On the first anniversary of the passing of Anthony Bourdain, Jim Algie looks at the spiking suicide rate in the West and how a man who survived a leap from the Golden Gate Bridge is leading a revolution in suicide prevention and awareness.

My brother and I were nine or ten years old and out riding our bikes on a Sunday afternoon, when we came across a huge throng of people standing outside an apartment building.

As we put our mustang bikes with the banana seats up on their kickstands an ambulance with lights flashing and siren screaming pulled up, followed by a police car.

In our quiet, middle-class neighborhood this kind of commotion was rare.

One of the few advantages of being a small kid in a big world of large adults is you can sneak your way through any crowd in record time.

When we got to the frontline of bystanders on the grass of the apartment, we saw a man lying on his stomach in the garden.

We exchanged some whispered speculations, “Is he dead?” “You think he jumped off a balcony?” “What’d he do that for?”

This was the first corpse either of us had ever seen. But there wasn’t any blood. It wasn’t scary or grotesque. In a way it looked natural. All I could think was this man had returned to the earth, like that line from the Bible we learned by heart in Sunday school: “Ashes to ashes and dust to dust.”

Over dinner that night I decided to ask my mom what she thought of the scenario.

She sighed and put down her fork. “Oh Jamie, we shouldn’t talk about this at the dinner table.”

So I brought it up in her car on the way to hockey practice and while shopping at Safeway and after watching TV at night.

But she didn’t want to talk about it then either.

As it turned out, neither did anyone else.

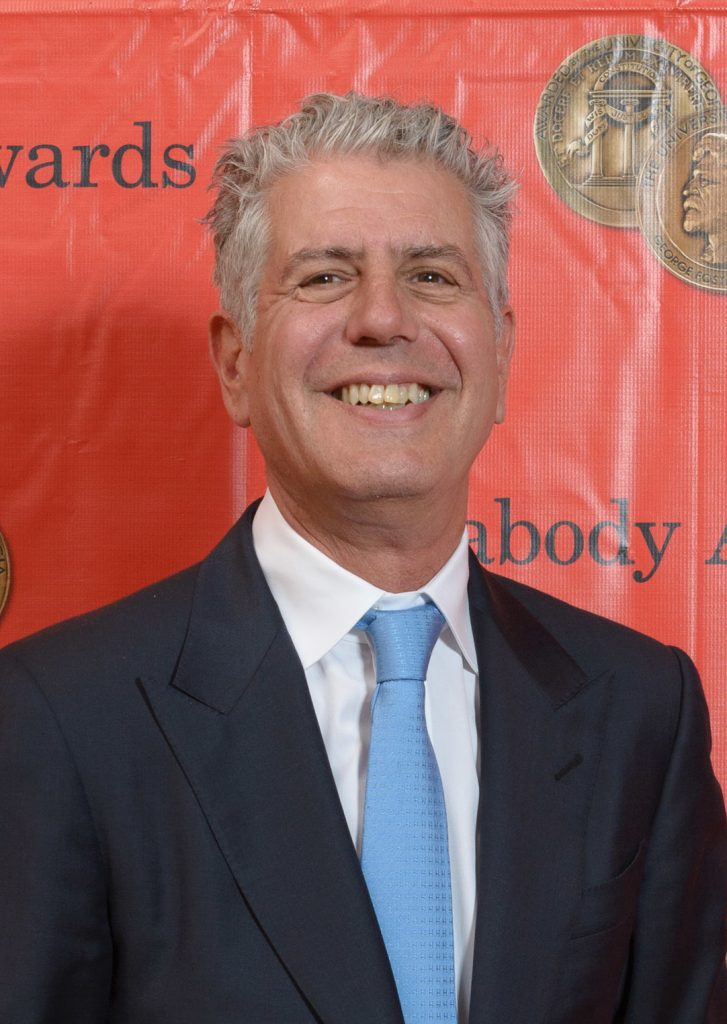

Anthony Bourdain at the 2014 Peabody Awards for “Parts Unknown”.

CELEBRITY SUICIDES

Over the last 30 years or so, I’ve played a lot of shows with rock stars like the late Chris Cornell from Soundgarden, and interviewed plenty more famous actors, supermodels, and a couple of celebrity chefs, though never Anthony Bourdain.

From those experiences I’ve learned a few things about the pros and cons of stardom.

