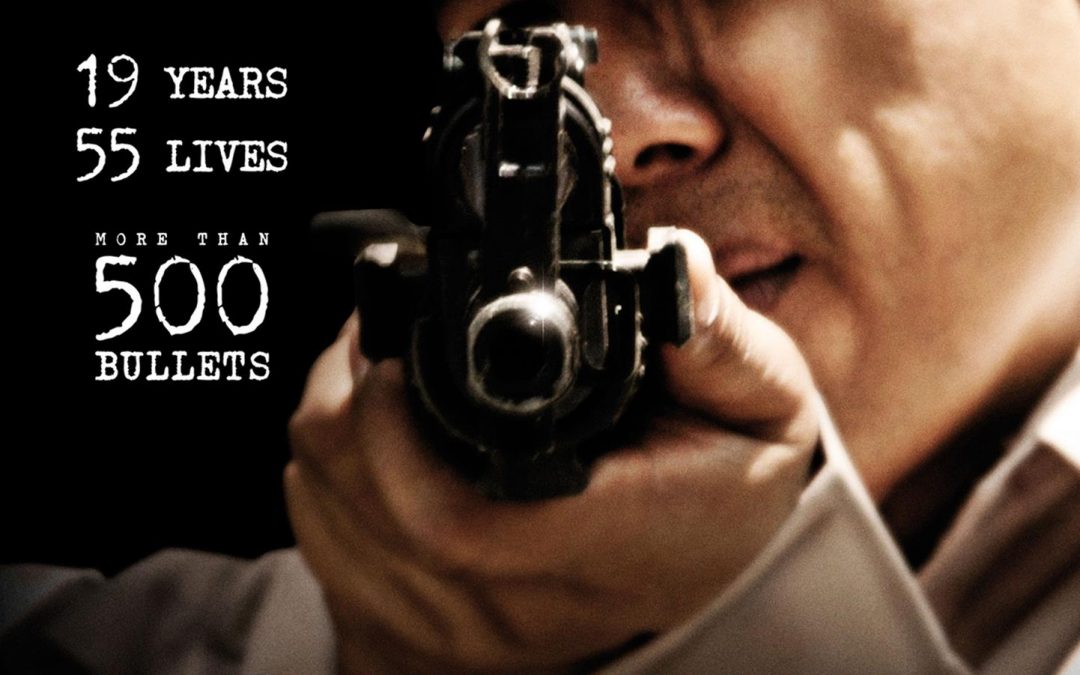

The Last Executioner is premiering in the United States on April 29, 2015, just one day before the third anniversary of the real executioner’s death.

Conflicted characters make for some of the best protagonists and hinges for dramatic tension.

Few public figures in recent Thai history were as conflicted as the late Chavoret Jaruboon. Thailand’s last executioner dispatched 53 men and two women during almost 20 years on the firing line at Bang Khwang Central Prison. At the same time, he was a practising Buddhist, a prison reformer, a family man and sporadic drinker with a thirst for beer and whiskey.

A new Thai film called The Last Executioner, which opened in Thailand in July 2014, aims to cover this man of multiple faces with an overarching plot that spans his entire life. Obsessed with early rock ’n’ roll, especially Elvis Presley, the young Chavoret began playing guitar as a boy. By his hell-raising teenage years he sported a pompadour and was touring the circuit of bars and clubs in cover bands enter- taining US troops in Thailand.

Some early scenes in the film riff on those experiences with Thira Chutikul playing the aspiring musician. For a low-budget indie movie, these flashbacks to the ’50s are impeccably detailed with all the old hairdos, clothes and dances, while Bangkok retro rockers the Helmetheads play the band.

Their tune, I’m So Happy, a take on the Beatles’ upbeat pop, becomes a theme song in Chavoret’s life. Driving to his first execution later he will put that song on the stereo and sing along. It’s not a moment of mirth, however. Nor is it tinged with that hipper-than-thou kind of irony Tarantino loves to employ. It’s more like a reverberation of youthful yearning and an echo of his past life, for regrets are keynotes in this story.

At one of his gigs, Chavoret meets Tew. Their courtship lasts about a minute on screen. Whatever sparks were kindled between them besides the embers of physical attraction, are quickly consummated as the couple are soon in bed. That scene, of loving caresses and intertwining limbs illuminated by soft-focus lighting, is one you’ve seen before in a few dozen romantic comedies. This is not a melodrama, though. Chavoret’s music career is quickly sidelined in favour of his new job as a prison guard. Against his will and finer instincts, he takes on the job reluctantly to support his family.

For a biopic, this is all very accurate. Indeed, director Tom Waller and screenwriter Don Linder, after meeting by accident at a dinner party, have favoured fact over fiction, but not at the expense of dramatic economy.

