As a photographer Martyn Goodacre is mostly remembered for his famous black and white shot of Kurt Cobain, but he framed many more stars of rock, cinema and literature before living in Thailand for many years.

The music business is a Roman circus of debauchery and cruelty where so many performers are dispatched by the needle or the bottle, or left to rot by the wayside when the hits stop, the critics pounce and the crowds turn on them. As the thunderclaps of applause turn into a chorus of jeers the rock heroes of the last decade are demoted to this year’s reality show has-beens, while the majority of musicians grind it out year after year in poverty and obscurity, playing small clubs and touring in vans if they’re lucky, recording jingles for ads or teaching music if they’re not, waiting for a break that will become a broken dream.

Few people have seen both sides of this insanely bipolar business – the grandeur and the squalor – like Martyn Goodacre, who didn’t get in on the ground floor of rock photography so much as crawl his way up from the bottom of basement clubs and squats (sometimes quite literally) in the late 1980s.

At that time, he was taking photos of bands playing at the University of London Union and publishing them in the university newspaper. “I was around 27 then and thought I should finally find a career after eight years of squatting in London. So I got a portfolio together to show the music paper SOUNDS. They told me to shoot more gigs and come back and see them. So I went to a gig every day for a week, printed them all up, and the editor didn’t remember me, and then said he meant come back in three months and told me to piss off,” said Martyn, who hails from the central English town of Malvern (pop. 30,000).

“Then I went to see Melody Maker with some photos of the Screaming Trees I’d just taken and they were doing a story on them, so they bought a photo then and there, and two months later I had three photos in one issue of the NME, of Happy Mondays, the comedian Emo Philips, and The Family Cat. Then I didn’t get any work for two months,” he said.

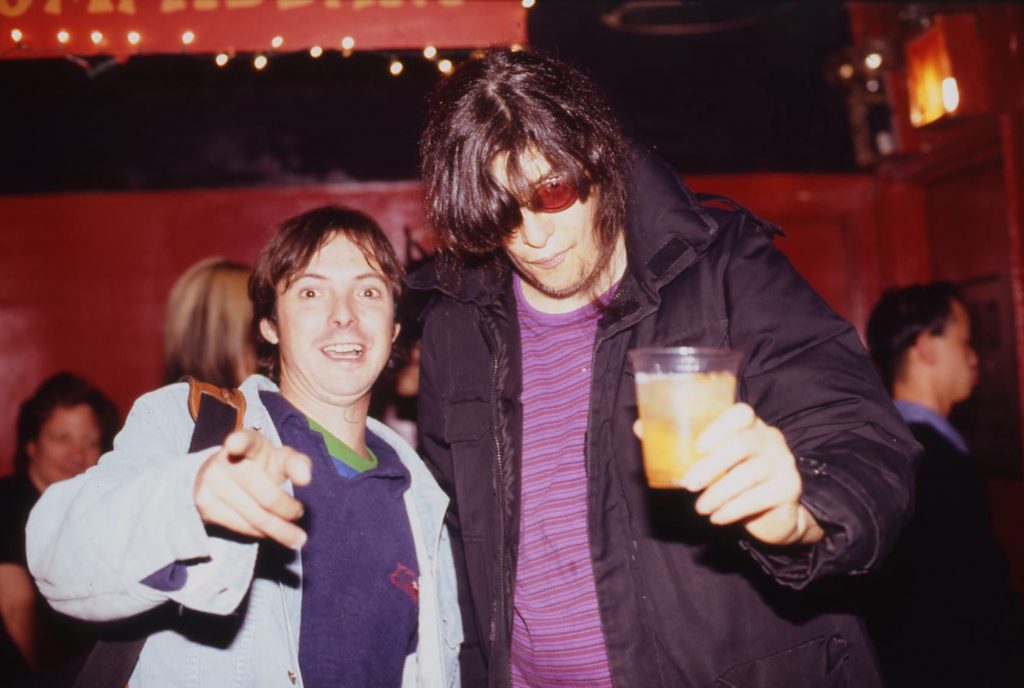

Back then, the bigger music mags in the UK were paying 23 pounds per photo and double that for a colour image. But the perks for the higher-profile shooters were on a par with the celebrities they shot: getting flown to New York, Los Angeles and Paris on a regular basis to be put up in five-star hotels, with all the free booze, parties and food they could stomach. He got to drive around with the late INXS frontman Michael Hutchence in his Ferrari, watch a drunken Shane MacGowan do gangster impersonations in front of actor Harvey Keitel, and go carousing in New York with Joey Ramone. “I’ve been disappointed by meeting so many of my heroes, like Jonathan Richman, but not Joey Ramone. He was a very humble guy,” said the photographer.

