The former frontman of Green on Red, Dan Stuart, discusses the group’s rise and downfall, his 15-year hiatus from the music biz and how personal tragedies inspired three acclaimed solo records and two books. Words by Jim Algie.

Some 15 albums and EPs into his checkered music career, singer and songsmith Dan Stuart would rather talk about anyone else’s music than his own, whether it’s the musicians he likes (Neil Young, The Stones, Dead Moon and the Long Ryders) or the groups he reviles (U2 and The Smiths).

When the talk turns to alt.country and how relative newcomers like Uncle Tupelo, Whiskeytown and Wilco reap most of the credit now instead of the real pioneers from the early 1980s, like Rank and File, The Gun Club and Green on Red, the LA-by-way-of-Tucson combo Dan fronted for more than a decade, does he ever feel bitter about being unsung?

“Oh hell no. No, no, no. The last thing I want is credit for starting Americana,” he quips on a gust of laughter. “It’s like the Paisley Underground. Please tell me I’m not in that. What did Groucho Marx say?”

“Why would I want to be a member of any club that would have me as a member?”

“Right. At the same time, I’ll always claim to be part of the punk movement.”

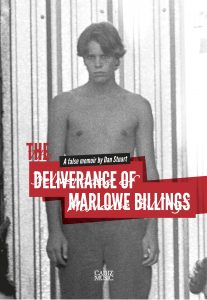

That raw and gritty approach is on full frontal display in his “false memoir” from 2014, The Deliverance of Marlowe Billings (Cadiz Music). The book is written in staccato bursts, entire chapters boiled down to a few paragraphs. There are run-ins with the police in Tucson and streetwalkers in LA, reflections on how “bands are like plutonium. They have lives and half lives,” tour tales (one involves a groupie and a spear gun), as well as some cautionary anecdotes about that occupational hazard for so many touring musicians: heroin addiction.

When the latter arrives in any musician’s memoir or biography either a fatal overdose is in the offing or it’s the catalyst for an intervention and rehab, but Dan writes in the introduction – or maybe it’s a disclaimer – that he doesn’t believe in redemption.

So much of this short book seems like a study in humility or a debunking of the rock star myth, shorn of press clippings, glamor and celebrity encounters, but embellished with a lot of vintage black and white photos of the group and plenty of black humor.

We’re sitting outside a 1972 Winnebago RV where Dan’s holed up in the oldest and most Mexican part of Tucson. The patio is made of adobe and bordered by a corrugated steel fence and mesquite trees. Dan likes sitting outside to watch the hummingbirds flit past.

He has a different take on the book. “I think there’s hubris in it, but there’s a line in the book about how devastating it is to be given a chance and you strike out, and the reason you strike out is that you don’t believe that you belong in that hustle anyway. And the hustle is something you’re against also. So you self-sabotage,” he says.

He takes a sip from his beer bottle and continues, “With Green on Red we caught the last bit of when rock criticism could still keep you signed. So the record companies would say if we just changed this or this, and get them in the right studio with the right producer, we’ll all make a bunch of money. Well that never happened… so I was just trying to be honest about it all. I don’t think we were worse than anybody else. In fact I think we were better than most other bands. I think we were as far as what rock ‘n’ roll is. It’s just this other sort of thing as a human being, where you… you’re feeding the worst part of yourself. Because you understand that the hustle you’re wrapped up in, there’s nothing exalted about it, and that’s why I say there’s no redemption. And I still don’t believe in redemption at all on any level.”

Dan goes by the name of Marlowe Billings in the book and his band-mates are all given pseudonyms. Whenever a famous musician like Neil Young makes an appearance, he’s given a nickname too.

The “Canadian drifter,” or the likes of Willie Nelson and John Bon Jovi, who shared the same stage with Green on Red at some of the different Farm Aid benefit concerts in the 1980s, probably didn’t share Dan’s sentiments when he dedicated a song “to all the farmers who ate their shotguns for breakfast.”

