Before I was born my mom used to go and see Leonard Cohen do poetry readings in Montreal in the late 1950s. So I grew up with his novels and poetry collections on our bookshelves.

She did not listen to his music though, so that epiphany had to wait until 1985 when I’d already been playing in punk and new wave bands for five years and was looking for some new musical muses and different strains of music to riff on. In between music videos by Culture Club, Duran Duran, Toto and Madonna playing on Much Music (Canada’s MTV) appeared a pallid man in a dark suit intoning, as opposed to singing, in a voice as mournful as a foghorn, “Dance me to your beauty with a burning violin/Dance me through the panic till I’m gathered safely in/Lift me like an olive branch and be my homeward dove/Dance me to the end of love,” over a melody that I could not place on any musical map of North America or Britain.

The somber yet dapper figure he cut and the lyrical lines he wove transfixed me. Nobody was singing lyrics like these on AM or FM radio, or MTV, or on the alternative stations of campus radio. Nobody sang or dressed like him either.

The next day I went out and bought his new album Various Positions and his Greatest Hits record from 1975.

Many bios of Leonard Cohen’s life have been sketched, as well as notations of his discography, since his passing in November 2016. For full-length biographies, Sylvie Simmons’ 2012 I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen is the best I’ve read.

I am not out to reiterate any of these other odes or obituaries. I only want to bring up a few points that have been not been mentioned or given short shrift. Though I’ve had to play the omnipotent critic role many times before, this is strictly personal.

HIS WILDERNESS YEARS

To be a Leonard Cohen admirer in the early to mid-1980s was to be part of a small yet devoted sect that included a few other underground rock musicians and Bohemian babes I knew, along with some bigger musical names from that era, like Nick Cave, Echo and the Bunnymen, and the Jesus and Mary Chain, for these were his wilderness years when he was presumed to be irrelevant and washed up. For many his name had become a punch line to joke I didn’t find funny. At a house party, I remember some drunken punk chick yelling in the kitchen at 3am, “Why is everyone ignoring me? What am I? A Leonard Cohen record?”

But on the first album by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, From Her to Eternity, the band’s cover of Cohen’s “Avalanche” came as a pivotal moment in 1980s’ rock as the so-called “King of Goth” took on the mantle of the so-called “Godfather of Gloom.” Cohen appreciated that version, saying he admired Cave’s “instincts for tearing that song apart.”

But on the first album by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, From Her to Eternity, the band’s cover of Cohen’s “Avalanche” came as a pivotal moment in 1980s’ rock as the so-called “King of Goth” took on the mantle of the so-called “Godfather of Gloom.” Cohen appreciated that version, saying he admired Cave’s “instincts for tearing that song apart.”

The original version of the tune was too dark for the “Summer of Love,” too literate for the disco era, not angry or sloganeering enough for punk. Only in the 1980s, that new dark age of Reagan and Thatcher, of “trickle down economics” and massive corporate tax cuts, of poll tax riots in England and the first war against drugs in the US, did the apocalyptic vision of Leonard Cohen prove, if not prophetic, then at least much more realistic than his detractors had claimed.

In that time of blighted hopes and diminished expectations, and in that climate of murk and despair, the opening line of “Avalanche,” “I stepped into an avalanche, it covered up my soul,” looked like a weathervane pointing to the thunderheads massing on the horizon. Next to Cohen, the lyrics of most of the Goths and industrial bands made them seem like lightweights.

The dominant genres in the rock underground then were hardcore and all the new strains of metal (black metal, speed metal, thrash metal, most of which sounded like “shit metal” to my ears). These were juvenile genres composed of screaming instead of singing and moshing instead of dancing. The gigs were more like sporting events and demolition derbies than concerts with teenaged boys, high on testosterone, running around and slamming into each other. Most of them were not there for the music, but to get drunk, to get laid, and failing that, to get in a fight or commit some wanton acts of vandalism.

The hardcore and metal songs may have had five or six chords in them, but the dominant note was always the same: anger. And the lyrics, when you could actually decipher them, were little more than clichés with nursery rhyme schemes, or simplistic political slogans, except for a few rarities like the Dead Kennedys and SNFU.

The songs of Leonard Cohen, with their elaborate word play, slow tempos, Spartan instrumentation and lack of volume, were a welcome counterpoint. The vocals and words displayed a degree of vulnerability that gave them the intimacy of confessions whispered in the dread of night, but were infused with enough poetry that they also had an air of mystery about them which encouraged and rewarded multiple plays.