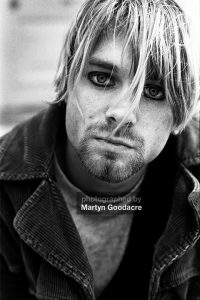

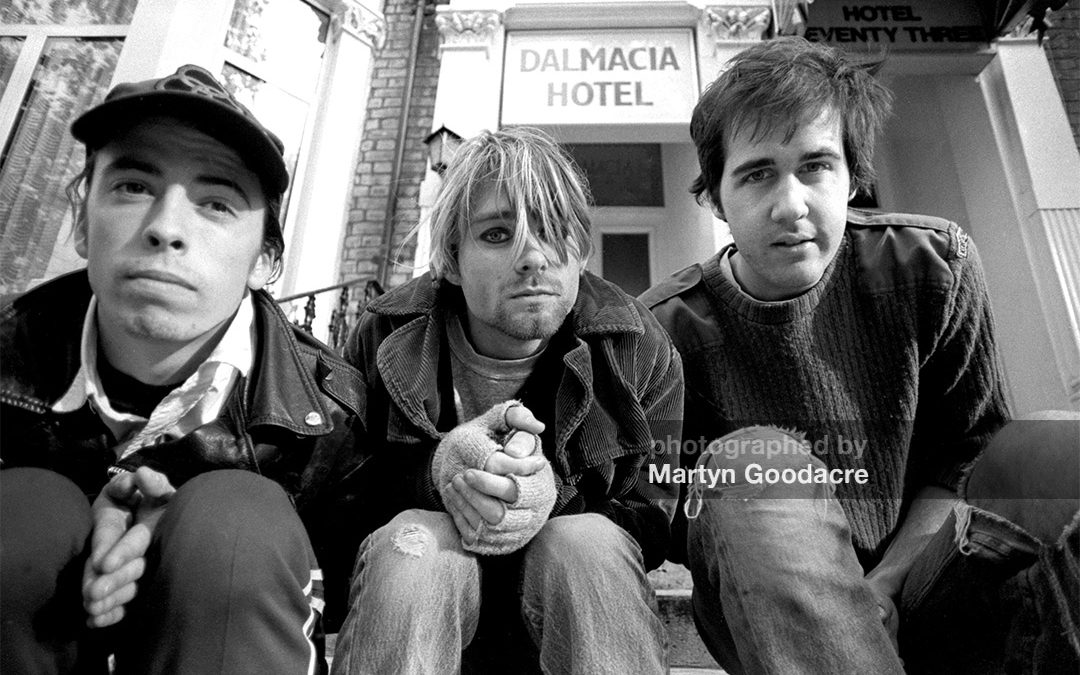

Kurt Cobain in 1990.

Martyn’s most famous image, a black and white shot of Kurt Cobain, has been hijacked for T-shirts, posters, websites and festooned on the cover of the NME. If its history of piracy is murky the time frame is clearly London in 1990. “They weren’t famous yet, but their first album had come out and more recently, the single ‘Sliver’ so they were touring with Tad and staying in a basement bed and breakfast. Kurt Cobain was a tiny little guy who seemed quite miserable and hardly spoke two words. Actually, I remember taking this photo quite clearly because in all the others, his eyes were a bit squinty, but then he opened them up completely.”

As an acerbic aside, he added about the pic of Kurt Cobain, “I haven’t made a tenth of the money I should’ve from this photo. They’ve used it for posters and T-shirts all over the world.”

Of all the stars now deceased that he once photographed it was Michael Hutchence whose death he mourned the most. “He was a pure gentleman. I was more upset about him dying than anyone else [I’ve ever photographed]. It was just about a year before his death, and you could tell he was under a lot of pressure. It was near Christmas time, and Paula and the kids couldn’t come over and meet him because of Bob Geldof. Altogether we spent three days with Michael, and everywhere he went in Sydney people would say hello and show him so much respect.”

Michael Hutchence only a year before his premature demise in 1997 that is still a matter of speculation, gossip and morbid innuendos.

How and when did the gravy train derail for rock photographers? “It slowed down in the second half of the 1990s. Record companies made a mint out of CD releases and the high costs they were charging. So they had shed-loads of cash to blow. They were so coked up and complacent that they missed the chance to get a grip on the downloading business. Hence a computer manufacturer took over… Apple,” said Martyn.