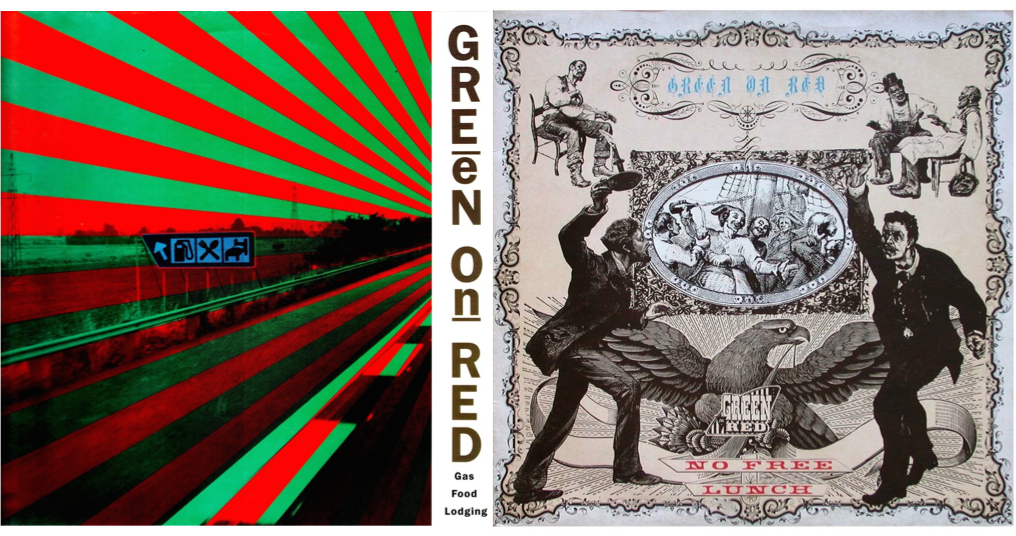

Yet it’s the kind of telling and confrontational remark – or an example of self-sabotage – that describes where the band first came from as The Serfers, breaking out of Tucson’s small but hardy punk scene to alight in LA under the new name Green on Red, during a resurgence of psychedelic garage rock dubbed the “Paisley Underground.” Such a remark may also help to explain why, even with a solid track record that included such notable albums as Gravity Talks, Gas Food Lodging and the No Free Lunch EP (three of my favourite records from the ’80s that I still listen to), and even with the backing of major labels and big-name producers like Jim Dickinson and Al Kooper, the group could never crack the Nashville country charts or the heartland rock scene.

Green on Red, from left to right: Jack Waterson, Dan Stuart, Chuck Prophet, Alex MacNicol and Chris Cacavas.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see why. The urban cowboys line dancing to “Achy Breaky Heart” or the Midwest teens watching John Mellencamp sing the praises of “Small Town” life on MTV while whitewashing the small-minded brutishness and ignorance, were never going to buy into the group’s brand of raucous, country-blues noir on such records as The Killer Inside Me, named after a hardboiled novel by Jim Thompson about an upstanding sheriff who’s also a lowdown hypocrite and murderer.

In reference to that album, Dan says, “You know, it’s funny everybody loves ‘Sister Lovers,’ Big Star three, but people really hated that record when it came out. And ‘Killer,’ it wasn’t just that awful 80s’ gated reverb on the drums, the character is completely unhinged, and if it had been a double album, because there was enough material, there were other songs that balanced that out, which didn’t make it to the record. And so it became this bombastic, paranoid, unhinged record. Having said that, if you listen to ‘No Man’s Land,’ which I did the other night when I was playing a version of it those lyrics nailed what was happening under Reagan.”

(Both the latter album and Big Star’s third record were produced in the same Memphis studio by Jim Dickinson.)

