For a guy who banged out his riffs, odes and elegies on a typewriter instead of a musical instrument, Hunter S Thompson composed one of the most accurate descriptions of the music industry I’ve ever heard, calling it “a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where pimps and thieves run amok and good men die like dogs. There is also a negative side.”

To be fair, there’s also a very positive side. Through the music biz I got to meet so many cool people, from Hell’s Angels to fetish models and rock stars, and have so many strange experiences, like directing a couple of music videos, that I never would have had the chance to do in any other walk of life.

Here’s the backstory on my brief career as a music video director.

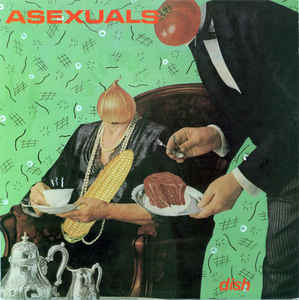

The surrealistic cover of Dish.

When we were getting ready to release the Asexuals’ third album, Dish, at the end of the 1980s, we faced a dilemma that is still common to many bands recording for small labels: there was almost zero budget to promote the album. About the only thing we could count on was that the label would send out copies of the record to campus radio stations across Canada, as well as some newspapers and music fanzines.

The label would help to organize a launch party, but they wouldn’t pay us any money up front to launch a tour to drum up more album sales and make the rounds of the college radio stations to do interviews and plug the record.

The only other promotional vehicle driving record sales was music videos. By then, after Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” raised the production stakes to Hollywood levels and the budgets, music videos had become like miniature movies, with story lines, exotic locations, luxury yachts, dozens of dancers and extras.

Among underground groups, or any offbeat band claiming to have an iota of integrity, MTV was a three-letter curse word, and making music videos considered a necessary, if totally uncool, evil, because the video channel and its Canadian equivalent, Much Music, had a few alternative shows. The sad truth was that you had more chance of getting a video shown on one of those programs than facing the Vegas-long-shot odds of trying to crack the mainstream AM or FM radio markets.

Except we had no budget to make a video and we didn’t know a music video director or any filmmakers in Montreal anyway.

Then a bolt from the wild black yonder struck, or maybe it was a toke of what actor and musician Alain Goulem called “Nepalese tobacco enhancer,” and the answer came to me in a flash.

All I needed was a hundred dollars to make some brilliant videos that would be sure to missile-launch our new album into the starry cosmos of the MTV solar system.

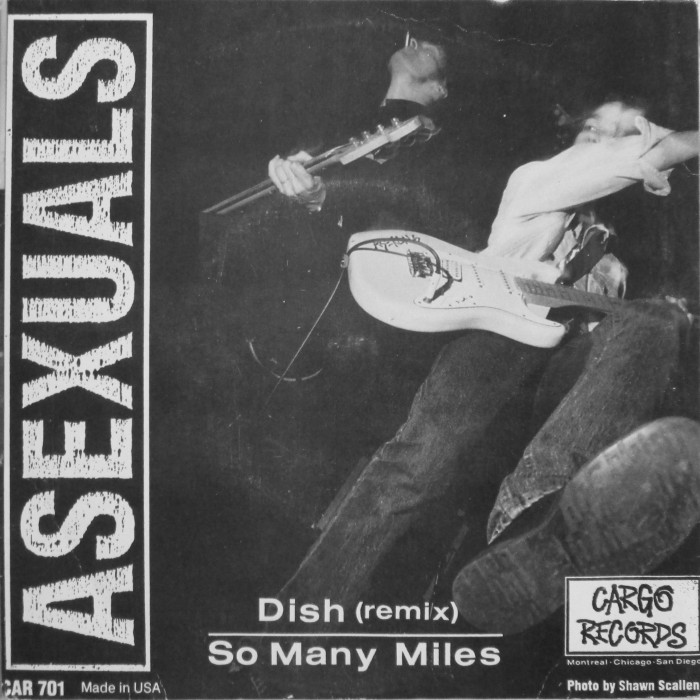

Blake Cheetah (left) and Sean Friesen (right) kicking out the jams.

Our man at the label, let’s call him “Ernie,” did not quite see it that way, to put it mildly. He tried to blow me off and straight out the front door of his office with a typhoon-force burst of laughter. “Let me get this straight. You want me to give you a hundred bucks so you can make three music videos?” He slapped the desk, touched his index finger to his forehead in a gesture of insanity, and sniggered some more.

“Yeah, that’s the deal.”

Using my stage name that everyone called me back then, he said, “But I know you, Cheetah, you’ll squander the money on booze and drugs.”