Sitting in his office at De Warrenne Pictures in Bangkok, Waller said the executioner first came to his attention after he read my front-page obituary for him in the Bangkok Post in 2012. “After Chavoret passed away Don and I approached the family to get their permission to make a film about him, based on the family’s recollections of him and from material we gathered from the public domain and historical sources, and also from government sources like the Department of Corrections.”

The screenwriter, he said, also used notes from his interviews with Chavoret and met some of his old colleagues and bandmates to forage for more scraps of material. “So Don had to cobble together all these interviews and third-hand sources into the screenplay,” Waller said.

In spite of all the realistic details, Waller did not want to make a documentary. Even the flash-forwards to Chavoret appearing on chat shows and quiz programmes have been reshot with rising star Vithaya Pansringarm playing him in his later years when he became an unlikely celebrity.

Biopics require a great deal of compression so a person’s entire life can be condensed and distilled into 90 or 100 minutes. Inevitably, some of Chavoret’s complexities had to be left out of the film. His final position at Bang Khwang as the Chief of Foreign Affairs, overseeing more than 700 foreign inmates, is not mentioned. Nor is his role as a facilitator for programmes to help prisoners with cataracts and Aids.

THE GHOSTS OF GUILT

Perhaps the most ingenious invention in Linder’s screenplay is the presence of three men who are gradually revealed to be the ghosts of Chavoret’s guilt and the voices of his conscience. Sometimes mocking and sometimes menacing, the main tormenter is played with panache by David Asavanond, a French-Thai actor who won three major awards for best actor in Thailand for his role in Countdown, when he played a psychopathic drug dealer supplying Thai teenagers with high times and low blows during a New Year’s Eve party in New York.

His scenes in this biopic about Thailand’s last executioner are not executed with any over-the-top histrionics, nor campy sound effects or villainous cackles. As Linder explained it, the inspiration for these make-believe menaces came from Thai folklore and some of the protagonist’s personal experiences. Borrowed from Hinduism, Yama is the lord of the dead and the judge of the deceased. He has two assistants.

On his deathbed, Chavoret saw three otherworldly figures approaching him. That anecdote, relayed by his loved ones to Linder, was one of the reasons underlining the screenwriter’s decision to portray these surreal figures in a realistic way. The other was a story Chavoret told him about a visit to a fortune- teller at an early age when she said his life’s work would revolve around death.

During his research, the Chiang Mai-based screenwriter came upon two websites where Thais related their near-death experiences in English. “What came out of those was fascinating, that Yama and his assistants are like normal guys. And in one near-death experience they talk about them taking someone into an office building and up on an elevator. That helped me put it in perspective, that it was just real stuff. And so David’s character evolved as a haunting character but somebody who is also real.”

MANY FACES

To play such a multifaceted character as the Thailand’s last executioner, Vithaya faced the most daunting challenge of his four-film career. His previous roles as a crime-solving monk in Mindfulness and Murder, and as a sword-wielding, karaoke-loving policeman in Only God Forgives, starring Ryan Gosling, required little in the way of emotional elasticity. They were static characters, sullen and introverted, who remained a little thin even as the plots thickened and the action broiled.

Besides sharing a few physical characteristics, Vithaya and Chavoret share a more important quality: cool facades masking warm personalities. In person, the gregarious actor, who helps to run a ballet studio with his American wife in Bangkok, projects the exact opposite of the taciturn tough guys he plays on screen.

Alternately cocky and modest, amusing and earnest, the actor embodies many of the dualities that made the movie’s protagonist such a complicated character.

To get into the part, he read the executioner’s memoir and studied DVDs of his interviews. He noted how Chavoret wore his watch on different wrists at different times, and how his lower lip protruded a bit when he was interviewed, as a way to delve deeper into the role.

Before the first day of filming began, he called Chavoret’s only daughter, Chulee, to request that she ask her father’s spirit for his blessing. “I got so much positive energy and inspiration from her love for her father,” he said over coffee at a Thong Lor cafe not far from his family’s Rising Star Dance Studio.

Vithaya has no formal training as a thespian. Unheard of in the Thai film business, he did not land his first major part until he was almost 50. He credits some unusual sources for influencing his acting style: studying kendo, the art of Japanese sword fighting, for almost 30 years; working for a decade in marketing and distribution with Amway products; and, “Look at this 55-year-old face with all the holes in it. It’s like an old tyre.” He laughed. “When they were doing my make-up on the first day, they tried to make my face look smooth. Tom Waller came past and told them to leave all the holes showing.” He laughed again.

Vithaya’s understated performance was lauded at the Shanghai International Film Festival, where he won the Golden Goblet for Best Actor. The movie, meanwhile, made it to the final 15 for Best Film. After thanking the jury and the cast and crew, he hoisted the award heavenwards and, speaking in Thai, offered it to Chavoret. (The man who grew up wanting to be a rock star would have been thrilled by this sprinkling of stardust on his posthumous legend.)