Far from all the phony macho posturing and boasting of hardcore, metal, rap and their great grandparent, the blues, Cohen bemoaned his lack of handsomeness in “Chelsea Hotel #2,” his lack of bravery in “So Long Marianne,” his feelings of futility in “Take This Longing” (“all the useless things these hands have done”) and losing a woman to a “better man” in the same tune – even mocking his own singing in “Tower of Song,” revealing his panache for deadpan humor once again, “I was born with the gift of a golden voice.”

No singer or songwriter I’ve ever heard has sung with more honesty and wit about his own failings and shortcomings than Leonard Cohen.

I don’t find those qualities “depressing” (as many have called his music). Such confessions could also be taken constructively, for it takes a lot of courage to make yourself that vulnerable and, acknowledging your flaws, as we all know but often deny, is the first step towards fixing them.

Now I’m talking Pap Psychology 101 and a poet of his caliber is beyond such platitudes.

FINDING HIS MUSIC IN MONTREAL

FINDING HIS MUSIC IN MONTREAL

Only when I moved into the same neighborhood in Montreal where Leonard Cohen lived was I finally able to pinpoint where his music came from with more precision. Here were the Greek restaurants, the orthodox Jews and Jewish delicatessens, the Portuguese community, the finger-plucked riffs of flamenco guitar flitting from open windows, the Catholic cathedrals and the Blue Angel, a rustic country ‘n’ western bar, all of which stood in direct contrast to the city’s Parisian-style boutiques stocked with elegant fashions and the open-air cafes with their florid sundecks.

Some of my friends had spoken with Cohen in the neighborhood and all of them said he was a gentleman. But I never saw him in person or in concert until 1988, just after I’m Your Man came out. The album resurrected his career and reputation. Among us Cohenites it was a time of great jubilation. Not only was this one of his best records – he’d updated his sound with synths and drum machines – to my ears it was one of the best records of the entire 1980s, and launched one of the most unlikely comebacks in contemporary music.

Speaking of his renaissance, the maestro’s own reaction was somewhat glummer and wryer, telling the Montreal Gazette, I recall from memory, “Yes, I have been resurrected but I fully expect to be cast into oblivion again shortly.”

On the tour for that album, he played a hometown show at the Théâtre Saint-Denis, which remains one of the greatest concerts I’ve ever seen: a beautiful art deco venue with crystalline sound and a set list that balanced out the old hits with the newer material. Leonard Cohen was also a far better stand-up comedian and emcee than I’d ever anticipated. During the introduction to “Chelsea Hotel #2,” an old favorite of the faithful, he did a long monologue about how he met Janis Joplin in the elevator of the infamous New York hotel where Dylan Thomas, Bob Dylan and Dee Dee Ramone once lived and where Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols allegedly stabbed his girlfriend to death.

Of his encounter with Janis he said onstage, “Finally I gathered my courage and said to her, ‘Are you looking for someone?’ And she said, ‘Yes, I’m looking for Kris Kristofferson.’ I said, ‘Little lady, you’re in luck, I’m Kris Kristofferson.” The audience laughed. “Those were generous times. Even though she knew I’m somewhat shorter than Kris Kristofferson she never let on.”