“That was the old Blake Cheetah, who has now changed his spots. Okay, let’s make it four videos.”

In the end, the sheer lunacy of anyone thinking they could make four music videos for a hundred bucks, and my repeated promise to pay him back the entire amount if I didn’t come through, wore him down.

Of course, he had no idea what I was up to. Neither did the rest of the band, like lead guitarist and sometimes lead vocalist Sean Friesen, who was equally amused by what he thought had to be a hash-pipedream. John Kastner, the former singer of the Asexuals now with the Doughboys, whom I admired for being a tireless worker and self-promoter, also thought that this music video director plan sounded like the outline of a comedy sketch.

Looking at it from their perspective I guess it didn’t seem like the most likely prospect. Here was a guy with the absurd stage name of Blake Cheetah who exuded almost no flair for, or interest in, self-promotion, who couldn’t be bothered to move his own equipment most of the time, let alone help the rest of the band move theirs – and now he was promising to make four music videos on the scrawniest of shoestring budgets?

When you can talk or write about yourself in the third person it’s a sure sign that show biz has begun to warp your character.

Blake Cheetah, dubbed the “Keith Richards of the bass guitar” and a “local legend” by the Montreal Gazette, at Shortman’s Diner (left) and from the Asexuals’ album Dish.

THE DREAM FACTORY

A few months before that I’d been walking through a shopping mall in Montreal full of shiny floors, gleaming chrome and glinting mirrors. Each of these bright surfaces was supposed to reflect back a newer, brighter version of yourself, if only you could afford these perfectly lit products that would surely add luster to your dull life.

But if you looked closer at this House of Mirrors you could see that the mannequins had no eyes, the escalators were full of sharp teeth and the place was chilled to the freezing point of a morgue. There’s no warmth in a mall and almost no smells either. Sterile and lifeless, these are the clinics and labs of consumerism.

And the shoppers, all the lifeless shoppers, shuffling around, dead to the world and everyone around them, could give you flashbacks of Dawn of the Dead (director George Romero said he was trying to make a statement about mindless consumerism).

Michael Jackson’s Thriller changed the game and raised the bar for music videos

On one floor of the mall was a shop with a stack of video monitors in the window. The top monitor showed a little girl dressed as an angel miming to Madonna’s “Like a Virgin.” The monitor below that showed a group of drunken frat boys in togas playing air guitar to “Louie Louie.” In another video a young Asian guy dressed as Michael Jackson was moonwalking to “Billie Jean.”

This was hideous and it was hilarious. These were the greatest and the lamest music videos I had ever seen.

The store, called A Star Is Born or something like that, was a warped dream factory where anyone could make their own music videos by lip-syncing to real songs, or splice in their own vocals, to live out all their frustrated musician fantasies or pretend they were superstars for an hour, then bring the videos home to play for their friends.

The videos were sad – sad reminders of how few people attain any of their dreams of becoming celebrities – and they were creepy too. What sort of parent lets their little girl mime to risqué Madonna songs? Was some mom or dad encouraging their children to live out the parents’ thwarted ambitions?

My plan to make the music videos was simple. I would get their tech guy to play the tracks we’d chosen off our new album while we pretended to play along to them in the studio and he recorded them on video.

For video backdrops, the studio had a choice of rear projections: a moving roller-coaster ride, a gushing fountain with blinking lights, a golf cart driving through botanical gardens, a blimp coasting over mountains and some other hokey crap I can’t remember. Instead of having one background I told the engineer to just flip between them while using every one of his cheesy effects, like the mirror ball, the strobe lights, the slow-motion effect, and all the multi-colored spotlights.

Here’s another positive side of the music business: it can be great fun at times. While normal people were out working in offices, factories and supermarkets, here we were miming along to our songs, play fighting in the middle of them, sneaking off to smoke some “Nepalese tobacco enhancer” in the parking lot, and generally living in a beautiful and innocent state of stunted and protracted adolescence.

Living out our own rock and punk star fantasies, we were no different from any of the other daydreamers who came here for a reprieve from their tedious lives. As professionals doing this in search of a more lucrative and long-term career, we were more ridiculous and delusional than any of them.