In Dan’s estimation of the group’s back catalogue, “the really bad one is ‘This Time Around,’ which is just awful,” he says with another laugh. “We got the wrong Johns brother. We should have got Andy, but we couldn’t because he was doing more drugs than us and producing these bad hair band records in LA. So we got Glyn and it was kinda like doing a record for my dad. But I shouldn’t say that because Glyn Johns has made wonderful music. In his life, I’m not even a pimple on his ass.”

Dan Stuart with the members of Twin Tones in Mexico City.

ON THE LAM IN MEXICO

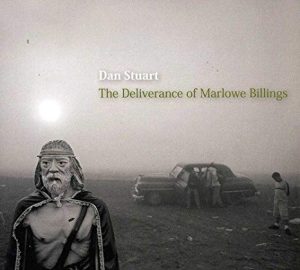

The singer’s memoir shares the same name, and a few themes, with an album that he mostly wrote in Mexico in 2010, though it was recorded in Italy and LA, with former Green on Red bassist Jack Waterson and guitarist Antonio Gramentieri handling the production chores. While some of the elements – 60s’ fuzz-rock, strains of blues, splashes of pop, folk and country complemented by punk sneers on the protest song “What Are You Laughing About?)” – drew from the same well of influences as Green on Red, there are plenty of differences too. The vocals are less abrasive and more melodic, the production more experimental, the backing musicianship by the Italian group Sacri Couri is as subtly precise and atmospheric as a film score, and the songs are never subordinate to the sort of scorching guitar solos that the great Chuck Prophet used to fire off in pretty much every Green on Red song.

At the time of that recording, Dan had been mostly out of the music business for 15 years, while living a quiet, sober, married life in Tucson and New York with his wife and son. The breakdown of his marriage led to a psych ward and then a one-way ticket to Mexico, where he began writing songs again. “I didn’t know what else to do about this mental health crisis except make another album,” says Dan, who was born in LA but grew up in Tucson.

Some of the standout songs on The Deliverance of Marlowe Billings are the heartsick ballads, like “Love Will Kill You,” which starts with the line, “It’s been 20 years of sweet hell since we heard those wedding bells.” The sadder sentiments provide some poignant counterpoints to altogether sweeter tunes like “Gonna Change,” which I imagine is about his son. (Paul Kerr from the Americana UK website lauded the latter song as “sublime… perhaps the best song Brian Wilson never wrote.”)

Some of the standout songs on The Deliverance of Marlowe Billings are the heartsick ballads, like “Love Will Kill You,” which starts with the line, “It’s been 20 years of sweet hell since we heard those wedding bells.” The sadder sentiments provide some poignant counterpoints to altogether sweeter tunes like “Gonna Change,” which I imagine is about his son. (Paul Kerr from the Americana UK website lauded the latter song as “sublime… perhaps the best song Brian Wilson never wrote.”)

That’s the positive/negative voltage which flows through that record and his next two solo albums, the harder rocking Marlowe’s Revenge (2016), recorded with Twin Tones, a popular surf ‘n’ spaghetti western band of instrumentalists from Mexico City, and The Unfortunate Demise of Marlowe Billings (2018), which stakes out a middle ground between the two previous releases. (All three are available from Cadiz Music on Amazon.)

By now we’re cracking our second or third beers and the sun is going down in a blaze of orange and pink glory behind the mountains that encircle and fortify Tucson. The desert wind is nipping at the nape of my neck, and it’s getting dark, so Dan turns on a string of lights in the patio umbrella.

Unsure if it’s a question or an observation, I say, “When musicians make a comeback in middle age, it’s often seen as some kind of cynical cash in, but some of the songs on the last album like ‘The Day William Holden Died’ and ‘Upon a Father’s Death,’ the meditations on mortality for lack of a better expression, you couldn’t have written when you were 20 or 30 or maybe even 40.”

“And certainly money wasn’t an issue,” replies Dan, chuckling again. “No, I had an idea that I wanted to do a trilogy. I just liked the word. I even like Godfather Part 3.”