MEETING THE MAESTRO

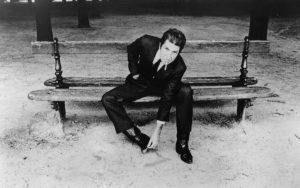

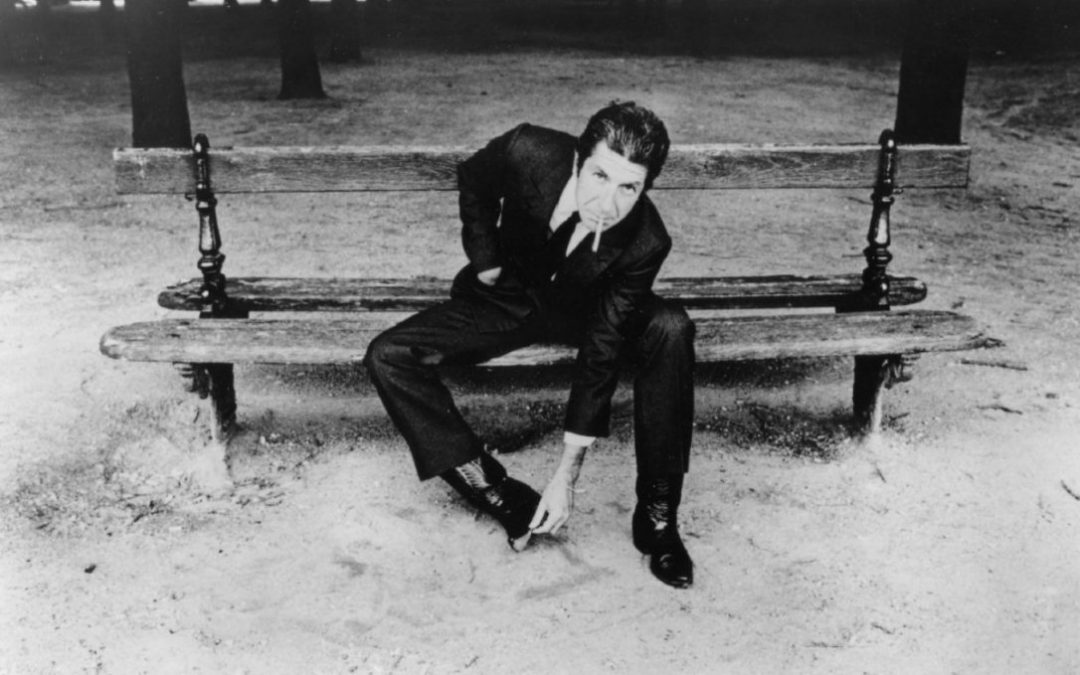

Only six months or so after that show I was sitting on a bench in the Parc du Portugal, near his house, enjoying a sunny day in the spring when the ice and snow were still melting and trickling down from rooftops to sluice across the streets. I looked over to my left and there was Leonard Cohen sitting a few benches down. He was wearing a suit and cowboy boots. Nobody but him could ever pull off that pairing.

I’d been reading his books and using his songs as aural Prozac for so many years now, and here he was in the flesh.

To have such an intimate (yet completely one-sided) relationship with a stranger is intimidating. At first I was star-struck then dumbstruck. What could I say to him that he hadn’t heard dozens of times before? Congrats on the comeback. Great show at the Saint-Denis. Thanks for all the music. Uhh, do you think you’ll ever write another novel? Have you heard Nick Cave’s version of “Avalanche”?

You do not want to look stupid or start stammering before a man of his eloquence.

So I had to rehearse an opening line in my head a few times before I walked towards the bench where he was sitting, with my chest wound tight as a snare drum.

This is kind of what Leonard Cohen looked like at the time I met him.

Standing before him and staring at his cowboy boots streaked with slush, I mumbled something like, “Hi, Leonard. Sorry to bother you. Just wanted to say thanks for that last show at the Saint-Denis, which was truly the most rapturous concert I’ve ever seen, and rapturous is not a word I would normally use to describe concerts, but I guess that’s the kind of spiritual and sensual energy your music has.”

When I dared to look up at him he was smiling shyly and holding out his hand. “Thanks so much, friend. Please sit down.”

I shook his hand and sat down at the opposite end of the bench, feeling something like a fervent Catholic meeting the pope.

I don’t know what I had expected exactly from him, but being invited to sit down and chat with him came as a shock to my central nervous system. At first, the conversation about the neighbourhood and Montreal in the springtime took a while to get rolling, as is often the case with strangers, until I mentioned that my mom had come to see his poetry readings when he was studying literature at McGill, and now I was studying the same subject at Concordia University.

After we found some common ground to stand on, the chat began in earnest. I knew he was an admirer of the Spanish poet Gabriel Garcia de Lorca, and had named his daughter Lorca. But was he familiar with Malcolm Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano about the Spanish Civil War and Mexico or ever heard that the ending referenced Lorca’s murder by Franco’s fascists? No, he had not heard that and was curious to hear more.

Much to my surprise, he asked me about my own writing and bands I was playing in, and what the music scene in Montreal was like then for us. That led into a lengthy digression about the rise of “cow-punk” and our mutual fondness for Hank Williams.

As the conversation warmed up, we sat a bit closer together and smoked some cigarettes. He had a very intense gaze, the kind you see with certain writers and photographers gifted with intense powers of observation, as if they’re taking everything in and filing it away for some future story or photo.

At one point I asked him if he’d ever considered singing rock and roll?

“I’d like to consider singing anything at all, but I have enough trouble singing my own songs. I appreciate the thought though.”

It was the first of many droll quips he made.

After an hour or so, he politely said he had to get ready for a dinner date. We stood up and shook hands. It was getting dark and the wind was lashing us with the cold whip of winter. Cars slushed by on the streets.

I said, “Thanks again for all the great music, books, and solace, that rapturous concert and for putting up with me for an hour. Now I get bragging rights that will certainly impress my band-mates and the cool Goth babes.”