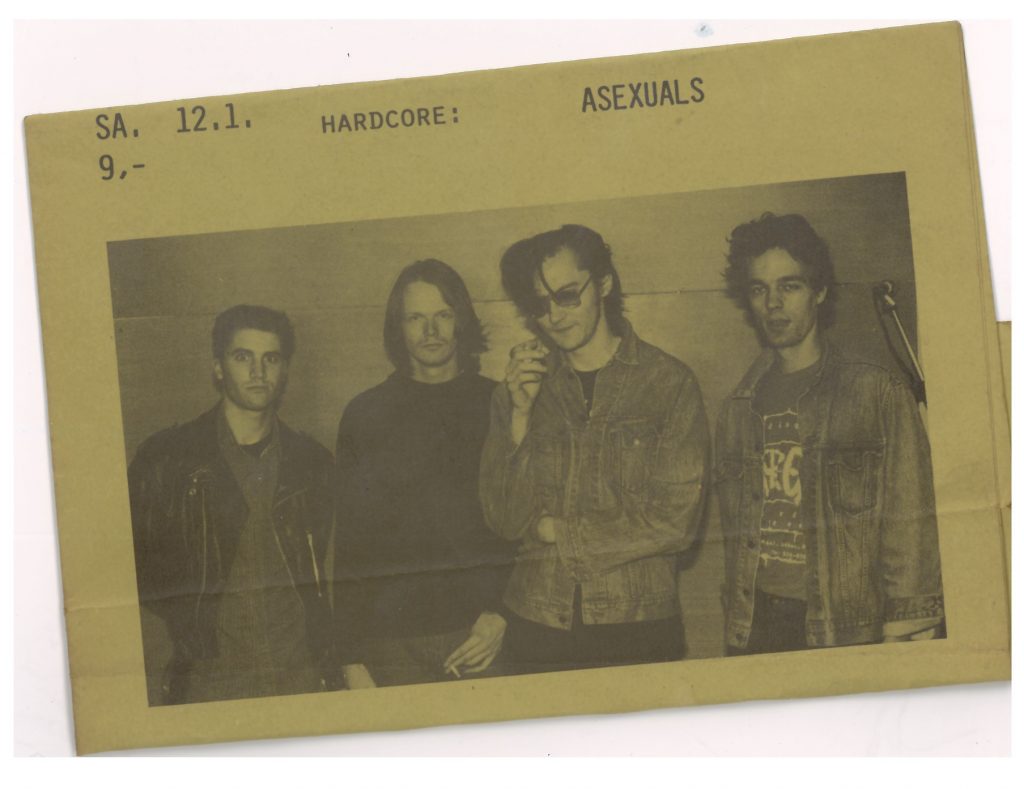

From left to right, the Asexuals were on the Dish album: Paul Remington (drums), TJ Plenty (lead vox and guitar), Blake Cheetah (bass and music video director), and Sean Friesen (lead vox and guitar)

ALBUM AND VIDEO LAUNCH

At the launch party for the album, held at Les Foufounes Électriques (“The Electric Buttocks”), a big club in downtown Montreal that is still running, some 300 fans cheered wildly after the first video, while a few dozen elitist killjoys stood around the bar drinking and perfecting the stiff poses and airs of indifference that come with being way too cool to pay any attention to a mere hometown band.

Even I was stunned by how professional the first video looked. I had done zero post-production on them, but by having the tech shif constantly between all the different backdrops and the different special effects, the videos looked as if they had been professionally edited. In this carnival of kitsch, the roller-coaster, the botanical gardens and the fountain, contrasted with flashing mirror balls and strobe lights, made a complete mockery of music videos, which was what I’d been shooting for in the first place, thereby turning the songs into an ironic counterpoint and protest against the false sentiments of pop music, in general, and the phoniness of the music video medium, in particular, as if to say, Come on, MTV, get fucking real. No band plays songs in the middle of a desert without amps, mics or electrification and then cavorts with half-naked models who have perfect hair and makeup and who just happen to be hiding amongst the sand dunes waiting to be ravaged by hair-metal rockers in leather pants.

From the VH1 special “The Thirst Is Real: The All time Best Music Videos Set in the Desert.”

Even Ernie was complimentary, shaking my hand, buying me beers. From his perspective as a penny-pinching music company man, producing four music videos for a hundred bucks was a major feat of economizing.

The trouble was, the second video looked pretty much like the first one, the third was more of the same, and by the time the fourth one had ended, the storms of applause had died down to a pitter-patter of halfhearted claps. Like at every other gig in the history of the world some dimwit yelled, “Play a song!”

In the end, the videos got some airplay on Much Music. That I remember. I don’t think we made it onto MTV though, which only had one show dedicated to alternative rock back then anyway.

Whatever.

It was a great lesson in how, no matter what you’re doing in the arts and entertainment world, or in any small business, you can always find cool ideas that can be done cheaply. Or to put it another way: financial necessity is the springboard of innovation.