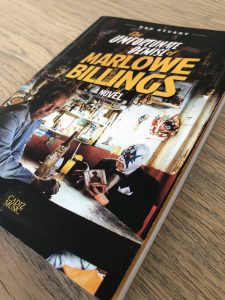

The first novel by Dan Stuart is a drastic departure from his memoir.

MEXICO NOIR

His 2018 novel (also available from Cadiz Music) is entitled The Unfortunate Demise of Marlowe Billings after the album of the same name. Like the memoir, he calls it “65 percent true.” It’s a book that hits hard on a number of different levels. Partly it’s a portrait of Marlowe’s mid-life collapse, fleeing his home and then a psych ward in New York after learning of his wife’s latest betrayal (“The obvious hatred she had for him was undeniable now, and an awful dread hugged him so tight he could barely breathe.”) to wind up in southern Mexico, contemplating suicide. All the internal dramas and backstories play out against a well-described travelogue of Oaxaca’s fiestas, rituals, beaches, history and peoples that slowly evolves into a suspenseful crime story about Mexico’s drug cartels.

Sure, many people have heard of these turf wars and horrific murders. But if the novel has any claim to relevance in the digital age it lies in telling different stories from disparate viewpoints that you’ll never see on CNN. In one of the book’s most memorable scenes, a drug-trafficker in rural Mexico shows Marlowe a poppy field that will be bled and deflowered to make black tar heroin. The former singer asks him if he worries about how many people it will kill, to which the narco replies, “No gringo I don’t. I think about how many people this crop will keep alive.”

Noir fans, or expats who have lived in Mexico, should find it interesting how Marlowe wrestles with his own fate in a country where fatalism is the norm in the grip of a genre that forbids redemption or sappy endings.

Speaking of that novel, and the final book of the trilogy he’s working on now, entitled Marlowe’s Revenge after the other solo album, he says, “That’s me to trying to write as good as I can. So there’s some literary pretensions there.” He laughs. “I’m learning my craft, but after two books it’s like giving yourself permission to make a commercial album, not in a bad way but something that’s listenable. It’s kind of a book about the Tucson I know, which has disappeared and the best way to do that is in kind of a crime noir.”

As for music, he’s said a number of times now that the last album will be his final full-length record, because people don’t listen to complete albums anymore. Though the 58-year-old is toying with the idea of other recording projects or playing with a full band again after years of touring as a duo on the Americana circuit to promote the last three albums, mostly in Europe where he has a bigger cult following than in his homeland.

“Without the drums it’s not Africa, it’s not rock ‘n’ roll. You don’t wake up the day after a gig with a hard on, you just feel drained,” he says.

With bands making less and less from album sales and a pittance from streaming services, touring is all about shoestring economics now. On the few recent occasions he has gotten to play with a full band at Americana festivals in Europe, “both places were relieved that somebody showed up and played some fucking rock ‘n’ roll,” he says.

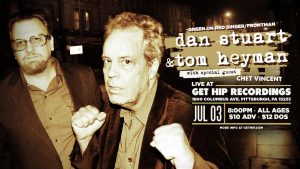

Dan Stuart on tour in Europe with Tom Heyman, a gifted guitarist, songwriter and session musician. “My luck in the music business,” says Dan, “my blind luck has always revolved around playing with great guitarists like Tom, or Chuck Prophet, Al Perry and Antonio Gramentieri.”

THREE CHORD CODA

By now it’s 9pm. We’ve been jabbering for the last five hours and drinking beer for the past three. Stars have punched silver holes in the sky and it’s getting a little cold. From a distant bar complex some melodies of cumbia and Mariachi are drifting and dancing on the breeze.

All the rock talk about playing with a full band again has fired him up. He goes back into the RV to grab his red, hollow body, electric guitar by the Japanese brand Ventura. “At least it’s old and these are hand wound pickups. You know these guitars were made in a factory in Japan and distributed all over the south in drug stores. The band Black Oak Arkansas would buy them to smash on-stage like The Who.”