During his glory days as a rock photographer, Martyn also played rhythm guitar with Fabulous, a British pop-punk band which released three singles in the 90s. The group’s manager, James Brown, who had been the features editor at the NME, turned the band’s shagging, snorting and strumming lifestyle into a template for a magazine called Loaded that revolutionised the publishing industry and spawned a legion of asinine impersonators. Martyn became one of the mag’s original photographers. “Before Loaded all the men’s magazines like GQ told you what kind of suit to buy, how to tone your biceps, and do stuff you couldn’t afford to do. Loaded said, ‘We’re men, but we’ve lost the plot, women have gotten the upper hand, and we’re just gonna have fun.’ Though people came to think of it as a tits magazine, James brought in some of the best writers around, people like Howard Marks. I have great memories of James dancing drunkenly on the table in the office and telling everyone they had to buy another bottle of champagne or they’d be sacked,” said Martyn, who now lives in Berlin and plays in a pop group called the Bed Monsters.

For an early issue of Loaded, he was sent to Koh Phangan to shoot the Full Moon Party, and ended up coming back to Koh Samui regularly, where he met a Japanese woman running a bar on Bohput Beach, where he lived for many years. The couple has a daughter.

Kim Deal, during her days as the bassist of the Pixies, circa 1995.

So why did he quit shooting stars?

“I just got a bit bored of it really. It’s good fun seeing yourself in print, but you’re doing the same thing again and again. I didn’t like the new bands so much, I got sick of going to gigs, and you just get too old for that.”

Since he started out, the media landscape has been so radically uprooted and altered by the digital world, do any rock photographers still make a decent living?

“I think it’s tough but most of the big ones are still hacking away. I get so many requests for my images to be used for free as nobody wants to pay for content anymore,” said Martyn.

Finally, a question that must be asked, and knowing the high notes and low blows this man has seen and suffered, we may well expect a bitter or nostalgically hedonistic response, but is there anything he misses about the music business?

“I miss all the free records.”

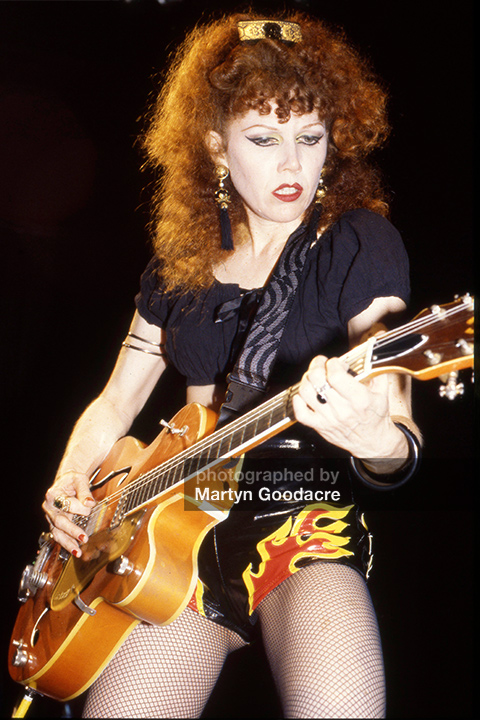

Poison Ivy of the Cramps, who disbanded in 2009 after the death of frontman Lux Interior. In their early years in New York, Ivy supported the band by working as a dominatrix. Later she adopted that look and personae onstage.

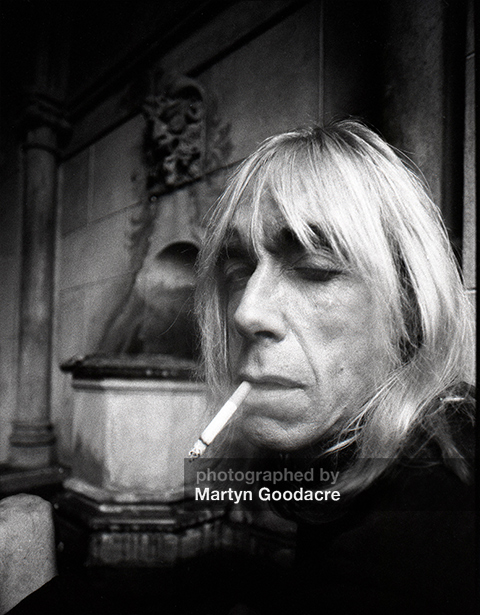

Punk progenitor Iggy Pop’s exhaustion lifted when Martyn mentioned his former bassist, Craig Pike of Thee Hypnotics, had died of a heroin overdose.