The late Chris Cornell playing the Montreux Jazz Festival in 2005. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

It takes an enormous amount of ego to put yourself up on stage or in front of a TV camera, which is powered by an equally enormous amount of insecurity. For it takes a lot of weakness to seek out the approval of big audiences to validate yourself. These strains of egomania and insecurity are only enlarged and aggravated by success.

The successful rock musician or celebrity chef has to do constant interviews where they talk about themselves and their work and their latest shows and tours. They’re on podcasts. They’re on TV. They write blogs. They’re all over social media.

When they meet their fans, they have to keep talking about their work, their lives, their TV programs, their recipes and songs, over and over again.

Is it any wonder that the celebrity, hounded by the paparazzi and dogged by fans, wants to find an escape hatch? Could be an isolated mansion in the Caribbean. Could be drugs. Could be multiple sex partners. Could be any self-indulgent activity.

In a long nonfiction story called “My Close Encounters with Rock Stars” from my latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died,” I take the reader backstage to the aftermath of a Pearl Jam show in Bangkok that I was reviewing for a local newspaper back in 1995, when they were one of the biggest bands in the world.

“Off to one corner of the dressing room stood Pearl Jam’s front man with his bodyguard or personal assistant. I got close enough to hear Eddie Vedder try to excuse his lackluster show by saying, “At first I couldn’t relate to the crowd, then I couldn’t relate to the band, finally I couldn’t even relate to myself.”

Amid all the backstage revelry, the drinking, laughter and chit chat, the most famous man in that room also looked the most miserable and uncomfortable.

And you wonder why guys like Kurt Cobain and Chris Cornell from Soundgarden and Chester Bennington from Linkin Park end up killing themselves? There’s part of your answer. You get to the point where you can’t relate to the crowd, your band, or even yourself. And where are the consolations for all that misery and alienation? Not all the fawning fans with their mindless adulation, not all the parasites who want to use you to look cool or get them a record deal, not the fickle-as-fuck industry and show-biz people who will disappear as soon as the newer and cooler bands start outselling you.

No, the consolations while on the road tend to come in a bottle or a syringe.

Imagine a secretary or an electrician saying that they couldn’t do their job because they felt alienated from their colleagues and themselves. Would that excuse fly? But rock stars and other celebrities are granted all sorts of special privileges, as befitting their supposed beauty, genius and talent, including the permission to be that self-indulgent and have someone around to pamper to their every little neurosis.

That is unhealthy in the long run.

To be fair, if a guitarist or a drummer has an off-night most of the crowd will not notice. If the singer has a bad show then it’s going to be a letdown for the majority of the fans. That’s an extra burden which front men and women have to shoulder.

I don’t want to psychoanalyze – and thereby trivialize – the suicides of Kurt Cobain, Chris Cornell and Chester Bennington. So I’m only framing this as a question, because I don’t have any answers either. But if you have the courage, the angst and the ego to get up on stage and scream your heart and lungs out about all your deepest troubles, what would happen if all those woes and urges backfired so you were on the receiving end?”

Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

AVERAGE CELEBS

In one crucial respect, Anthony Bourdain, Keith Flint from the Prodigy, Robin Williams and Chris Cornell were all alike and all very average: they are part of the largest at-risk group of those taking their own lives: white, middle-aged males from the West.

That number has risen in recent years.