He tinkers with a few riffs. “I just bought this Japanese guitar cheap and I promised myself that I wouldn’t write any more songs, because as soon as I find myself writing a song, I say to stop and just practice or learn a cover, or whatever, because I don’t wanna have another handful of songs. I’ve written enough songs, right? And I’ve got nothing more to say. But I just got this guitar and immediately I wrote a garage rock song.”

Dan Stuart during a Green on Red recording of a live concert for the German TV show Rock Palast in 1985.

He strums a three-chord riff that could have been written by The 13th Floor Elevators in the 1960s, or his old band in the 1980s, or Dead Moon in the new millennium, and talks over top of it, “All right, you heard that a million times.” Then he adds some of his reedy vocals to the mix, “These three chords changed the world/These three chords make you my girl.”

He goes up to the V chord and sings, “Yeah, this little ditty ain’t so pretty,” lets out a scream and says, “Right? Dumbest thing ever. The thing is, that’s what happens.” He stops playing. “That’s what this guitar wanted to do.”

“Every instrument,” he looks up and smiles, “Oh, a dog’s started howling… black dog howling.” Whether he’s referring to the songs by Led Zep or Nick Drake or the British slang term for depression I’m not sure. Like I said, we’ve been drinking a little.

Only a few miles away a freight train hurtles past with the whistle blowing and the metal wheels clacking against the tracks in a country ‘n’ western shuffle rhythm. I’ve heard those sounds thousands of times before, but never in this part of Tucson or under these circumstances, and that’s what makes them sound fresh again.

Songs are the same. No one has ever explained the alchemy of how they’re composed or why some musicians have that magic touch and others don’t. Most documentaries or biographies about musicians don’t even mention songwriting. Neither does his memoir.

Songs are the same. No one has ever explained the alchemy of how they’re composed or why some musicians have that magic touch and others don’t. Most documentaries or biographies about musicians don’t even mention songwriting. Neither does his memoir.

Can a guitar, as Dan claimed, demand to be played in a certain way?

Now he’s bending a few notes, strumming a few chords and mumbling, “Yeah, I love this guitar,” before launching into that garage rock riff again with a fervour that seems undiminished by time, age, geography or personal difficulties.

“These three chords changed the world…”

Sounds like rock ‘n’ punk to me.

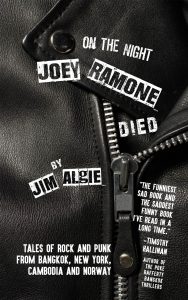

Jim Algie’s latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died,” is a story of one middle-aged musician’s mid-life crisis, as well as a collection of the author’s most famous music stories, profiles of artists like Leonard Cohen and the Pixies, and reminiscences of playing in bands during the first punk and alt.country waves. The book features a cover blurb from the popular mystery author Timothy Hallinan: “The funniest sad book and saddest funny book I’ve read in a long time.” The book is available on Amazon as a paperback and ebook.

Love the Dan Stuart. Thanks for this. Now i gotta git his latest book.

Thanks for the comments, Byron.

Great stuff, Jim. Keep on moving, Dan.

dan is definitely one of the most interesting songwriters and storytellers of the last forty years. if you ask him the right questions (which you did, jim!) you find out he’s very cute, very sensibel and very rock’n’roll all together. I missed new songs from him a lot when he was ‘gone’ for a while during the nineties and I will miss them for the rest of my life if he really stops recording.

please keep on keepin’ on, dan!

Rage against the machine eh? Or should that be dying of the light? Or blinded by it? Superb piece, as always Sir James of Algie, I could smell and hear Tucson and agree with Dan’s decision not to record another album cos everyone’s listening to lists these days. Well, fuck ’em I say, I’m off to listen to an album. May be Dan on YT or Mike on cd but they’ll never take my albums from me 55555