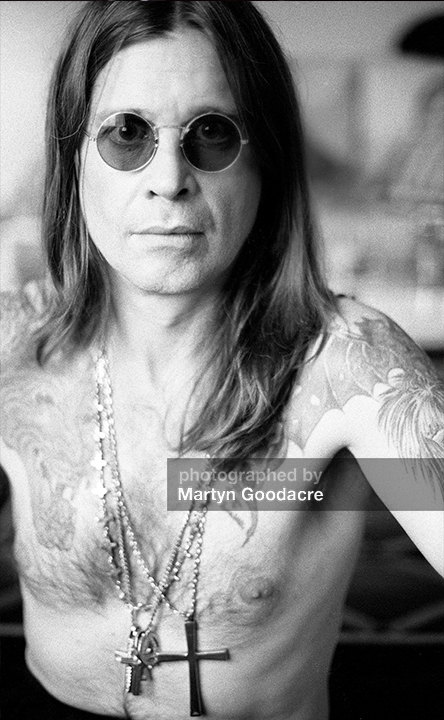

Ozzy Osbourne, a man who needs no photo caption, in 1998

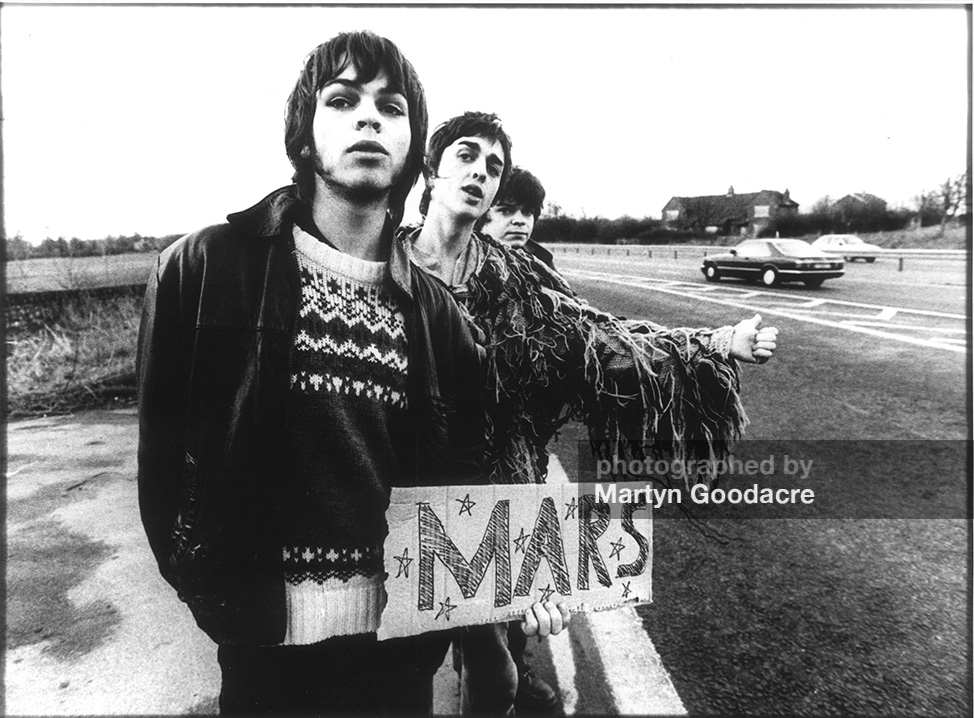

Supergrass on the road to superstardom.

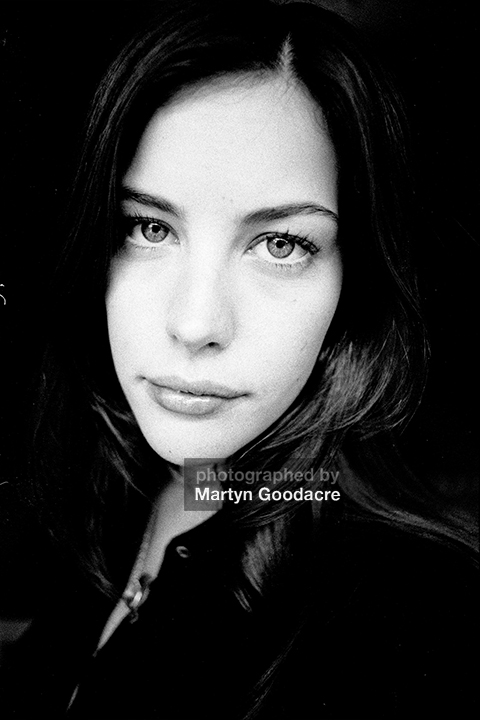

Actress Liv Tyler, daughter of the Aerosmith singer, on a promotional tour for the 1996 film Stealing Beauty, directed by Academy award-winner Bernardo Bertolucci.