It was a great lesson in how, no matter what you’re doing in the arts and entertainment world, or in any small business, you can always find cool ideas that can be done cheaply. Or to put it another way: financial necessity is the springboard of innovation.

So keep your eyes open and your ears pricked up. Even your average mall can be a warehouse of potential ideas that are worth far more than a big budget and little creativity.

Best of all, the four videos have never shown up on Youtube to cause us any retroactive embarrassment. And even better, the video recording session at A Star Is Born only cost 60 bucks. I pocketed the other 40 as my producer’s fee and, as Ernie had correctly guessed, promptly and righteously blowing it on beer and “Nepalese tobacco enhancer.”

All in all, it was a good take for a few hours of amusing work in the crass and cutthroat music business run by pimps and thieves, as Hunter S Thompson so acutely observed, where musicians so rarely get the last laugh let alone rake in 40 percent of the proceeds.

(In lieu of those videos here is a fan video for the title track from Dish, a bleeding-heart love song set to the bloody climax of Scarface. The latent music video director wishes he’d thought of that.)

Bands looking for an affordable music video Svengali can contact Blake Cheetah at jim@jimalgie.club.

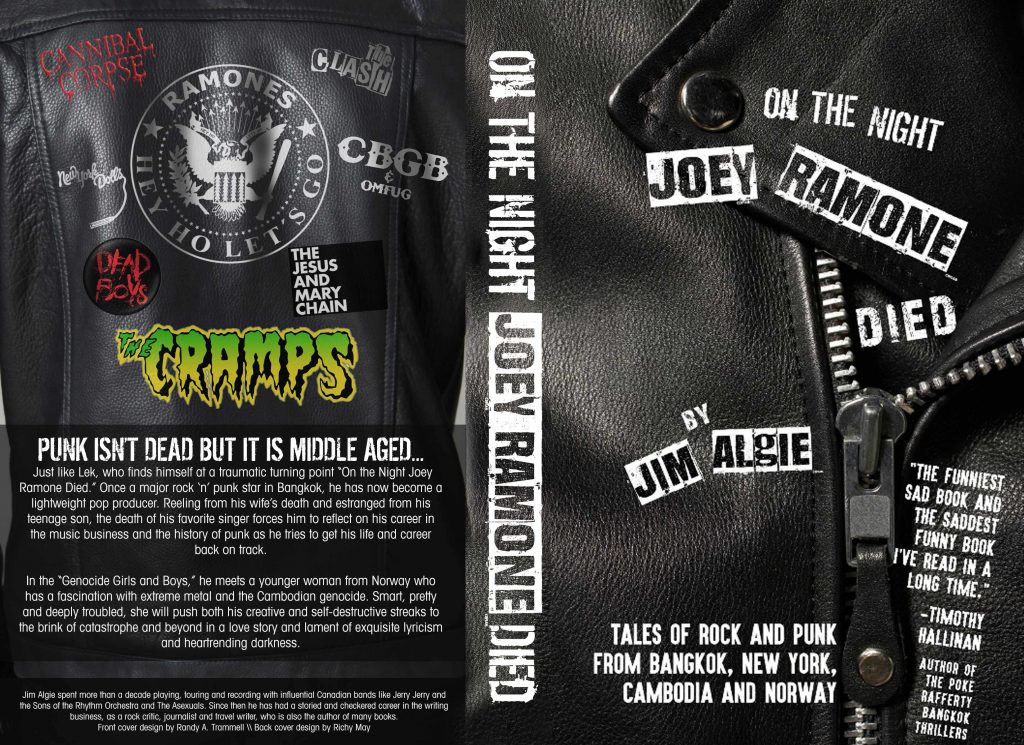

Jim Algie’s latest book, “On the Night Joey Ramone Died: Tales of rock and punk from Bangkok, New York, Cambodia and Norway” riffs on the author’s personal experiences like these in a medley of literature, music journalism, punk history and debauchery. The first paperback edition of the book, released in February 2018, contains a new, 130-page nonfiction section of “Rock Writings and Musical Memoirs” that riffs on the author’s “Close Encounters with Rock Stars” such as Joe Strummer, the Pixies, Ice-T, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Jim Carroll and the Jesus and Mary Chain, while “My Last Gig and Worst Onstage Disaster” chronicles a near-death experience he had in Berlin. The new paperback is available from Amazon for US$12.99.

Revised cover and back covers of the paperback edition of On the Night Joey Ramone Died

Great story, would love ot have seen at least one of the video’s but maybe it’s more rock’n’roll that I can’t hahaha.

It’s probably better that you can’t see them.

Yeah, definitely.