renovate and relaunch the Oriental Hotel, then a dilapidated mess where he lived. After that joint venture with the Frenchwoman Germaine Krull ended in failure and they parted on acrimonious terms, Thompson, divorced and disheartened, looked for another line of work. In any chronicle of his rise from that of an ardent admirer of Thai silk to a global magnate, the figure of James Scott, a commercial attaché at the American embassy in Bangkok, loomed large. It was Scott who told him about his experiences working in Syria where silk brocade underwent a radical transformation from cottage-industry curiosity to a full-fledged commodity in the export market. As Warren mentions, Scott was also a fan of Thompson’s growing collection of local silks and thought that the success he’d seen in Syria boded well for a Thai spinoff.

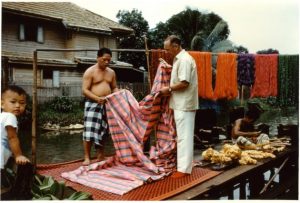

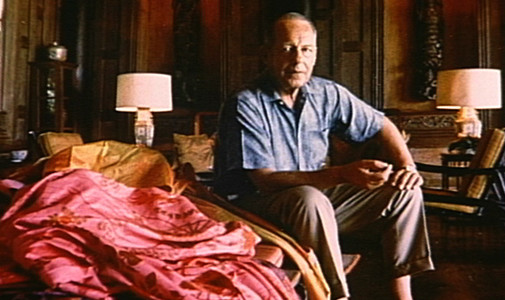

Jim Thompson had an extraordinary eye for striking color combinations.

No matter how much help and advice he received, Thompson’s industriousness cannot be overlooked or his skill as a silver-tongued salesman. At the time, the silk trade was hanging by a thread in Thailand, both literally and metaphorically. Even in the traditional cradle of this art, the northeastern region of Isaan, the country’s largest, poorest and most infertile area, production had tapered off. Many saw silk as an unfashionable relic with no hope for a rebirth. Thompson thought otherwise. As an aspiring businessman with a deep affection for local artisans, he explored the northeast with his Laotian friends, absorbing all he could about the mulberry tree whose leaves nurture the silkworm, the vegetable dyes used to give the fabric color, along with the warp and weft of local customs related to silk. What he witnessed was a dying craft at risk of extinction thanks to machine-made textiles and the fickleness of fashion. (Premier Pibul’s attempt to modernize Thailand in the late 1930s included issuing edicts that urged Thais to wear Western-style hats, shoes, shirts, and give up other traditional habits like chewing betel nuts.)

The background of Jim Thompson in intelligence paid off in other ways, as he tracked down traditional weavers in the Muslim community of Bankrua in Bangkok. He then took some of these swatches to New York where a friend put him in touch with the influential editor, Edna Chase Woolman, of the fashion trendsetter Vogue. As Warren notes, “According to his account, she took one look at the pile of glowing material, stepped back, and announced to her secretary that none of the staff was to leave the offices that day without seeing this magnificent new discovery.” Her encouragement was crucial to the founding of the Thai Silk Company in 1948, as was the buying of shares by George Barrie, a maverick entrepreneur from California. Capitalized at 25,000 dollars, the company’s start-up fund came from 500 shares which sold for 50 dollars each. But Thompson was never in it for the money. By the year of his disappearance in 1967, when he was a figure of world renown credited for reviving and popularizing the textile, he was still only paid 33,000 dollars a year. He still worked six days a week and, for the most part, he shunned air-conditioning and other modern conveniences. At his sprawling Thai-style home in Bangkok, later transformed into a first-class museum that remains one of the country’s biggest tourist attractions, he even refused to put screens on the windows. Much of his money was spent on his house and his collections of artworks, fabrics and antiques. Otherwise he did not live large. What Thompson aimed to do, writes Warren, a friend of his fond of attending the lavish dinner parties he gave for famous guests like Robert Kennedy and Truman Capote, was to make a positive contribution to the lives of these poor yet talented artists, and ensure that they received their fair share of the profits. In doing so, he kept many of these traditional practices from unraveling and preserved the fabric of many rural communities, steadfastly refusing to modernize the business by relegating the weavers to factories and denigrating their art through the use of assembly-line processes.

Silk trader Jim Thompson did daily inspections of the yarn for quality control.