Martyn followed Spinal Tap around for a whole day as they did interviews at different radio stations to promote their reunion tour and DVD of 1992. “They stayed in character the whole time. It was like living in a Tap movie.”

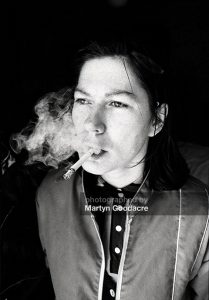

The late Howard Marks, aka “Mr Nice,” with his trademark spliff, on Jamaica, where the two of them worked on a travel story for Loaded that was never published.

“In New York in 1998 I was there to shoot Skunk Anansie, and I was with this writer in a club in the East Village called Coney Island Baby, and the writer spotted Joey Ramone. I wouldn’t have recognised him, because he was wearing a purple anorak with his grey hair and a pony tail tied up. He was producing a London all-girl punk band called Fluffy, and all the girls were slagging me off because I worked for the NME, but Joey defended me and told them to back off, maybe because I was telling him how much The Ramones had inspired me. I wish I could remember more about what we talked about after all those Long Island Ice Teas, but for the next two hours we mostly just reminisced about punk rock. I’ve been disappointed by meeting so many of my heroes, like Jonathan Richman, but not Joey Ramone. He was a very humble guy.”

For more cool pics, check www.martyngoodacre.com.

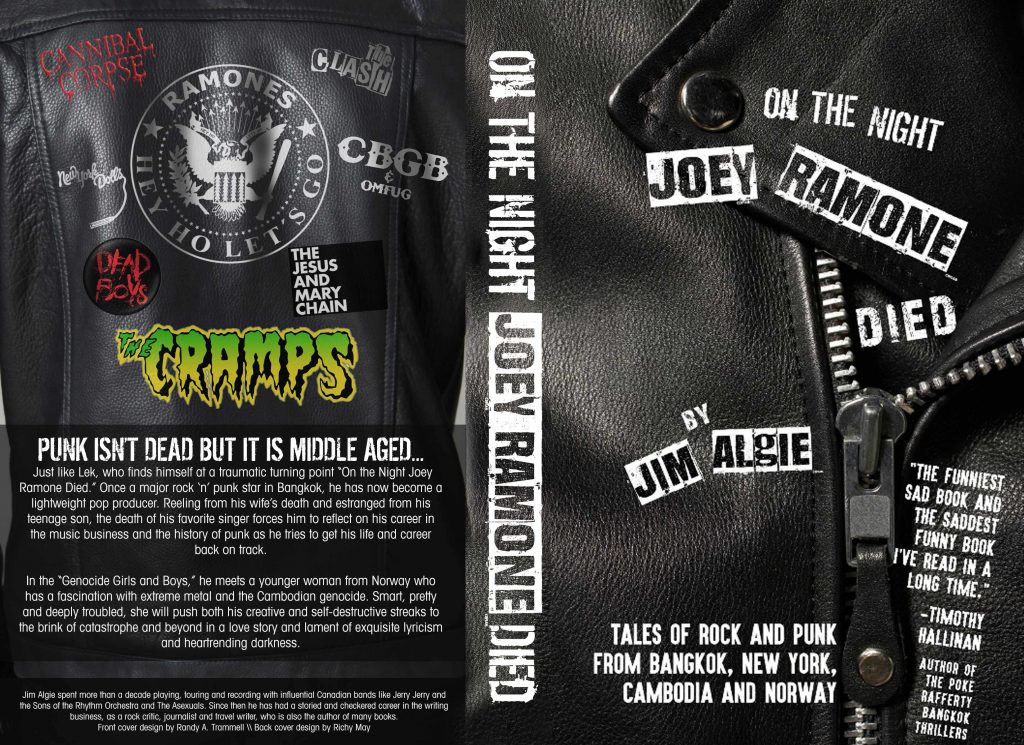

Jim Algie has written about punk history, his own experiences as a musician, and the lives of rock stars in the book On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of rock and punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway, available from Amazon as an ebook for US$3.99 and a paperback from Amazon for US$12.99.

The revised cover of the first paperback edition, released in February 2018, includes a new front cover blurb from the renowned author, former singer and hit songwriter, Timothy Hallinan: “The funniest sad book and the saddest funny book I’ve read in a long time.” In his Amazon review, Tim added, “The book also captures the pop music world as well as, and in some cases better than, most rock autobiographies.”

Great photos the pic of Kurt Cobain has a real haunting quality about it. I remember reading NME a lifetime ago ,the writing could be often filed away as pretentious but the photography compensated. Alas on my one (so far anyway) trip to Koh Samui I failed to meet and fall in love Japanese woman or any woman who kept a bar. hope springs eternal.