One of Vithaya’s finest moments in The Last Executioner comes when a young man is courting his then-teenage daughter. Chavoret mimes using the acoustic guitar as a machine-gun and asks the suitor, in a half-mocking, half-serious way, if he knows what line of work he’s in. It’s the kind of bang-on characterisation that those of us who knew him will cherish as the genuine article: funny, loving, a little scary and fiercely protective of his family all at once.

TRUE CRIME CENTREPIECE

The centrepiece of the film, which also became an important component of Chavoret’s 2006 English-language autobiography, The Last Executioner, is based on a true case of kidnapping in rural Thailand that went horrendously wrong after the young boy died.

Both the kidnappers were sentenced to death. The man confessed but the woman, her name has been changed to Duangjai, claimed she was innocent. This is the film’s most harrowing scene. Even as they are led into the death chamber, he screams that she is innocent as

Duangjai weeps and pleads for clemency. The execution goes as badly as the kidnapping. This is not an excessively gory film, but Waller and Wade Muller, the director of photography, made sure that the Buddhist rituals and bloodshed are depicted in a take-no-prisoners way. Referred to in Thai as the “room to end all suffering” — this is not death row in the Christian state of Texas — the condemned men and women are led in while blindfolded and holding three sticks of incense, a lotus blossom and candle, as if they were going to pray at a temple.

For the first time in the film and in real life, Chavoret develops a cyst of doubt about the legal system that turns malignant in his marriage. Even his by now middle-aged wife (Penpak Sirikul makes the most of a small yet vital role) cannot believe he’s executed a woman that many believe is innocent. She also resents that the press have followed him back to their house.

At last his work has invaded the home front.

KARMIC KICKBACKS

The Last Executioner is a film that could have only come out of Thailand. What prevents any comparisons to Western prison dramas such as Dead Man Walking or The Shawshank Redemption are all the folkloric accents and Buddhist beliefs. As Chavoret wrestles with his karma, praying before spirit houses and freeing birds from cages, he also searches for his soul. These distinctly Thai touches are handled without any of the heavy-handed sledgehammers of “Thainess” (too often a euphemism for quaint obsolescence).

Waller’s previous films, such as Monk Dawson and Mindfulness and Murder, have all had “themes of guilt and sin” running through them, he said. That goes back to his childhood. Raised at a Catholic boarding school in England, the Thai-British filmmaker’s mother was a Buddhist. So they would go to Wat Thai in London and make merit together.

Lest anyone think they are in for a celluloid sermon, the film’s most comical interludes belong to the illustrious actor Si Tao. Now 89, he plays the abbot who Chavoret consults at a temple, amid swirls of incense smoke and Buddha images burnished with candlelight.

In one chuckle-worthy scene, the abbot tells Chavoret that he once wanted to be a singer too, and in a craggy voice sings and plays a little air guitar, before he catches himself. “Oops, almost sinned,” he cackles.

THE VERDICT

What may be seen as a virtue for critics and more discerning movie-goers, but a vice for marketers, this biopic about Thailand’s last executioner is almost impossible to pigeonhole.

It has its thrilling moments, in the jail and the death chamber, but it’s not really a thriller. It has its share of familial elements, but is not really a family drama (Chavoret’s two sons are barely shown at all).

It certainly has its artier moments, and looks gorgeous for a film shot on digital, rich in the colours of whichever era the time-traversing script moves, but it’s not your usual repertory-cinema fare either.

In a Thai film market heavy on hackneyed horror, screwball comedies and soapy love stories, The Last Executioner is an anomaly. At home, it deserves a wide audience, but moviegoers may be scared away by some of the more macabre subject matter and the superstitions surrounding it. Abroad, the movie could do well, and the subtitles are superb, though the political incorrectness of dealing with capital punishment in Buddhist terms without explicitly condemning it may be off-putting for some.

In either case, the jury is hung for now.

While trying to sum up this genre-jumping film, what can one say?

Ultimately, and perhaps surprisingly, the movie is more about life than death, more about family ties than criminal escapades, more about remorse than redemption and, as Chavoret himself repeats throughout the movie, as he did many times in real life, he was only doing his duty, for which he was paid an extra 2,000 baht per execution.

That duty was to his family. What better reason is there to kill?

Jim Algie has written about the late executioner in his non-fiction collection, Bizarre Thailand: Tales of Crime, Sex and Black Magic, as well as in his short-fiction collection, The Phantom Lover and Other Thrilling Tales of Thailand. This story originally appeared in the Sunday Brunch magazine of the Bangkok Post on July 6, 2014.

Recent Comments