He laughed and smiled shyly, “Pleasure to meet you, Jim. Thanks again for your many kind words and generous descriptions of my music and books. Best of luck with your own bands and writing.”

That was the last time I saw him.

Just as I’d finally discovered his music’s European pedigree in Montreal, after meeting him I came to conclude that the most Canadian qualities he possessed, either in his lyrics or in person, were a certain sense of warmth and graciousness, a certain humility and a great, self-deprecating sense of humor.

Leonard Cohen on the I’m Your Man tour with the backing vocalists, Julie Christensen (left) and Perla Batalla.

YOU WANT IT DARKER

Our favorite singers and their songs become woven into the neurons of our brains and the pixels of our memories. We look to them for solace, for spiritual counsel, for advice and wit. “For the workers in song” to borrow one of his phrases, and in literature, they also become the reference points and the gold standards one aspires to meet.

In my own stuff, there are so many Cohen references or riffs that they would be embarrassing to enumerate. To quote just a few brief examples from my latest book, On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Rock and punk tales from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway, two of the love songs the protagonist writes, “The Heir to the Throne of Her Heart” and “The Torture Chambers of the Hearts” both strain for the kind of poetic effect and dark romanticism that he achieved, seemingly so effortlessly, but if you anything about him and his work ethic, he labored over some of the those lyrics for years.

On the night of November 10, 2016, after his death had been announced, I held my own candlelight vigil, re-listening to many of my favourite tracks and watching some old performances and interviews on Youtube.

To my ears anyway, the title track of his final album, You Want It Darker, was his last masterpiece and one of the finest (and most original) songs he ever recorded. The echoes that song gave off reminded me of a TV interview I’d seen with him from maybe a decade ago where the interviewer asks him about the darkest times in his life, and Cohen says something like, “Even if I could remember I wouldn’t tell you, and compared to the people who are having bombs falling on them now, or having their fingernails ripped out in secret prisons, I don’t feel like I’ve had too many dark times.”

The sense of perspective in his work was, even near the end of his life, as acute as ever. Over a minor-key bass line that proceeds like a funeral procession, the maestro intones: “They’re lining up the prisoners and the guards are taking aim/I struggled with some demons they were middle class and tame/I didn’t know I had permission to murder and to maim/You want it darker, we kill the flame.”

Near the end of the song, when one of the singers from the Shaar Hashomayim choir, named after a synagogue in Montreal, begins wailing what sounds like a lamentation for the dead, always gives me a case of the winter chills.

One has to admire the man for refusing to tone down or lighten up his poetic vision of grim realism.

In watching some of the old interviews, I will miss the humanity and intelligence he brought to his art, his concerts and personal appearances. Here is a clip from MTV that came out around the same time as his album, The Future, which featured prominently on the soundtrack to Natural Born Killers. He refuses to indulge in any arrogance or show any bitterness about his lack of radio or video play. And the part where he discusses his up-tempo country song “Closing Time” from that album is a master class in lyric writing.

He also nails down one of the central problems of our time: the increasing importance of attitude and how that prevents us from reaching out to help each other. Since this 1993 interview that dilemma has only become even more distressing. What’s social media but a platform for attitude? What’s branding but a company’s attitude? What’s reality TV and all these talent shows but exercises in capitalizing on different people’s attitudes when put under stressful conditions full of judges and other contestants with differing attitudes?

As Cohen told MTV, “That’s why I’m against this contemporary investment in attitude, which is a refusal to pitch in. Helping someone out and pitching in is the obvious and urgent remedy to the kind of psychic predicament we are in right now.”

Who could argue with that humane wisdom?

It’s not within the scope of this miniscule and humble tribute to debate his legacy in music and poetry. I have the feeling that many younger musicians, fans and critics will be reading and listening to him for decades to come, and finding something different in those verses and tunes, just as we underground rockers of the 1980s reinterpreted his work to suit those bleak times and some of those bands recorded a dozen or so of those odes on I’m Your Fan.

In search of a fitting conclusion, when I was composing a recent elegy in words for my old friend, and a cornerstone of Thai indie rock, Wasit “Ooh” Mukdavijitr, upon the first anniversary of his death, I recalled that on his deathbed one of his constant companions was the Best of Leonard Cohen, his greatest hits package from 1975.