STRANGE DISAPPEARANCE

STRANGE DISAPPEARANCE

The disappearance of Jim Thompson in the Cameron Highlands of Malaysia in 1967 has been the springboard for much conjecture with little (if any) hard evidence to back it up. One theory is that he went for a hike in the hills and got eaten by a tiger or fell into an animal trap, his death hushed up by an embarrassed Malaysian government or an aboriginal tribe. Another rumor is that, tiring of fame and life, Jim Thompson staged his own disappearance to live out his final years in peaceful anonymity (many tabloids have said the same of Elvis Presley and Jim Morrison.) One of the more hotly contested debates is whether his disappearance was related to his days of espionage in the OSS, and rumors that he continued spying for the American embassy in Thailand. Warren discounts the latter claim in his biography. It is likely, he notes, that Thompson did some spy work up until the coup of 1949, when he discovered that three of his close friends – pro-Pridi politicians – were slain by the police. Another Laotian, Tao Oum, who had been his right-hand man and was also a resistance fighter, feared for his life and opted to return to his homeland instead. During another research trip to the northeast at this time, Thompson lost yet another friend who was abducted by the police and later executed. The American’s letters home after these losses revealed his personal grief and political cynicism. After that he rarely moved in those circles again, claimed Warren. Nor did he show much interest in debating such matters. Considering his busy schedule of working and socializing, when he was rarely alone, how could he find the time for espionage?

To the contrary, others believe that Thompson’s repulsion for the American-backed strongmen like Phibul and Phao, and his belief in supporting nationalist forces, inspired him to work against – or at least apart from – his former cronies. Given his former position in the OSS and his knowledge of the region, Thompson’s contact network of rebel fighters and underground movements was extensive. Kurlantzick details them in The Ideal Man: The Tragedy of Jim Thompson and the American Way of War, published in 2011. He summarizes a U.S. government investigation from 1950 into Thompson and other one-time agents from the OSS suspected of smuggling arms, which concludes that he had “close and mutually beneficial relationships with the Viet Minh, Khmer Issara, and Lao Isarra.” The report also stated that Thompson “abetted the release and concealment of parachute-delivered American weapons (a stockpile for his future trafficking) instead of gathering them for Allied forces’ use [at the end of World War II], or to hand over to the Thai government.” In spite of these accusations, Washington did not cut him loose, mostly because he was too valuable as a source of intelligence, Kurlantzick surmises. But the 2011 biography also explains that by the middle of the 1950s the CIA had issued a stern directive that Thompson was no longer to be trusted or consulted. U.S. ambassadors in Bangkok and Laos had also taken him aside to say that his meetings with Vietnamese nationalists had to stop. Once again, whether Thompson was a brilliant spy adept at covering his tracks, or simply not guilty of colluding with the enemy, when the FBI launched an extensive investigation into Jim Thompson in 1953, going over his government files with intense scrutiny, conducting undercover interviews with his old friends in the U.S. and business associates in Bangkok, they concluded that he was not guilty of, in the parlance of the day, “un-American activities.”

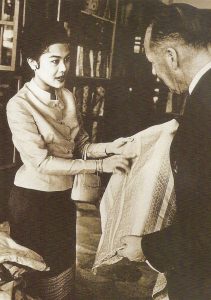

Queen Sirikit inspects some cloth with the titan of Thai textiles

During that momentous trip to Malaysia in 1967, and on the last day he was seen alive, Thompson seemed on edge and, uncharacteristically, in bad humor, his travelling companion and old friend, Connie Mangskau said. Her reminiscences bred hearsay that he was the victim of foul play. Whether it was business rivals, the disgruntled husband of a married woman he had been involved with, the settling of a political debt or a kidnapping gone wrong, these whispers remain mere rumors. The fact that this heavy smoker left his cigarettes and lighter behind, as well as the medicine he used to remedy his agonizing gallstone attacks, suggested that he did not leave the premises of the Moonlight Cottage willingly.

Had he been attacked and killed by a tiger or leopard would there not have been traces of blood or scraps of clothing left behind? Whatever the cause or nature of his disappearance, and in spite of all the searchers and psychics, the conspiracy theorists and crackpots, the biographers and journalists who have compared him to such fictional characters as Jay Gatsby and Alden Pyle (the naïve yet well-intentioned OSS agent in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American) the disappearance of Jim Thompson is still a mystery. Less enigmatic by far is that the company he founded is a worldwide enterprise, thanks in no small part to his second in command, Charles Sheffield, who took the reins after his disappearance, and that the name Jim Thompson will forever be synonymous with Thai silk. In fact, and as a matter of fiction, the American’s legend has taken on the epic proportions of myth, continuing to fascinate and confound as it inspires even more embellishments and revisions. In 2013, T Hunt Locke, an American author based in northern Thailand, published a thriller called Jim Thompson Is Alive!

Americans in Thailand, written by Jim Algie, Denis Gray, Nicholas Grossman, Robert Horn, Jeff Hodson and Wesley Hsu is on sale in Southeast Asia for 1,290 baht and also through Amazon.com.

This excerpt from the book was written by Jim Algie

Recent Comments