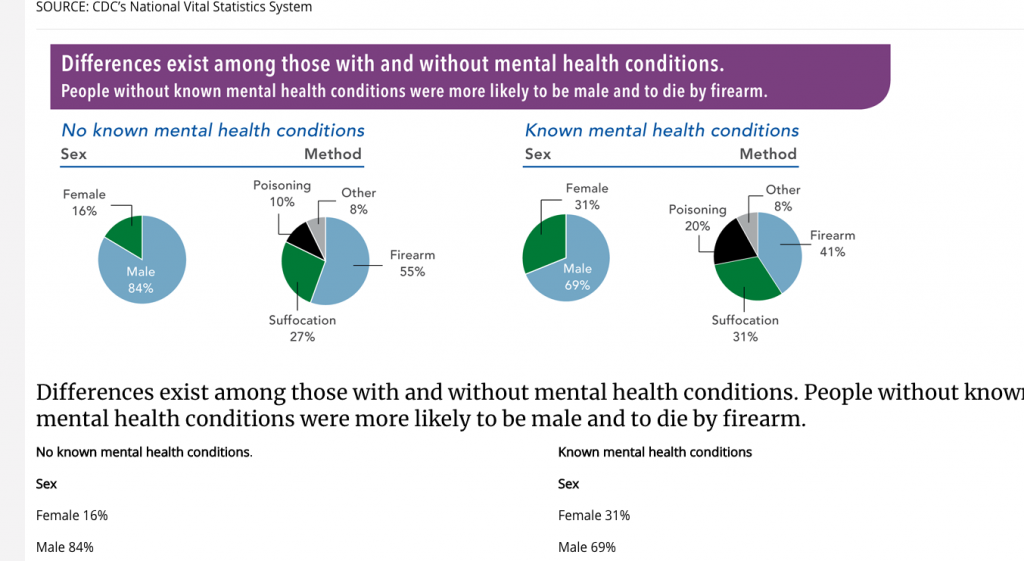

In the same week in June 2018 that Anthony Bourdain and Kate Spade took their own lives, the Centers of For Disease Control and Prevention released a report saying that 45,000 Americans committed suicide in 2016, a number that has risen by 25 percent since 1999. Some 77 percent are male.

Screen shot of the CDC report.

Mental-health professionals have speculated about a variety of causes, ranging from a rise in depression to a lack of treatment facilities to lax gun laws in certain states, rising divorce and unemployment rates, to the isolation of living in a digital world where one is so often disconnected from family and friends.

It’s a vastly different world that we inhabit since my brother and I first came across the man who had turned a garden into his temporary grave some 40 years ago. Certainly there’s more awareness of mental health issues; there are more suicide hotlines, and more groups for relatives who’ve lost a family member; there are also many more antidepressants on the market.

One thing that hasn’t seemed to change much in those four decades is the taboo nature of this topic and the stigma surrounding such mental-health issues. I don’t know of any real data on the subject, and I can’t imagine many people wanting to answer such a survey.

But I do know plenty of fans of Soundgarden, and the Prodigy and Anthony Bourdain, and here’s the number of discussions I’ve had about the whys and wherefores of their deaths.

Zero.

Anthony Bourdain chows down on street food in Hanoi’s Old Quarter. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

Has the dialogue about depression and other such issues changed from what many see as a form of insanity that somebody should just snap out of, or are they seen as the largely treatable diseases that they are?

If you think the stigma has changed, try this. The next time you’re feeling so lethargic and pessimistic and self-loathing that you can barely get out of bed to go to the bathroom, call your boss and tell him that’s why can’t come to work.

Imagine that being written down in your HR files. Imagine your colleagues gossiping about you.

Without this fundamental change of perception and without a dialogue opening about what remains a taboo topic, the suicidal and the depressed will bear their burden in silence and shame, too fearful to confide in anyone who might be able to save them, or seek the help they need, and the suicide rate will continue to spike.