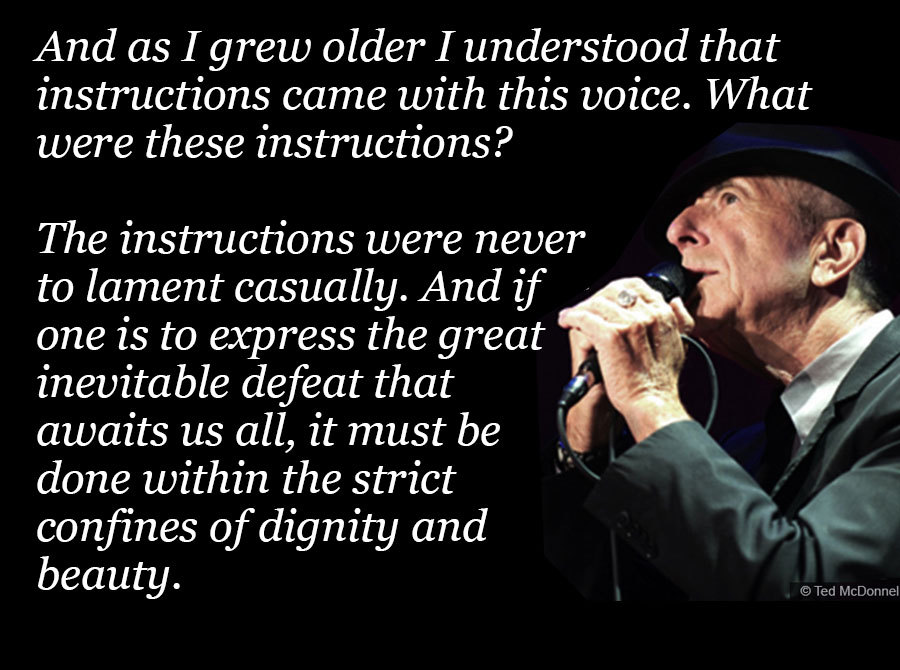

Only a week or two before Wasit’s passing at the age of 47, the final Line message I received from him was this photograph of Cohen with the quote:

“And as I grew older I understood that instructions came with the voice. What were these instructions? The instructions were never to lament casually. And if one is to express the great inevitable defeat that awaits us all, it must be done within the strict confines of dignity and beauty.”

I can’t think of a better epitaph for Leonard Cohen than that.

A longer version of this story is included in the revised and expanded 2018 edition of the author’s latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died,” which includes a 130-page bonus nonfiction section of “Rock Writings and Musical Memoirs” as well as a front cover blurb from the acclaimed author and hit songwriter, Timothy Hallinan, who said of the two interconnected novellas: “The funniest sad book and the saddest funny book I’ve read in a long time.” The ebook goes for US$3.99 and a new paperback edition is also available from Amazon for US$12.99.

Great stuff Jim, you too are an inspiration. You may indeed not be Leonard but your JIm and boy you can write.

Thank you and rock on!

Just beautiful writing mate.

Thanks a lot, John.

Lovely piece, Jim

For what it is worth I think you could pull off the suit and cowboy boots look and pull it off well. Thanks for writing and sharing this.

Thanks, but nobody could rock that look like Leonard.

Good stuff, Jim. (And I think I was an earlier denizen of many of the same parts of Montreal.)

I totally loved reading this, Jim…an amazing story…

Thanks for reading, Sue.

Loved your review. When I finally met LC, I felt exactly like you, what does one say etc. I thought I was in the presence of G-d.

Thanks, Eva. It was a very humbling experience, but he’s such a gentleman.

Very nice Jim. My introduction to Leonard was a purple plastic milk crate that held records in the first shared house I lived in after high school in Sydney. I had a flatmate who was mad about him, who also loved Dylan and his lyrics; we had dozens of Dylan albums, but Leonard also got the occasional play. It was a suburban house where roof-drinking became a fashion, and my buddy was soon growing dope up the roof – so we’d return some nights to a dark home with light leaking out from the broken roof tiles. Having four young students from school is a recipe for disaster for a landlord, but we loved the lyrics of these men. My friend Ross had a bootleg tape of Dylan playing a concert in Sydney where he was allegedly so stoned he stops in the middle of one song completely unable to remember the words. ‘Don’t Come Home With Your Hard-on’ was one of the initial gems that stood out, and ‘So Long Marianne’. Years later, the Cohen light turned on again with ‘Hallelujah’ and ‘Dance Me to the End of Love’. Maybe then I learnt he was Canadian and more about him. But that hat, that glorious straight singing style with those lovely backing vocal singers: he was something. You were lucky, and this is a lovely tribute to a formidable guy. ‘Hallelujah’ is one of the greatest songs of all time, I think. Here’s to you Jim A.

Thanks for the generous response, Jim, and sharing all those fascinating anecdotes.