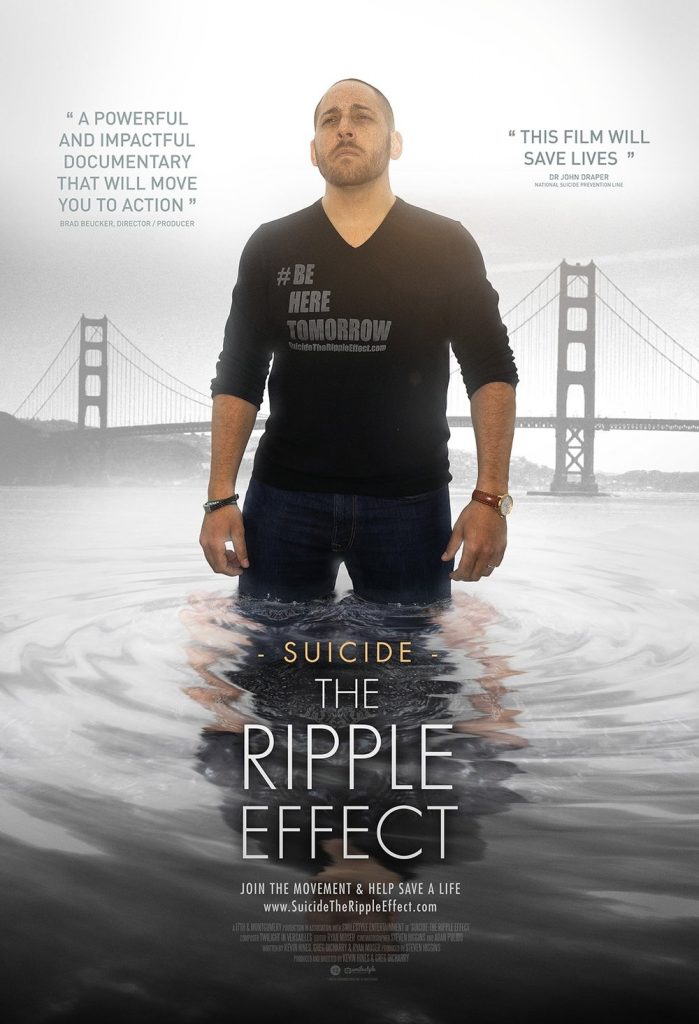

Kevin Hines survived a leap from the bridge to become a leading advocate for mental health awareness and suicide prevention.

SUICIDE SURVIVOR

Looking up to stars and celebrities is for the young and the simple-minded. It doesn’t mean I respect the music of Kurt Cobain or the culinary genius of Anthony Bourdain any less. But I’ve met too many stars or wannabes to realize that they’re mostly average people with a few special gifts who also had a lot of luck and timing on their side.

I look for different qualities in my heroes now.

One such man I look up to is Kevin Hines. In the year 2000 he became one of only a few people to survive jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge.

His story is one of the most dramatic parts of the profoundly moving and deeply disturbing 2006 documentary, The Bridge. In the film, and during his lectures, he talks about how when his hands left that railing he thought of it as the biggest mistake of his life, and that he realized he didn’t want to die.

It’s the kind of insight very few people have lived to share. And it makes you wonder how many other troubled folks, who had just kicked out the chair or taken that plunge, felt the same.

A harrowing scene from the 2006 documentary The Bridge

One of the most controversial parts of the documentary is that the director, Eric Steel, filmed 23 suicides over the course of a year. It sounds exploitative and perhaps it would be if he hadn’t juxtaposed the footage with interviews showing the survivors talking about their loves ones in heartbreaking detail.

The story of Eugene, a depressed yet likable young Goth guy who tried many times to make a fresh start, is especially tragic. Only a week after his fatal plunge a letter arrived from a comic-book shop offering him his dream job as the manager.

It’s like that with the suicides I’ve known too. I wish they’d reached out one last time. I wish I could have reassured them that life always turns around and that if you’ve reached middle age that means you’re strong and you’re a survivor. So why not keep going?

That’s what Kevin Hines did. He survived that leap from the bridge and his ongoing bouts with bipolar disorder, to become an advocate for mental-health issues, who has shared his experiences at veteran centers, at the White House Dialogue on Men’s Health, and at thousands of colleges high schools around the world.

In 2018, he co-wrote and co-directed a documentary about these experiences entitled Suicide: The Ripple Effect. Like The Bridge, the film shows how those close to the deceased are affected by their demise. The survivors suffer from relentless guilt and confusion for the rest of their lives.

Yet the documentary also shows the positive repercussions that Kevin’s talks and his honesty have had on others, how many lives he’s saved and how many of the desperate he’s inspired to seek treatment for what ailed but could not kill them.

“You are your brother’s and sister’s keepers and if you see someone in terrible mental and emotional pain please say something,” he says to an audience in the film. “And if one of you is suffering and you’re quiet about it, today, tomorrow, the next day, ask for help. Tell the truth about your pain because it’s the only way to purge it from your soul. ”

Above all, Kevin realizes how lucky he is to still be alive, and he wants to share his gratitude with others.

That’s why the film’s hopeful hashtag is #beheretomorrow.

Jim Algie’s latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died,” deals with rock stars enduring fame, substance abuse, mental illness, mid-life crises and staging late comebacks in a youth-centric business. The book is available on Amazon. He is currently working on another collection of writings called, “Never Repeat Any of These Stories at the Dinner Table.”

Excellent article on a difficult topic. Thanks for that.

Where nothing, nothing matters, not yesterday not tomorrow, only the pleasure and triumph of this instant moment that never, never lasts. Eternity.

I like how you began with that personal anecdote to show how children are naturally curious about everything but adults don’t want to talk about painful subjects. I think in Robin Williams’ case, he was facing slow but inexorable deterioration due to Parkinson’s. But depression too, of course. At least now it is within our frame of reference to look at it as a medical condition…